Brahmanism (also known as Vedic Religion) is the belief system that developed from the Vedas during the Late Vedic Period (c. 1100-500 BCE) originating in the Indus Valley Civilization after the Indo-Aryan Migration c. 2000-1500 BCE. It claims the supreme being is Brahman, and its tenets influenced the development of Hinduism.

The Vedas were understood as the eternal words of the universe which had always existed and were not revealed to any one individual but "heard" by sages in meditative states. The being that spoke these words was the creator of the universe and the Universe itself – Brahman – and the Vedas were recognized as defining the Sanatan Dharma ("Eternal Order") which Brahman had established. Belief in the authority of the Vedas was encouraged by the priestly upper class – Brahmins – who could read Sanskrit, the language of the Vedas, whereas the lower classes could not. The Brahmins’ unique position further enhanced their reputation but, eventually, brought about calls for reformation as people objected to this one class dictating religious precepts for all.

Brahmanism’s reforms led to the development of Hinduism (known to adherents as Sanatan Dharma) while those who rejected Brahmanism, and so also Hinduism, formed their own philosophical and religious sects of which Charvaka, Jainism, and Buddhism became the most well-established. Brahmanism continued to exert considerable influence in Hinduism and continues to do so in the present day. Since the mid-20th century, reformers in India, and elsewhere, have opposed Brahmanism as encouraging inequality and brutalization of the lower classes by emphasizing the elite position of Brahmins and helping to maintain the caste system.

Origin & the Vedas

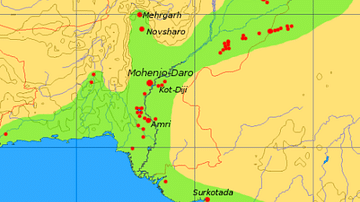

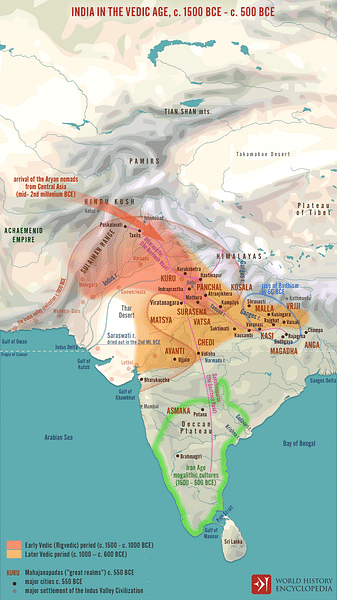

The date and place of origin for Vedic thought is unknown, but two theories have been advanced: the Indo-Aryan Migration theory and the Out of India Theory (OIT). The Indo-Aryan Migration theory suggests that the Vedic vision developed in Central Asia (around the region of the Kingdom of Mitanni, modern-day northern Iraq, Syria, and Turkey) and arrived in India during the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 7000 - c. 600 BCE) sometime between c. 2000-1500 BCE. The OIT claims the Indus Valley Civilization (also known as the Harappan Civilization) developed the Vedic vision, exported it to Central Asia, and watched it return with the Indo-Aryan Migration. The OIT is generally dismissed as lacking substantial evidence and essentially agreeing with the Indo-Aryan Migration theory that the belief structure developed in Central Asia.

A number of gods’ names – notably Indra – were known in Central Asia, and one of the most important concepts of Brahmanism, rita ("cosmic order") was also well established there. It is thought that, sometime around the 3rd millennium BCE, a group of nomadic Aryan tribes migrated into Central Asia and two of these, now known as Indo-Iranians and Indo-Aryans, parted ways; the Indo-Iranians settling the Iranian Plateau and the Indo-Aryans continuing south to the Indian subcontinent. The term Aryan was understood as a class of people meaning "free" or "noble" and had nothing to do with race. The association of Aryan with light-skinned races was only made in the 18th and 19th centuries CE by historians with a racialized worldview.

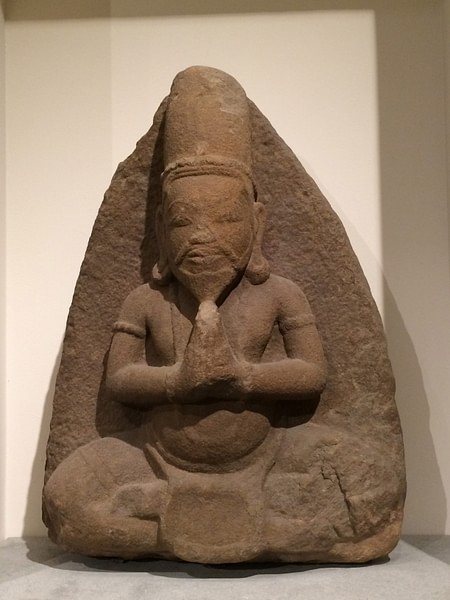

The Indus Valley Civilization was among the most advanced of the ancient world and clearly had some form of religious observance but, because their script remains undeciphered, no one knows what that might have been. Statuary and seals suggest they worshiped spirits known as yakshas which had to be placated and honored through sacrifices and some sort of observance. The yaksha cults seem to have focused solely on the day-to-day needs of the people without addressing cosmological questions. Discussions of the origin of the universe and the meaning of life only arose – as far as the present extant evidence shows at least – with the development of Vedic thought, which may have merged with the yaksha rituals.

The contents of the Vedas were passed down orally from teacher to master until the Vedic Period (c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE) when they were written down. They consist of four texts:

- Rig Veda

- Sama Veda

- Yajur Veda

- Atharva Veda

Each text is individually divided into subtexts:

- Aranyakas – rituals and observances

- Brahmanas – commentaries on rituals

- Samhitas – benedictions and prayers

- Upanishads – philosophical narratives and dialogues

These texts define the Vedic vision which is at the heart of Brahmanism.

Precepts of Brahmanism

The Indo-Aryans are also known as the Vedic peoples, who wrote in Sanskrit and whose religious and cosmographical vision is thought to have merged with that of the Indus Valley Civilization. The Vedas moved the peoples’ relationship with the supernatural from the day-to-day rituals of honoring spirits in a quid pro quo kind of contract to understanding the origin of all existence and the meaning of one’s life. Vedism – the attempt at answering the deepest questions of existence – became Brahmanism once a First Cause was identified.

The Vedic sages recognized that the world operated according to rules that suggested order and the Vedas attributed this order to many gods who, generally, reflected human characteristics. The rules were defined as rita, and their existence implied a rule-maker, but one greater than the gods described in the texts, a god-behind-the-gods who informed them; this god was Brahman.

Brahman was understood as an individual entity but so immensely powerful that the human mind could not comprehend it. This being existed in reality (it could be apprehended), outside of reality (in the realm of pre-existence), and was reality all at once. Brahman had always existed and would always exist but was far too immense for a human being to connect with. The gods of the Vedic pantheon were avatars of this being, but in order to have a personal connection, there had to be some aspect of the human constitution that would allow for it.

It was not thought possible that the source of all life would create life without also providing for a way to commune with it. The human being was understood to be made up of a body, soul, and mind, but to these the Vedic sages added an "oversoul" – the Atman – that allows connection with Brahman because it is a part of Brahman. Every human being was understood to be carrying this spark of the divine within them, and all one had to do was recognize this and devote oneself to nurturing it in order to find peace and comfort in the presence of the divine.

Just as each individual carried this divine spark, so too the many gods were all Brahman’s different aspects, each one tending to a specific human need but all of one indivisible essence. Scholar John M. Koller elaborates:

[The Vedic sages] all recognized that Brahman, as the ultimate reality, could not be defined in any literal way. It could be approached conceptually by describing it in terms of the most perfect qualities conceivable. But since Brahman is beyond conception, ultimately even these highest qualities – being, knowledge, and bliss – must be denied. This is the famous via negativa, characterized in the Indian tradition as neti, neti, an expression that means, literally, "not thus, not thus". Neti, neti clearly reveals the philosophical understanding that Brahman could not be comprehended in conceptual terms.

Reality can be approached in nonconceptual ways, however. Indian thinkers thought of Brahman in personal, as well as conceptual, terms, making use of a great deal of sensual imagery in the process. The senses stimulate feelings and faith as well as thoughts, and India has prized this religious understanding as highly as the understanding achieved through abstract thought. This religious understanding is active, leading a person to embrace or avoid reality in its immediate, concrete forms. With this approach, the knowledge, bliss, and being that describe Brahman abstractly take on flesh and personality as gods and goddesses who can be loved and feared, seen, and touched. In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, who appears as Arjuna’s chariot driver, declares that he is, indeed, the ultimate Brahman. (158-159)

Gods and goddesses with human form and characteristics – even if sometimes depicted with a few extra arms or legs or the head of an elephant – were more relatable than a cosmic force. The priestly class (Brahmins) encouraged the people to embrace their deity of choice as all were equally aspects of the First Cause and Ultimate Reality. The chants, hymns, prayers, and mantras of the Vedas were recited by the Brahmins at ritual observances to assure the people that they already had the divine within them, that their lives and how they lived them needed to be in accord with cosmic order, and that such order did, in fact, exist even if they could not understand how it worked.

Brahmanism & Hinduism

Neither the priests who recited the Vedas nor those who heard them referred to this belief system as Brahmanism. The term 'Brahmanism' was only coined by European scholars in the 16th century CE and came to be used interchangeably with Hinduism. When one claims that Brahmanism became Hinduism, one is remarking on significant developments in the details of the belief system, not the underlying form, which was known to the ancient priests and people, as it is by adherents today, as Sanatan Dharma. The universe was understood as having been ordered for a purpose by a divine intelligence, and each individual had a part to play in that purpose. Hinduism developed the particulars of how a person was to play their part.

As Koller notes above, active religious understanding can encourage one to embrace or distance themselves from reality depending on how they perceive it. The world can be a frightening place of uncertainty or an ordered realm of ultimate meaning, and Hinduism recognized this in allowing for enlightened detachment from the things of life while also encouraging adherents to participate in all aspects fully as gifts from Brahman. An adherent was, and is, expected to focus on life goals (purusharthas) which take three forms:

- Artha – one’s home life, career, and material wealth

- Kama – love, sensuality, sexuality, physical pleasure

- Moksha – enlightenment, liberation, freedom through self-actualization

Each of these is understood as temporal pleasures, but as they are all given by the divine, their value should be recognized. Everyone would eventually die, but while one lived, one’s life goals needed to be attended to through one’s karma (action) performed in accordance with one’s dharma (duty). Each individual was given a duty to perform at birth, something no one else could accomplish, and if they failed to do so as they should in one life, they would be reincarnated to return to earth in the cycle of rebirth and death and try again.

This cycle of rebirth and death was known as samsara – usually translated to mean a child’s game – in which one repeats existence numerous times until one finally understands and performs one’s karma in accordance with one’s dharma, fully connects with one’s Atman, and is freed from samsara. This view was understood as a complete vision of the creation of the universe and explanation for the meaning of an individual’s life, but around 600 BCE a number of reformers rejected the authority of the Vedas to form their own schools of thought with their own vision of reality.

Brahmanism & the Nastika Schools

The concept of samsara suggested a hierarchy, which is explained by Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita (composed c. 5th-2nd centuries BCE) when he is telling Arjuna about the three gunas – states of being that exist in every individual and either help or hinder one’s spiritual awareness and growth – and moves on to discuss the importance of dharma. Part of the Eternal Order, Krishna says, is the caste system (the varnas), which makes clear one’s dharma. The four varnas are:

- Brahmana varna – the highest caste of priests, intellectuals, and teachers

- Kshatriya varna – warriors, protectors, guardians, police

- Vaishya varna – merchants, bankers, clerks, farmers

- Shudra varna – the lowest caste of unskilled workers, laborers, servants

Below the Shudras are the Dalits, often referenced as the untouchables, who are considered ritually unclean and are not included in the varna system.

The Vedas were understood to support the varna system, and as the Vedas were recognized as the word of the Creator, they were not to be challenged. Around 600 BCE, however, thinkers began to object to the authoritative nature of the priests who were able to interpret the Vedas however they wanted since the people could not read or understand Sanskrit. According to tradition, the words of Brahman had been spoken in Sanskrit and recorded as they were "heard" and so the people routinely listened to the priests chanting at them in a foreign tongue which only the Brahmins could interpret for them.

This situation eventually led to a break in Hinduism where people took sides for and against accepting the authority of the Vedas and their priests. Those schools of thought that acknowledged the Vedas were known as astika ("there exists"), while those who rejected the Vedic vision were known as nastika (there does not exist"). The stand on what does or does not exist refers to the authority of the Vedas. There seems to have been many different schools of thought vying for adherents at this time, but the three most prominent were Charvaka, Jainism, and Buddhism.

Of these three, only Jainism posed a serious threat to the authority of Hinduism. Charvaka was a materialist school that focused on life’s pleasures and denied survival of bodily death. A philosophical system that offered no hope for an afterlife was unlikely to gain many adherents, and Charvaka died out. Buddhism, though popular in some areas of India, struggled to find an audience while contending with Hinduism, and Jainism and did itself no favors by fracturing into different schools with divergent expectations for believers.

Buddhism did not gain widespread popularity until the reign of Ashoka the Great (268-232 BCE), who embraced the system and encouraged others to do the same, but even then, it became more popular outside of India. Jainism rejected the concept of Brahman or any creator god, though kept a belief in supernatural beings (devas), the importance of karma, and the cycle of rebirth and death. Jainism’s adherence to The Five Vows and 14 Steps provided a clear path for adherents while eliminating the authoritarian aspect of Hinduism, avoiding the contentions that came to mark the different Buddhist schools, and rejecting the materialism of Charvaka.

Conclusion

Even so, Hinduism survived the challenge of the other philosophical systems because monarchs recognized the value of a divinely ordained caste system in keeping order as well as the kind of pageantry and grandeur the vision of Brahmanism offered. On a purely pragmatic level, the concept of a divine being that made itself accessible through multiple other deities, each one requiring a festival in his or her honor, meant the people could be entertained by a number of celebrations throughout the year. Brahmanism’s vision, developed by Hinduism, encouraged one to do one’s best in accordance with one’s divinely appointed duty and so be content with one’s lot in life, as it was understood as the direct result of one’s actions in a previous lifetime.

Initially, however, Brahmanism did not develop to control people but to answer their questions regarding the origin of the universe and their place in it. The Vedas addressed these questions directly and Brahmanism developed that vision to help people make sense of what can often seem a disordered and chaotic world of random events signifying nothing.

Since the mid-20th century, efforts have been made by reformers to dismantle aspects of Brahmanism – particularly the elite status of the Brahmins – in the interests of equality and fraternity. The reformer B. R. Ambedkar (l. 1891-1956) campaigned against the kind of discrimination against the Dalits that elevation of the Brahmins encouraged, and efforts have been ongoing, sporadically, since his time to level the playing field for all people to have equal opportunity in life. Interestingly, it seems this was the original vision of Brahmanism in establishing that there was a divine being who cared for everyone equally and so deeply that it placed a spark of itself inside of each of them.