Marcus Furius Camillus (c. 445/446-365 BCE) was the first great general of the Roman Republic to also prove himself an able administrator and honorable politician. He was chosen as dictator five times, celebrated four triumphs, and was hailed as the “Second Founder of Rome” and a “Second Romulus” for defeating the Gallic Senone tribe under Brennus in 390 BCE following their sack of Rome.

Camillus' story comes primarily from the Roman historians Livy (59 BCE-17 CE) and Plutarch (45-50-120-125 CE), both of whom clearly admire him greatly, and early modern scholarship dismissed their accounts as largely biased and exaggerated. This conclusion was reached not only because of the obvious high regard they have for Camillus but because they were writing long after his death, using materials no longer extant, and so their accounts were considered unreliable. Further, both accounts give a description of the destruction of Rome which was considered inconsistent with the archaeological evidence.

Recent scholarship has reversed this trend, however, and Camillus' achievements as recorded by both Livy and Plutarch are now accepted as accurate. This is because of archaeological excavations which corroborate them, especially those at the ruins of the Etruscan city of Veii, and a revised understanding of what Livy and Plutarch meant in detailing the devastation of Rome by the Senones: that the city itself may not have been completely destroyed but the people's sense of security and peace had been shattered and was only restored by Camillus.

Camillus is depicted as a man who consistently saw what needed to be done and had the strength and resolve to do it. His engagements with Rome's adversaries were uniformly successful and his administrative and diplomatic skills were equally impressive. Even so, his political enemies routinely contrived against him and the people themselves were unappreciative of his talents. He left Rome voluntarily for the city of Ardea when he was unjustly charged with theft. When the Senone tribe sacked Rome, however, Camillus returned from exile, defeated them, and was hailed as the city's savior. He died of the plague in 365 BCE.

Early Life & Rise to Power

Camillus was born c. 445/446 BCE to the patrician family of the Furii Camilli of the city of Tusculum. His father was the tribune Lucius Furius Medullinus and he had two brothers, Lucius and Spurius, both of whom also had illustrious careers. Camillus was the youngest and was given his surname because a camillus was a noble youth who served as an assistant to a priest. It is likely that Camillus held this position in service to his relative Quintus Furius Paculus who was high priest of Rome at this time.

Camillus quickly distinguished himself in military service in the wars against the Aequians and Volscians under the leadership of the dictator Postumius Tubertus. Plutarch describes his courage in battle:

Dashing out on his horse in front of the army, he did not abate his speed when he got a wound in the thigh but, dragging the missile along with him in its wound, he engaged the bravest of the enemy and put them to flight. For this exploit, among other honours bestowed upon him, he was appointed censor, in those days an office of great dignity. (Life of Camillus II.1-2)

Following his military success, he proved his administrative competence through an initiative whereby single men in Rome would be married to widows of veterans of the wars. This would create stable households and provide for the widows without the state having to do so. He also reformed taxation so that orphans of the wars were given jobs which could now be taxed whereas, before, they had been exempt. As Plutarch points out, the wars at this time were incessant and costly and any means of raising funds was considered worthwhile. Rome had been at war with various cities and tribal communities for years but easily the costliest was their conflict with the city of Veii.

The Siege of Veii

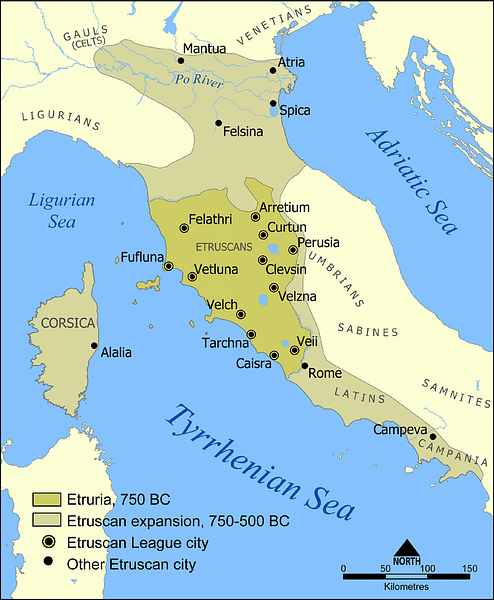

Veii was a wealthy Etruscan town and a rival of Rome, having steadily gained in power and prominence throughout the 6th century BCE. The city was a member of the confederacy known as the Etruscan League which linked 12 or 15 Etruscan towns in a loose alliance. Veii's rivalry with Rome, however, seems to have been considered its own affair since there is no evidence that the other towns in the league became involved in the conflict.

Throughout the 5th century BCE, Veii's wealth declined as trade was increasingly siphoned away by Syracuse. Although it was still an affluent city, its strength may have seemed diminished to the Romans who decided to resolve tensions by attacking in 406 BCE. Veii was far from vulnerable, however, as it was heavily fortified and defended by thick walls, necessitating a siege which would last ten years.

Camillus had been in command of the army for some years by this time, fighting against the cities of Capena and Falerii which were allied with Veii, but was now named dictator and given the responsibility for ending the unpopular war. He defeated the forces of Capena and Falerii and looted Capena. He was then able to turn his full attention to Veii itself.

Camillus captured a citizen of the city, who was lured out beyond the gates by one of the Roman soldiers, and learned that the earth was soft beneath the city's walls and one could tunnel into the citadel without much effort. Camillus then launched an attack on the front gates to hold his opponent's attention while he sent engineers to dig beneath the walls. The plan was a success as the Roman soldiers emerged in the citadel, engaged the defenders, flung open the gates, and Veii was sacked.

Camillus had the statue of the city's patroness, Juno, removed and brought to Rome and allowed his soldiers to keep whatever plunder they had taken. The women and children of Veii were sold as slaves while most of the males were executed. At this point, although he had ended the war and enriched Rome, Camillus fell out of favor with the people through the extravagance of his Roman triumph which they felt was arrogant and vain in that it clearly mirrored festivals associated with the gods (Life of Camillus VII.1-2).

The people were also frustrated by his refusal to allow Roman citizens to populate Veii. Rome was overpopulated and a plan had been proposed to relocate some citizens to Veii. This proposal was quite attractive since there were arable lands around the city and, after its defeat, plenty of empty homes and buildings. Camillus rejected the plan, however, claiming it would only weaken Rome, and then constantly diverted the people's attention with other matters in hopes that they would forget about Veii.

Veii continued to be a sore spot for him, however, as there was another problem the people – especially his soldiers – would not forget. When he initiated his campaign against Veii, he had sent to the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi for advice and had promised one-tenth of the spoils of the city to the Delphian god. Following his victory, however, he forgot his vow. The priests of Rome claimed the gods were angry because the vow had not been kept and Camillus tasked his soldiers with returning their spoils but this was difficult, if not impossible, for them to do since many had already spent or distributed what they had taken. They felt that it was Camillus who had made the vow and it was Camillus who should pay but he had no intention of doing so. Finally, the women of the city offered their gold jewelry to be melted down into a bowl for the gods and so resolved the issue but Camillus' reputation suffered as a result of the incident.

The people again pressured him to ratify the proposal for relocating half of the population to Veii and Camillus again sought ways to divert their attention. It happened, to his good fortune, that Falerii asserted itself and he had to mobilize the army to attack the city in a preemptive strike. This action successfully distracted the people and turned the enmity they felt for Camillus toward the Falerians.

The Falerian School Master & Exile

Falerii's walls were strong and well defended, however, and so another siege was initiated which looked as though it could be quite lengthy. Plutarch notes that the Falerians were so unconcerned about the siege that they went about their daily business in the city as though the Romans were not even there outside the walls. The siege must have disrupted the lives of the citizens to some degree, however, because one of them decided on a drastic means of bringing it to an end.

The sons of the nobles of the city were all entrusted to the tutelage of a single school master so that they would develop close bonds with each other as they grew up. Every day the school master would lead these boys outside the city walls for their exercise and, each day, he led them further and further. Finally, he brought them to the Roman sentries, handed them over, and demanded they be brought to Camillus to be ransomed back to the city and so end the siege. The sentries brought the boys and their teacher to the general and Plutarch describes Camillus' response:

It seemed to Camillus, on hearing him, that the man had done a monstrous deed, and turning to the bystanders he said: "War is indeed a grievous thing and is waged with much injustice and violence; but even war has certain laws which good and brave men will respect, and we must not so hotly pursue victory as not to flee the favours of base and impious doers. The great general will wage war relying on his own native valour, not on the baseness of other men." Then he ordered his attendants to tear the man's clothing from him, tie his arms behind his back, and put rods and scourges in the hands of the boys, that they might chastise the traitor and drive him back into the city. (Life of Camillus X.3-4)

The Falerians, meanwhile, had become alarmed to find the school master missing with all the noble sons of the city and had begun searching everywhere when they saw the boys returning across the fields beating the bound teacher. The boys praised Camillus' valor and called him their savior and father and the elders of the city, suitably impressed, surrendered and placed themselves at the mercy of the general. Camillus was pleased with the outcome and sent the Falerian emissaries on to Rome to finalize the surrender but his men were far from satisfied. They had been counting on the plunder from the sack of the city and, when it was clear that would not happen, they turned on their commander.

The resentment over the plunder from Veii had not diminished and now there was this new incident which the soldiers interpreted as a show of disrespect towards them by Camillus. They claimed he had no regard for the common people and was only interested in his own glory and supporting the upper class. Further, the proposal of sending half the population of Rome to settle Veii again arose and, again, Camillus refused to support it and this led to greater animosity among the people. His political enemies seized on the moment and charged him with theft of plunder from Veii which they claimed should have gone to the Roman people. A large fine was proposed which his friends offered to pay on his behalf but Camillus refused to recognize the false charges and chose instead to exile himself to the town of Ardea. He is said to have paused outside Rome's gates as he left and prayed that the people would repent and realize how much they needed him; if so, his prayers were answered not long after in the form of the Senones from Gaul.

The Battle of Allia & Sack of Rome

The Senone tribe had been in Italy since the early 4th century BCE and had served as mercenaries for various towns and cities in their wars with each other. In c. 391 BCE they arrived at the city of Clusium under the leadership of their war-chief Brennus either as a mercenary band serving one political faction of the city against another or simply looking for a new home (both versions of the story are equally probable). The Clusians asked them to move on and the Senones lay siege to the city so Clusium appealed to Rome for help.

The Roman ambassadors who arrived to resolve the conflict took up arms in Clusium's defense, however, which enraged Brennus and his men as this was dishonorable and contrary to the accepted rules of war. Brennus called off the siege of Clusium and marched on Rome. The Romans thought so little of this barbarian army that they not only failed to make the proper sacrifices to the gods but also took little care in mobilizing and arranging their army for defense. Brennus defeated them easily at the Battle of Allia in 390 BCE.

Survivors fled back to Rome with the news and the citizens evacuated the city except for the senators and a small band of defenders who took up positions on the Capitoline Hill. When Brennus and his army arrived, they found the city empty and began sacking it until they discovered the fortified hill top and then settled in for a siege. Food was scarce and so Brennus sent out armed groups to raid nearby towns and one of these was Ardea where Camillus was living. He appealed to the elders of the town to allow him to rally and lead a force against the Senone raiding party and, this granted, he came upon their camp by night and killed almost all of them.

When the Roman refugees in other towns heard of his victory they begged him to take command of what was left of the Roman army and drive the invaders from their city but Camillus said he could not do so without the consent of the defenders of Rome because, otherwise, he would be marching an armed force against his own city. Acquiring this consent was only possible by sending a volunteer by night into Rome to scale the hill, deliver the proposal, and return with an answer but, in doing so, the soldier disturbed some rocks and turf in his climb which the Senones noted the next morning. They realized they had been shown a way to come up behind the defenders and launched an early assault. They were defeated but, by now, the food supplies of the Roman defenders were almost gone and they were forced to seek terms.

Camillus entered the city just as Brennus and the Romans were about to conclude the treaty and declared it invalid because only he could authorize such a contract and was not about to do so. The Romans and Senones then fought in the streets until Brennus withdrew to better ground for his troops outside the city walls but this did him no good; Camillus pursued them and was victorious. It is assumed that Brennus was killed in the battle as he is not referenced again. Camillus was praised as a second founder of Rome and was reinstated with all honors as dictator.

Later Campaigns & Death

Following his victory, Camillus decreed the reconstruction of Rome. The proposal to relocate part of the population to Veii had again come before the legislators and Camillus again rejected it on the same grounds he had before: that it would only weaken the city. This time, the citizens accepted his arguments and the proposal was finally dropped.

While Rome was rebuilding, the Volsci and Aequi invaded the region, thinking the Romans easy prey, and Camillus led his armies to victory against both. He also defeated the Etruscans who had taken the nearby city of Satricum. He was Consular Tribune in 384 and 381 BCE when, although in poor health and longing to retire from public life, he again led Roman forces into battle against the Volsci and was again victorious. He was named dictator once more in 368 and 367 BCE although, again, he would have preferred to retire and also defeated the Gauls at the Battle of the Anio River in 367 BCE.

The long, lingering charge against him that he favored his own upper class at the expense of the poor was finally put to rest when he passed the laws known as the Lex Licinia Sextia in 367 BCE which limited interest rates on loans and restricted private ownership of land; both stipulations favored the lower classes. Camillus was still in office in 365 BCE, working for the people of Rome, when the plague struck the city and he was among its victims.

In the present day, Camillus is rarely featured on lists of great Roman generals and is often overlooked in articles discussing Roman dictators, which usually focus on figures like Sulla and Julius Caesar, but he was among the greatest military leaders and politicians Rome ever produced. Although mistreated by his countrymen, and almost constantly under attack by political rivals, Camillus consistently put the good of his city before his own interests and was praised for generations after his death as a “second Romulus” and savior of Rome.