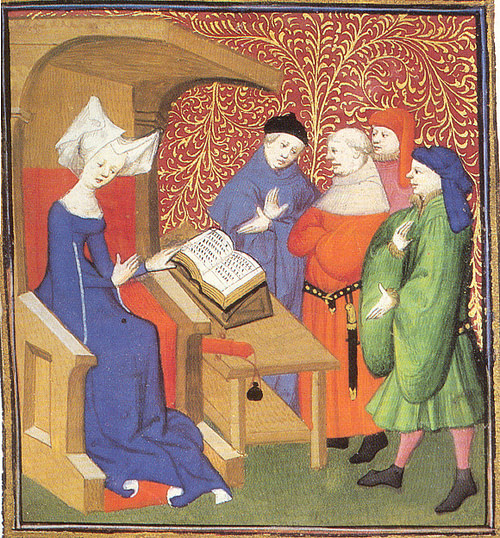

Christine de Pizan (also given as Christine de Pisan, l. 1364 - c. 1430) was the first female professional writer of the Middle Ages and the first woman of letters in France. Her best-known works advocated for greater equality and respect for women, anticipating the feminist movement of the 19th century by 600 years.

She was born in Venice, Italy but her family soon moved to France when her father was appointed astrologer to the court of the French king Charles V (r. 1364-1380). Although she always valued her Italian heritage, she was devoted to France and the royal court throughout the rest of her life.

She was widowed when her husband died of the plague in 1389, leaving her with three children and the responsibility of caring for her mother and niece. With no other options open to her to earn a living, Christine took to writing. She penned romantic ballads for the French aristocracy which were so well-received she pursued writing as a career. Among her best-known works are:

- One Hundred Ballads (1393)

- Moral Lessons (1395)

- Letter of the God of Love (1399)

- Letter of Othea to Hector (1399)

- The Tale of the Rose (1402)

- On the Mutability of Fortune (1403)

- The Book of the City of Ladies (1405)

- The Treasure of the City of Ladies (1405)

- The Book of Feats of Arms and Chivalry (1410)

- The Book of Peace (1413)

- The Tale of Joan of Arc (1429)

Although modern-day scholars continue to debate whether she can be called a “feminist” when the concept did not exist in her lifetime, there is no denying that she embodied the values and principles of feminism, specifically that women were the equals of men in every regard and should be accorded the same rights, opportunities, and respect as any male. Her works would influence later writers, male and female, through the early era of the Renaissance after which they fell out of favor and were only rediscovered in the late 19th century.

Early Life & Marriage

Christine was born in Venice, Italy, the daughter of the scholar, physician, and astrologer Thomas de Pizan, who encouraged her education. Her mother's name is unknown but she was an aristocratic woman of the Mondino family of Venice, and the couple had three children; two boys and a girl. The family moved to Paris, France, when Christine was four years old and her father was appointed court astrologer.

Christine was drawn to literary pursuits at an early age but was discouraged by her mother who felt she should remember her place and concentrate on 'women's work' such as spinning cloth and tending to domestic chores. Scholar Charity Cannon Willard notes, “It is evident that her mother won her point because Christine explained that she had been obliged to gather up such crumbs of knowledge as she could from her father's wisdom” (33). Little mention is made of Christine's mother in her later works other than that she required care and lived with the author.

Thomas de Pizan, on the other hand, is referenced in Christine's writing and evidently did what he could to support his daughter's education. The family lived on the right bank of the River Seine near to the heart of the city's book-making industry. Christine grew up in the palace of Charles V – well known for its library – and in proximity to the scribes, copyists, illustrators, and illuminators who produced the books of the day.

She was married at the age of 15 to the court secretary Etienne du Castel in 1379, and the couple would have three children (one of whom died young). They had a happy marriage, and there is no indication at this time that Christine wanted to be doing anything other than be Etienne's wife and raise their children. The fortunes of the family turned dramatically, however, when Thomas de Pizan died in 1388 and Etienne died of plague the following year. After ten years of marriage and 25 years of a stable, upper-class life, Christine was suddenly alone and responsible for the care of her three children, her niece, and her mother.

Early Poetry

With no knowledge of how her husband was paid or even what he earned, Christine attempted to negotiate with the French bureaucracy for his final salary and a bonus he was due but she lacked any experience in handling such a situation. Her husband had died while on a job for the king in another city, and this complicated matters further in that he would have been paid differently for that kind of service as opposed to his regular duties in Paris.

The corruption of the government officials she was dealing with certainly played a part but the central obstacle to her recovering Etienne's salary was that she was a woman and, as such, had been denied the opportunity to learn anything of her husband's business or finances. She seems to have been regularly dismissed by the government clerks she spoke with and would spend the next 13 years struggling with lawsuits in an attempt to win what was rightfully hers or protect what she had left from creditors.

She began writing poetry, as she says, to distract her mind from her troubles and seems to have survived by selling off land. Her two brothers had returned to Italy to take over land owned by their father and could not help her other than perhaps by brokering the deal for the land she sold in Italy. Christine would later complain in her writings that she “had not been able to spend her early years learning what would have been useful to her later on, particularly how to look after her husband's financial affairs after his death” (Willard, 33). She at first had no thought of pursuing a literary career to support herself and her family; she was only writing poetry to make herself feel better.

Christine read widely prior to her husband's death, beginning with ancient history, working her way up to her present era, and then starting in another discipline such as the sciences or philosophy. After his death, she continued her self-education although modern-day scholars are at a loss to explain where she would have gotten books from. It is probable – almost certain – however, that she continued to have access to the court library as many of her early poems are addressed to members of the royal court and she is on record as the court writer.

As Christine herself writes, she studied each subject diligently and in detail in pursuit of intellectual power but, when she reached poetry, she felt in her heart that this was her life's calling. Poetry spoke to her and she responded to the inspiration by speaking back. By 1393, she had enough poetry completed to publish her first book, One Hundred Ballads, which she presented to the court. The French court appreciated her work and she was encouraged to write more through their financial patronage and so began her literary career.

Literary Career & Major Works

Christine's early poetry almost always features a young female narrator who is either in love or mourning the loss of her lover. These themes were already established motifs of the French troubadours of the 12th century and were at the heart of the literary tradition of courtly love. Poetry celebrating the concept of courtly love commonly featured a woman so beautiful, mysterious, virtuous, and kind that she casts a spell over the knight who must serve and protect her but also often cast these women as temptresses who destroyed a knight's virtue. Christine's poetry often picks up on these themes but presents them on a more personal level and attempts to remove the misogynistic elements of the genre.

An example of her vision is seen in one of her best-known early works, “Alone am I, alone I wish to be” in which the speaker meditates on the loss of her lover and how lonely she is – “more lost than anyone” – but at the same time asserts that she would not change her situation and has no need of rescue by any “knight”. Each stanza ends with the line, “Alone am I, left without a lover” but the speaker repeatedly is only stating facts about her condition and how she feels about it; there is nothing in the poem indicating she wishes to do anything to change it, as in the lines:

Alone am I, to feed myself with weeping

Alone am I, suffering or at rest

Alone am I, and this pleases me the best (Willard, 54)

Courtly love poems featuring the damsel-in-distress motif were quite popular with the French court, as Christine must have known, and works like “Alone am I” established her as a new voice in French letters and one people paid attention to for her departure from the central conceit of the genre. In “Alone am I”, it is clear the speaker is not seeking another lover and will endure her loss on her own through her own strength and resolve.

In 1399 she published her bestseller Letter of Othea to Hector in which the legendary hero Hector of Troy is taught lessons in government and virtue by the goddess Othea. The same year she published another of her great works, Letter of the God of Love (also known as Cupid's Letter) in which the narrator appears as a secretary in the Court of Love and reads a letter from the lord and god of the court, Cupid. This work picks up on a number of themes from courtly love literature, satirizes the inherent misogyny of the genre which so often portrays women as weak and in need of rescue or as wicked seducers, and emphasizes how poorly men treat women and how the god of love wants that to change. Taking that challenge upon herself, in 1402 Christine published her Tale of the Rose, a critique of the bestselling poetic work, The Romance of the Rose by Jean de Meun.

The Romance of the Rose is an allegorical poem detailing how a lover should woo his beloved to win her heart and virginity. The lover enters a garden, must bypass or conquer various obstacles, and is finally able to pluck the rose of his desire. The first part of the poem was composed c. 1230 by the poet Guillaume de Lorris, about whom nothing else is known, and the second by Jean de Meun in c. 1275. Christine found Jean de Meun's section exceptionally misogynistic, and her critique is a refutation of the characterization of women as vile temptresses, seducers, and the source of all evil in the world.

She expanded upon her vision of the true nature of womanhood and the feminine in her two greatest works, The Book of the City of Ladies and The Treasure of the City of the Ladies (also known as The Book of the Three Virtues) in 1405. The Book of the City of Ladies has been hailed as a proto-feminist work, a feminist work, and a masterpiece of feminist literature but, whatever label one chooses to affix to it, it was a revolutionary piece of writing, completely unprecedented, and brilliantly composed. Scholar Jill E. Wagner comments:

Christine anticipated the feminist necessity of Virginia Woolf's “a room of one's own” but she builds on a grand scale and follows medieval tradition in deliberately selecting a city, not a room. While giving voice to the unvoiced, thus presenting her public with provocative new material, she adheres to an established, respectable historical model, St. Augustine's City of God. (69)

The Book of the City of Ladies is an allegory in which three women, Reason, Justice, and Rectitude, build a city with the help of Christine, the narrator. The structure is modeled on Saint Augustine's work but Christine carefully and cleverly employs the memory enhancement technique of the Method of Loci (also known as Memory Palace) by which a person wishing to remember some information pictures it in different rooms of a house or palace. As Wagner points out, by constructing the piece this way, Christine ensured that women of the future would remember the power of women in the past and could draw strength from them.

The Book of the Three Virtues continues this theme as a practical guide for women in taking care of themselves, their homes, and their husband's lands and business affairs. The inspiration for this work was Christine's own feelings of helplessness following her husband's death and her inability to navigate the financial world of men as a new widow. Christine claims that, after writing The Book of the City of the Ladies, all she wanted to do was rest but that Reason, Justice, and Rectitude – who had helped her build the earlier book – would not allow her sleep until she had completed the second work.

In 1410, Christine was commissioned to write a book on the art of war called The Book of Feats of Arms and of Chivalry which described a just war, reasons for waging war, and suggestions on its prevention. This latter point was developed from a section in The Book of Three Virtues in which Christine advised women to try to keep men from making war on their neighbors as it was very costly on every level. She continued this theme in her Book of Peace (1413) which discusses good government, the duty a government owes to its people, and suggestions on preventing armed conflict.

Christine was born during the Hundred Year's War (1337-1453) in which France and England fought for political supremacy over France. In October 1415 the French lost the Battle of Agincourt, and this was such a blow to Christine that she withdrew from society and letters and retired to a convent.

Christine's last work was The Tale of Joan of Arc, written in 1429 in honor of France's great heroine at the height of her popularity. Joan of Arc had just recently lifted the Siege of Orleans (October 1428 - May 1429) and all of France was celebrating the triumph. Christine's poem is the first to celebrate the Maid of Orleans and the only one written in Joan's brief lifetime. A woman leading men into battle, and emerging victorious, must have been a dream come true to Christine who had been advocating for women's equality throughout her adult life. It is probable that Christine did not live to see Joan's capture, imprisonment, and execution as she most likely died sometime in 1430.

Influence & Legacy

Christine de Pizan's works were translated into other languages during her lifetime and her influence was significant. After her death, her books continued in print and were translated further. The influential Anne of Brittany (l. 1477-1514), Duchess of Brittany and Queen Consort of France had Christine's works in her personal library and shared them with friends who then suggested them to others. Christine's works were published by William Caxton (l. 1422-1491) in England, the same man who published Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, Aesop's Fables, and Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur. Her books continued in print and popularity through the early part of the Renaissance when, for unknown reasons, they fell out of print. Christine was rediscovered in the 19th century and has steadily regained a following primarily because of feminist interest in The Book of the City of Ladies and The Treasure of the City of Ladies which are both regularly taught in Women's Studies classes at university.

Although the concepts and values Christine championed may seem common sense and obvious to many – if not most – in the modern day, they were by no means so in the Middle Ages. Christine's works were revolutionary in their time, and one fascinating aspect of her career is how popular her books were, not only in her own country but in others, at a time when the Church – whose values dictated those of society at large – regularly denigrated and demonized women.

Christine herself recognized she lived in 'a bad time' when she and women in general were not appreciated, and yet she was among the most successful professional writers of her era. She was an exception to the rule, however, and the Church and aristocracy would continue their control of and denigration of women as the Middle Ages drew to a close. It would not be until the 19th century that a woman's movement would emerge on the world stage which could even try to embody the vision of Christine de Pizan and gather the kind of support and recognition to bring her dream a little closer to becoming reality.