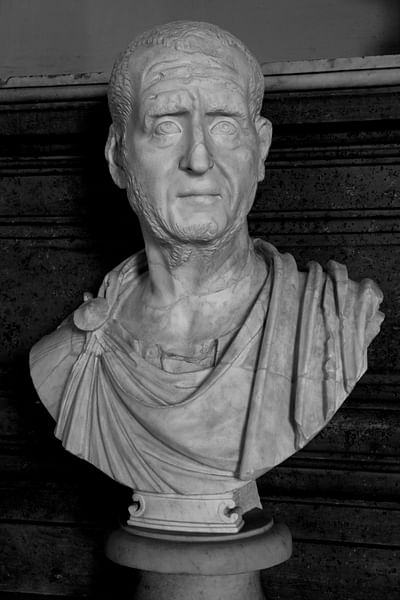

Cniva (also given as Kniva, c. 250 CE to possibly 270 CE) was the king of the Goths who defeated Emperor Decius (249-251 CE) at the Battle of Abritus in 251 CE. Little is known of him other than his campaign in 251 CE, in which he successfully took Philipopolis, killing over 100,000 Roman citizens and enslaving survivors, lay siege to the city of Nicopolis, and defeated the Romans under Decius, killing both the emperor and his son.

Cniva may have learned strategic skills and tactics in the Roman army, as many Goth warriors were enlisted or served as mercenaries, or could have simply had a natural talent for warfare. Either way, he proved a formidable adversary to Rome and defeated their forces so completely that, after the death of Decius, the Romans had no choice but to allow him to safely depart their territory with all the booty and prisoners he had taken from Philipopolis.

Scholar Michael Grant observes that “in Kniva the Goths had a leader of unprecedented caliber, whose large-scale strategy created the gravest perils the empire had yet undergone” (31). Even so, after the campaign of 251 CE, nothing else is heard of Cniva unless one accepts the theory that he is the same person as King Cannabaudes (also given as Cannabas, c. 270 CE) who was killed in battle, along with 5,000 of his troops, in an engagement with Aurelian (270-275 CE).

This engagement was a decisive victory for the Romans, and if one accepts that Cniva and Cannabaudes are the same man, it would explain why Cniva was able to successfully take a walled city through siege while later Goth armies could not: those with the knowledge and skill for siege warfare were killed in 270 CE.

The Crisis of the Third Century

Cniva lived and fought during the period in Roman history known as the Crisis of the Third Century (also the Imperial Crisis, 235-284 CE). This period is marked by almost constant civil war, plague, economic uncertainty, threats of invasion, the breakaway empires under Postumus (260-269 CE) and Zenobia (267-272 CE), and a crumbling and unstable Roman Empire governed by leaders who, for the most part, were more interested in their own personal glory than the good of the state.

The Crisis of the Third Century began with the assassination of the emperor Alexander Severus (222-235 CE). Alexander was controlled by his mother who dictated most, if not all, of his policies, and this proved to be a great liability. On campaign with his troops against the German tribes, Alexander followed his mother's counsel to pay the Germans for peace instead of engaging them in battle. This decision was seen by his troops as dishonorable and cowardly and killed him and his mother, raising the commander Maximinus Thrax (235-238 CE) to replace him.

Between 235-284 CE over 20 emperors would come and go, some quite quickly, as compared with the 26 who reigned from 27 BCE - 235 CE. These rulers are now referred to as the “barracks emperors” because they were supported by and largely came from the army. The emperor of Rome had always relied on the support of the military to one degree or another but now such support became vital to an emperor's success and even survival. The difference between these emperors and those who came before – and after – was that they were largely motivated by personal ambition and relied on their popularity with the army, and so continued military support, for their authority to rule.

During the Crisis of the Third Century, an emperor's worth was gauged by immediate, discernable, results; a thoughtful or cautious man would not survive in the position any longer than one inept or cowardly, and yet these judgments were entirely subjective. Throughout this period, it is no exaggeration to say that elevating a man to the position of emperor was on par with issuing him a death sentence; if an emperor failed to produce results, he was killed and replaced by another who showed more promise.

Cniva, Decius, & the Fall of Philipopolis

This paradigm was adhered to as Maximinus Thrax was assassinated by his troops in favor of the young emperor Gordian III (238-244 CE) who was possibly assassinated by his successor Philip the Arab (244-249 CE) who was then killed by Decius. In each of these instances, the assassination did not take place in a vacuum nor was it orchestrated by a single man. If an emperor fell out of favor with his troops, he could more or less count on a conspiracy forming which would result in his death.

It was in the midst of this unstable period that Cniva marched into Roman territory in 250 CE at the head of an army comprised of different peoples: the Carpi, Bastarnae, Taifali, Vandals, as well as his own Goths. He first attacked the border city of Novae but was driven back by the general (and future emperor) Gallus (251-253 CE). Cniva moved on and lay siege to the city of Nicopolis ad Istrum while the Carpi contingent of his army attempted to take the city of Marcianopolis. Both of these cities repelled the attacks, thanks to their fortifications, and Decius arrived with his army to relieve the siege of Nicopolis.

Decius had been in the Danube region since 249 CE when he deposed Philip and took over as emperor. He had been kept quite busy with various incursions into Roman territory because Philip had stopped the payments to the Goths, Sassanid Persians, and various other tribes, initiated by Maximinus Thrax, which had kept them at bay (or, at least, not openly hostile). Decius drove Cniva's forces from Nicopolis but did not decisively defeat him. Cniva led his forces north, ravaging the country, and was pursued by Decius.

In the north, near the city of Augusta Traiana, Decius paused to rest his army and was attacked by Cniva's forces. The Romans were taken completely by surprise and suffered severe casualties while Decius and his commanders fled the field with whatever they could gather of their army. Cniva gathered what supplies and weapons were left behind and marched again south toward Philipopolis.

He lay siege to the city in late spring 250 CE while Decius was trying to recover his army. Philipopolis was garrisoned by a Thracian force under the command of Titus Julius Priscus (c. 250 CE) which was far too small to defeat the immense force of the Goths and their confederates outside the walls. The Thracians declared Priscus emperor, perhaps to empower him to legally negotiate with the Goths, and he brokered a deal by which the city and its people would be spared if they surrendered without resistance. Once the gates were open, however, the Goths ignored the agreement, and the city was sacked and burned. Priscus was either killed or captured at this time since he is not heard of in later reports.

The Battle of Abritus

Cniva completely looted the city and took thousands of citizens captive. He turned his forces around and headed back for the borders and his homeland with his treasures while Decius was still recovering his forces. Once finally organized and regrouped, the Roman forces again pursued Cniva's army as it moved north toward the border. Cniva, hearing of the pursuit, halted his retreat from Roman territory and took up position in a marshy area near the city of Abritus, a region he seems to have known well.

The Goth leader divided his forces into a number of different units (sources record at least three and possibly seven separate divisions) around a large swamp. His front line was positioned across the far side of the swamp while he and another unit took position behind it; other units were placed on either side. When Decius heard that the Goths had stopped their march and were encamped, he hurried to the site, arranged his forces, and attacked Cniva's front line; the only opposing force he could see.

The Goths fell back before the Roman forces and took flight through the swamp, drawing Decius and his army after them. The swamp completely nullified any advantages of the Roman formations, and they found themselves trapped and then attacked from three sides by Cniva's army. Decius and his son were both killed and the rest of the army almost annihilated. The commander Gallus, who was now proclaimed emperor, led the remnants of the army out of the swamp and retreated.

Cniva took his men and the booty from Philipopolis and continued on his way home. Gallus has been criticized since for not pursuing the Goths and rescuing the captives, but as scholar Herwig Wolfram points out, he had little choice in the matter:

[Gallus] had to allow the Goths to move on with their rich human and material spoils and even had to promise them annual payments. This is why he is charged to this day with treason and incompetence. But in fact, his actions were forced upon him by circumstances. After the defeats at Deroea and Philippopolis, and especially after the catastrophe at Abritus, the new emperor had no other choice. He had to get rid of the Goths as quickly as possible. (46)

Cniva as Cannabaudes

After Cniva leaves Abritus in 251 CE there is no further news of him. Between c. 253 and 270 CE, however, the Goths were masters of the Danube territories and no Roman emperor could unseat them. They launched ships on the Black Sea and ravaged the coasts as pirates as well as continuing to do as they liked throughout the region. The Battle of Naissus in 268/269 CE was a major Roman victory over the Goths but still did not drive them back from Roman borders.

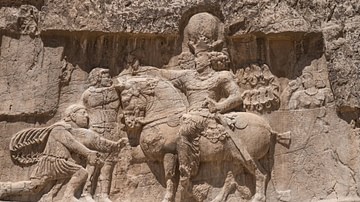

In 270 CE, however, the emperor Aurelian engaged a large force of Goths under a king whose name is given in the Historia Augusta as Cannabaudes/Cannabas. This was a decisive Roman victory with Goth casualties given at 5,000. Aurelian drove the survivors out of the Balkans and into Dacia, improved the Black Sea defenses and broke Goth power in the region. He then left Dacia to the Goths and returned to his objective of unifying the empire by defeating Zenobia of Palmyra and her powers in the east and then reducing the Gallic Empire under Tetricus I (271-274 CE) in the west.

It would not be impossible for the same man to have led the Goths in 251 CE and in 270 CE, even if Cniva would have been fairly old by that time. The success of the Goths in their engagements with Rome between 251 and c. 269 CE remained consistent until the Battle of Naissus pit the emperor Claudius II (268-270 CE) against a Gothic force led by an unnamed king who could have been Cniva. Claudius II earned the title Claudius Gothicus for his victory, but his success was actually due to the tactics of his cavalry commander Aurelian who, once he became emperor, would use the same tactics effectively against the forces of Palmyra.

Having defeated the Goth forces once under Claudius, Aurelian seems to have had no problem doing so again in 270 CE as emperor, when he killed the king Cannabaudes and 5,000 of his men. After this engagement, the Goths are pushed into Dacia and lose their hold on the territories they had gained since 251 CE. After 270 CE, the Goths pose no great threat to Rome until almost the middle of the next century. It is likely, therefore, that their previous success was due to a powerful king who was skilled in warfare.

One of the most interesting aspects of Cniva's story is his ability to lay siege to Roman cities. Over 100 years later, the Gothic leader Fritigern (c. 380 CE) was unable to take fortified cities because he lacked siege engines and the required skills. Even though Philipopolis was surrendered by the garrison commander, the siege must have been effective enough to warrant that decision.

Since it is clear that Cniva was able to reduce a large city by force – while Fritigern studiously avoided trying to take cities – it must be assumed that these skills were lost between his time and that of Fritigern. It is quite probable, therefore, that Cniva was the Cannabaudes killed in 270 CE along with any of his commanders who would have also had the knowledge and skills conducive to siege warfare.

Regarding this possibility, the scholar Herwig Wolfram writes:

Although in a formal sense we may be dealing with an equation of two unknowns [specifics of Cniva's and Cannabaudes' lives], a hypothetical solution would be as follows: Cniva, a successful Gothic commander and king of the army in the western tribal territory, is killed in battle as Cannabas against Aurelian. With him perish his people, supposedly five thousand men; the kingship is extinguished. (35)

If Cniva were the king of the Goths defeated at Naissus, it would have made Claudius II's victory all the more glorious in avenging the death of Decius and his son at Abritus in 251 CE. It would seem, however, that if that were the case then some mention would be made of the king's identity. As it stands, the king of the Goths at Naissus goes unnamed and Claudius II's great victory is celebrated simply as driving the Goths from the Balkan borders with no addition of avenging Decius. This has led some scholars to conclude that the Goth king at Naissus could not have been Cniva, but it is possible that the Roman writers simply did not know the king's name.

By the time Aurelian's battle with the Goths is recorded the Goth king is known as Cannabaudes/Cannabas and, although some scholars have suggested that this was Cniva's son, there are no ancient accounts to support that claim. Taking into account the loss of military knowledge evident in Goth engagements following Aurelian's victory in 270 CE, the most probable scenario is that it was Cniva himself who finally fell to Aurelian, an adversary who could best even the greatest of warrior-kings.