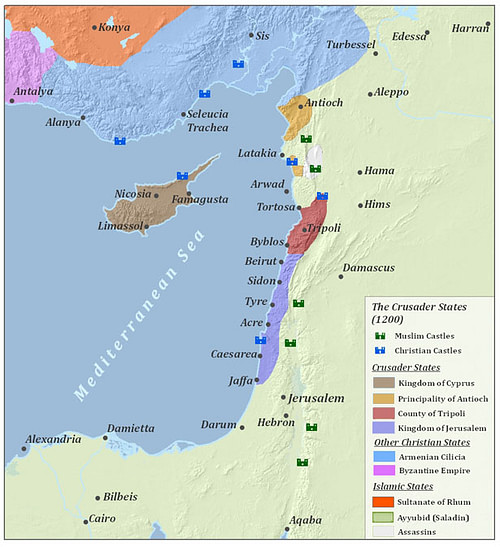

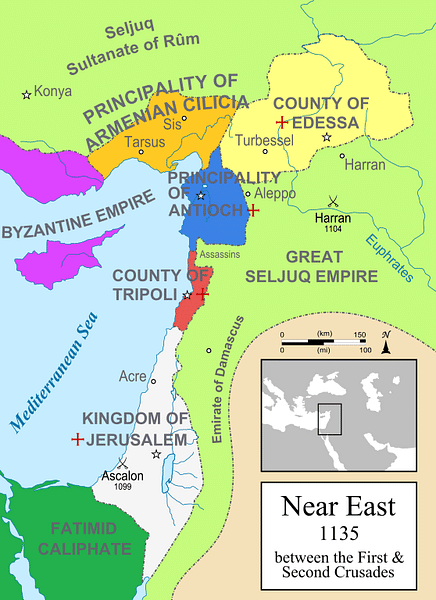

The Crusader States (aka the Latin East or Outremer) were created after the First Crusade (1095-1102 CE) in order to keep hold of the territorial gains made by Christian armies in the Middle East. The four small states were the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Edessa, the County of Tripoli, and the Principality of Antioch. The Westerners managed to maintain a political presence in the region until 1291 CE but were constantly hampered by dynastic rivalries, a lack of fighting men, underwhelming support from Western Europe, and the military prowess of such Muslim leaders as Zangi, Nur ad-Din (sometimes also given as Nur al-Din), and Saladin.

First Crusade & Creation

The First Crusade was launched by Pope Urban II (r. 1088-1099 CE) in response to the rise of the Muslim Seljuk Turks in the Middle East and their capture of Jerusalem in 1087 CE. The Seljuks were only taking over from Fatimids of Egypt, but they posed a serious threat to the Byzantine Empire, and its emperor, Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118 CE), asked for help from the West. After Urban II's rallying speech at the Council of Clermont in November 1095 CE, a Crusader army was assembled numbering around 60,000 men and including some 6,000 knights.

On arrival in the Holy Land, the Crusade was remarkably successful for such a complex international military operation in unfamiliar territory. Nicaea was captured in 1097 CE, Edessa in March 1098 CE, and Antioch shortly after in June. Jerusalem was captured in July 1099 CE, and a Muslim army defeated was at the Battle of Ascalon in August of the same year. In May 1101 CE Caesarea and Acre fell. In 1109 CE Tripolis was captured, followed by Beirut and Sidon in 1110 CE and Tyre in 1124 CE. These territorial acquisitions, helped enormously by the presence of fleets from the Italian city-states of Venice, Genoa and Pisa, would form the basis of the newly created Crusader States.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem

The most important of the Crusader States was the Kingdom of Jerusalem which controlled a narrow strip of coastal lands from Jaffa in the south to Beirut in the north. The kingdom controlled various fiefdoms, including Acre, Tyre, Nablus, Sidon and Caesarea. Godfrey of Bouillon, who had been one of the key leaders during the siege of Jerusalem in the First Crusade, was made the first king of Jerusalem and given command of a small garrison in the city (around 300 knights and 2,000 infantry). The Norman Arnulf of Choques was made patriarch or bishop of Jerusalem. The capital had a population of around 20,000, a figure which rose to 30,000 over the next century.

The County of Edessa

In March 1098 CE, Baldwin of Boulogne took control of Edessa (modern Urfa, southeast Turkey) and the County of Edessa was formed, the first of the Crusader States. Although Baldwin had, in effect, usurped power from the ruling Christian Armenians, he did promote a mixing of Western and Armenian nobility through marriages, making the County of Edessa the most integrated of the four Crusader-created states. The County, although covering the largest territory of any Crusader State, was a vassal state to the more important and powerful Latin polities of Antioch and Jerusalem, and functioned, in particular, as a military shield to Antioch further to the west, even if its small army necessitated truces and alliances with its Muslim neighbours to survive.

The County of Tripoli

The County of Tripoli, with its capital at the important seaport of Tripolis (modern Tripoli), then the most important port of Damascus, covered an area which is today Lebanon and was founded by Raymond of Toulouse. Raymond's army had captured Tripolis after a lengthy siege in 1109 CE with the help of Byzantine emperor Alexios I, for which Raymond had to swear an oath of loyalty. Thus, the County gave the Byzantines influence in the region, even under Alexios' successors. In contrast, it was the most independent Crusader State from the far-reaching political tentacles of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The County was divided into semi-independent lordships with each controlling an important port or castle. As a consequence of this arrangement, the County was perhaps the weakest, politically speaking of the Crusader States.

The Principality of Antioch

The Principality of Antioch, with its capital at Antioch, the great ancient city of culture and trade, was founded by the Norman Bohemund and extended by his successor Tancred of Lecce (r. 1105-1112 CE). The principality was another Crusader State that the Byzantine Empire - the former owners of that territory, of course - took a perpetual interest in, even though Bohemund refused to return Antioch as he had promised before the Crusade. On occasion, the Principality was formally subject to Byzantine rule, as, for example, in 1137 CE when Raymond of Poitiers (r. 1136-1149 CE) ceded control to John II Komnenos (r. 1118-1143 CE) after the emperor had laid siege to the capital. In 1161 CE the daughter of Raymond, Maria of Antioch, married Emperor Manuel I (r. 1143-1180 CE), sealing the close alliance between the Principality and the Byzantine Empire. A particular feature of the Principality compared to the other Crusader States was that the Christians (albeit mostly Eastern ones) made up a majority of the population because of the region's historical ties to Byzantium.

Defending the Levant

After a large part of the First Crusade army went home, the Crusaders States were left perpetually short of manpower, despite several later crusades trying to help, all without very much success. The European nobles who divided up the territory between themselves were, at least in theory, supposed to provide fighting men for the combined Latin army when required, with the king of the Kingdom of Jerusalem as the overall leader. However, there was often bitter rivalries and a distinct lack of cooperation between the Western nobles, even occasional civil wars. The King of Jerusalem had to use skilled diplomacy and the gifts of titles and lands to keep the barons of the Crusader States on his side. When everyone did pull together, there was a core army of around 1,500 knights (around 650 each from Jerusalem and Antioch plus 100 each from Edessa and Tripoli). These were supplemented with conscripted infantry and mercenaries.

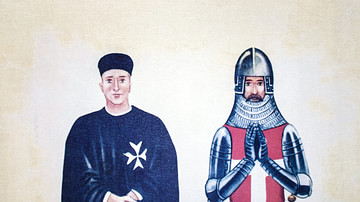

One aspect of the new situation in the region that was in the westerners' favour, though, was the creation of the two main military orders: the Knight Templars and the Knights Hospitaller. These independent bodies of professional knights who lived much like monks, were the best-equipped and best-trained soldiers on either side, Christian or Muslim. The knights of the two military orders, several hundred from each, were often given strategic passes and castles to man, these fortifications being helpful refuges but also a means to control the surrounding territory and provide bases from which to launch sorties against the enemy. One of the most impressive such castles was Krak des Chevaliers in Syria.

Government & Populations

The four states functioned much as other medieval monarchies in contemporary Europe. The ruler, either the king, prince or count as the case may be, was an absolute monarch but they did, because of their dependency on nobles providing warriors to the collective defence, hold councils of consultation. At Jerusalem, for example, the large estate owners, along with leading church figures and representatives of the military orders, attended a regular public debating forum, a parlement, in which opinions were aired and decisions made on such issues as taxes and foreign diplomacy. The Crusader States were politically weak throughout most of their existence because of squabbles over supremacy between themselves, continuous debates over successions, assassinations, intermarriages for political gain, the loss of key figures in warfare, and a general lack of long-term strategic planning to ensure their own continued survival.

Initially, there were massacres of local populations in the Crusader States as the European nobles imposed their feudal system of governance on the region, but the westerners soon realised that to hold on to their gains they needed the support of the extraordinarily diverse local populations. Indeed, Christians were outnumbered 5:1 by Muslims. Consequently, there grew a toleration of non-Christian religions, albeit with some restrictions and with those groups having to endure discriminatory laws and taxes (which were actually lower than in Muslim-controlled areas). The populations of the Crusaders states were certainly cosmopolitan, the larger groups consisting of Greek Orthodox Christians, Armenian Christians, Jews, Bedouin Arabs, and Muslims of various sects. Nevertheless, almost all positions of authority - both secular and in the Church - were monopolised by the Franks, as the locals called the Crusader settlers.

As most Crusaders came from France, the official language of the Crusader States was langue d'oeil, which was then spoken in northern France and by the Normans. In contrast, most of the indigenous population, whatever their religion, spoke either Arabic or Greek (or both). The linguistic and religious barriers, as well as those between ruler and ruled, meant that there was very little cultural integration between the westerners and the people they lorded over. Rather, contact was limited to legal, economic, and administrative affairs. If there was any cultural integration, it was most felt on the Franks' side and best seen in their adoption of local customs. It is also true that settlers from the west were not always nobles and every profession imaginable set themselves up for a new and difficult life in the Middle East. Perhaps these more ordinary folks did integrate a little more with the locals, at least in the more cosmopolitan cities. Life in the rural communities, though, continued much as before the Crusaders had arrived.

Economy

Another aspect of life which carried on much as before was trade, which thrived regardless of politics or race as goods travelled from the east and west and vice versa. The Levant often functioned as the middleman charging import and export duties on goods that passed through (between 4 and 25% of their total value). Acre, in particular, became a great Mediterranean trading port, and the Italian maritime states were ever-present, gaining lucrative local advantages in return for vital military aid. Important home-grown products included sugar cane, olive oil, and cereals. Another lucrative source of revenue was the movement of pilgrims keen to see for themselves the sights of the Holy Land. Such travellers had to pay a tax at their port of entry, and they contributed to the economy by spending their money on board and lodgings as well as souvenirs. Consequently, the Kingdom of Jerusalem, although always having to pay hefty bills of defence (paying soldiers and building fortifications) was rich enough to mint its own gold coinage which at that time only Sicily could manage in Europe.

The larger cities were thriving commercial centres with many foreign traders either temporarily or permanently settled in them. Merchants came from Arabia, Iraq, Byzantium, North Africa, and Italy. Markets were a focal point of commercial activity, Jerusalem famously had several covered streets for vendors, including the 'Street of Bad Cooking', probably a street where all manner of takeaway food could be bought. There were other specialised markets like that of silk in Tripolis and so locals could purchase in these markets a wide variety of goods such as basic foodstuffs, leather goods, cloth, furs, metal goods, and exotic imports like spices. Cities had specialised industrial quarters where tanneries, abattoirs, blacksmiths, and many others produced the goods needed for the community. Stonemasons were much in demand as, without a plentiful supply of wood in many areas, new buildings, churches, monasteries, and even new villages were largely built of stone.

The Muslim Fightback

Although the Crusader States initially benefitted from the political and religious disunity amongst the independent Muslim leaders in the region, it was only a matter of time before they grouped together under a single charismatic leader and made serious attempts to regain the losses of the First Crusade. In the second quarter of the 12th century CE, the Muslim expansion in the region went up a gear thanks to the arrival of one such leader, Imad ad-Din Zangi (r. 1127-1146 CE), the Muslim independent ruler of Mosul and Aleppo. Edessa fell on Christmas Eve 1144 CE to Zangi after a four-week siege, and this was the original motivation for the launch of the Second Crusade (1147-1149 CE). Before the international campaign could get underway, though, Edessa was brutally sacked by Zangi's successor Nur ad-Din in 1146 CE.

The Second Crusade was a complete failure. Defeat at Dorylaion in Asia Minor on 25 October 1147 CE and the failed siege of Damascus in July 1148 CE led to its swift abandonment, and the Crusader States were back on their own again. Nur ad-Din continued to consolidate his empire, and he took Antioch on 29 June 1149 CE and then captured Raymond, the Count of Edessa, thus bringing an end to what was left of the County of Edessa in 1150 CE. Even worse than this, another charismatic Muslim leader would soon appear and once again change the political and religious map of the Middle East: Saladin.

Saladin was the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193 CE), and his vision was to unite the Muslim world and destroy the Christian presence in the Middle East. Saladin's first big blow was the destruction of a Latin army led by the Kingdom of Jerusalem at the Battle of Hattin in July 1187 CE. Shortly after and with no Franks warriors left to defend it, Jerusalem itself was taken in September. Saladin had been as good as his word but the West would not give up their presence so easily. The Latin East had all but collapsed, only Tyre remained in Christian hands under the command of Conrad of Montferrat, as well as a handful of castles, but they would prove crucial for the next stage of the seemingly never-ending war.

Pope Gregory VIII (r. 1187 CE) launched the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE) which boasted three monarchs as its joint leaders. Faring a little better than the previous crusade it still turned out to be a great disappointment, Acre was captured in 1191 CE but, without sufficient resources to capture and keep it, Jerusalem was left in Muslim hands. Acre thus became the new capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Latin East as a whole.

The Crusaders would, against all odds, rule Jerusalem again from 1229 to 1243 CE, thanks to the Sixth Crusade (1228-1229 CE) and the negotiating skills of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (r. 1220-1250 CE). Frederick managed to strike a deal with al-Kamil, then the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1218-1238 CE), and Jerusalem was handed over to Christian control with the proviso that Muslim pilgrims could freely enter the city. Al-Kamil was having his own problems in controlling his large empire, especially rebel Damascus, and Jerusalem had no military or economic value at that time.

The pendulum of fate swung again when the allies of the Ayyubid Dynasty (the successors of Saladin), the nomadic Khorezmians (Khwarismians), captured Jerusalem on 23 August 1244 CE. The Ayyubid control of the Middle East was greatly strengthened when a large Latin army and its Muslim allies from Damascus and Homs was defeated at the battle of La Forbie (Harbiya) in Gaza on 17 October 1244 CE. Over 1,000 knights were killed in the battle, a disaster from which the Crusader States never really recovered.

The Mamluk Conquest

As the 13th century CE wore on, so the threat to the Crusader States increased. The Seventh Crusade (1248-1254 CE) attacked Egypt and was a flop, a situation not improved by the dismal Eighth Crusade (1270 CE). Between the two, the Crusades leader, Louis IX of France (r. 1226-1270 CE), did stay on in the Middle East and he helped to refortify some of the cities of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, notably Sidon, Jaffa, and Caesarea. However, in 1268 CE Antioch was sacked by the Mamluks who were based in Egypt and led by the gifted former general Baibars (r. 1260-1277 CE). The region saw a brand new threat, too, the ever-expanding Mongol Empire. The Mongols, moving relentlessly westwards, made raids on Ascalon and Jerusalem. When a Mongol garrison was established at Gaza, an attack on Sidon quickly followed in August 1260 CE.

Aid came from an unexpected quarter when Baibars pushed the Mongols back to the Euphrates River but he then took over much of the Latin East so that only two pockets remained around Acre and Antioch. Finally, mighty Acre fell in 1291 CE and the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Latin East now only existed as a refuge on Cyprus; what was left of the Crusaders States was absorbed into the Mamluk Sultanate which would rule in the region until 1517 CE.