The Crusades were a series of military campaigns organised by popes and Christian western powers to take Jerusalem and the Holy Land back from Muslim control and then defend those gains. There were eight major official crusades between 1095 and 1270, as well as many more unofficial ones.

Although there were many crusades, none would be as successful as the first, and by 1291 the Crusader-created states in the Middle East were absorbed into the Mamluk Sultanate. The idea of crusading was applied more successfully (for Christians) to other regions, notably in the Baltic against European pagans and in the Iberian Peninsula against the Muslim Moors.

Involving emperors, kings, and Europe's nobility, as well as thousands of knights and more humble warriors, the Crusades would have tremendous consequences for all involved. The effects, besides the obvious death, ruined lives, destruction and wasted resources, ranged from the collapse of the Byzantine Empire to a souring of relations and intolerance between religions and peoples in the East and West which still blights governments and societies today.

The Causes of the Crusades

The 11th century First Crusade (1095-1102) set a precedent for the heady mix of politics, religion, and violence that would drive all the future campaigns. The Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081-1118) saw an opportunity to gain western military aid in defeating the Muslim Seljuks who were eating away at his empire in Asia Minor. When the Seljuks took over Jerusalem (from their fellow Muslims, not the Christians who had lost the city centuries earlier) in 1087, this provided the catalyst to mobilise western Christians into action. Pope Urban II (r. 1088-1099) responded to this call for help, motivated by a desire to strengthen the Papacy and milk the prestige to become the undisputed head of the whole Christian church including the Orthodox East. Taking back the Holy City of Jerusalem and such sites as the Holy Sepulchre, considered the tomb of Jesus Christ, after four centuries of Muslim control would be a real coup. Consequently, the Pope issued a Papal Legate and set in motion a preaching campaign across Europe, which appealed for western nobles and knights to sharpen their swords, suit up and get themselves over to the Holy Land to defend Christendom's most precious sites and any Christians there in danger.

The warriors who 'took the cross', as the oath to crusade was known, and made the incredibly arduous journey to fight in a foreign land were motivated by any number of things. First and foremost was the religious aspect - the defence of Christians and the faith, they were promised by the Pope, brought a remission of sins and a fast-track route to Heaven. There were also ideals of chivalry and doing the right thing (although chivalry was in its infancy at the time of the First Crusade), peer and family pressure, the chance to gain material wealth, perhaps even land and titles, and the desire to travel and see the great holy sites in person. Many warriors had far less glamorous ambitions and were simply compelled to follow their lords, some sought to escape debts and justice, others merely sought a decent living with regular meals included. These motivations would continue to guarantee large numbers of recruits throughout all subsequent campaigns.

The First Crusade

Against all odds, the international military expedition of the First Crusade overcame the difficulties of logistics and the skills of the enemy to recapture first Antioch in June 1098 and then the big one, Jerusalem on 15 July 1099. With their heavy cavalry, shining armour, siege technology, and military know-how, the western knights sprung a surprise on the Muslims that would not be repeated. The slaughter of Muslims after the fall of Jerusalem would not be forgotten either. There had been a few cock-ups along the way, like the annihilation of the People's Crusade, a band of non-professional rabble, and a fair amount of deaths due to plagues, disease, and famine, but overall the success of the First Crusade astonished even the organisers themselves. Multinational cooperative warfare could reap dividends, it seemed, and this was the moment when the merchants started to show an interest in the crusades too.

The Crusader States

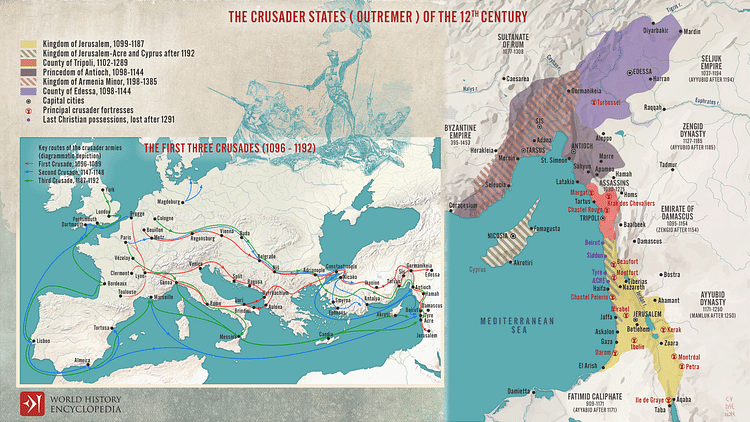

To defend the territory now in Christian hands, four Crusader States were formed: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, County of Edessa, County of Tripoli, and Principality of Antioch. Collectively, these were known as the Latin East or Outremer. The trade between the West and East, which went through these states, and the lucrative contracts to ship crusaders to the Levant attracted the merchants of such cities as Venice, Pisa, Genoa, and Marseille. Military orders sprang up in the Crusader States, such as the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller, which were able bodies of professional knights who lived as monks and who were given the job of defending key castles and passing pilgrims. Unfortunately for Christendom, the Crusader States always suffered a shortage of manpower and bickering between the nobles who had settled in them. Theirs was not to be an easy existence over the next century.

The Second Crusade

In 1144 CE the city of Edessa in Upper Mesopotamia was captured by the Muslim Seljuk leader Imad ad-Din Zangi (r. 1127-1146), the independent ruler of Mosul (in Iraq) and Aleppo (in Syria), and many Christians were killed or enslaved. This would spark off another crusade in the 12th century to get it back again. The German king Conrad III (r. 1138-1152) and Louis VII, the king of France (r. 1137-1180), led the Second Crusade of 1147-9, but this royal seal of approval did not bring success. Zangi's death only brought an even more determined figure on the scene, his successor Nur ad-Din (sometimes also given as Nur al-Din, r. 1146-1174), who sought to bind the Muslim world together in a holy war against the Christians in the Levant. Two big defeats at the hands of the Seljuks in 1147 and 1148 knocked the stuffing out of the Crusader armies, and their last-ditch attempt to salvage something honourable from the campaign, a siege of Damascus in June 1148, was another miserable failure. The next year Nur ad-Din captured Antioch, and the County of Edessa ceased to exist by 1150.

The Reconquista

In 1147, the Second Crusaders had stopped off at Lisbon en route to the East to assist King Alfonso Henriques of Portugal (r. 1139-1185) capture that city from the Muslims. This was part of the ongoing rise of the northern Christian statelets in Iberia who were eager to push the Muslim Moors out of southern Spain, the so-called Reconquista (the Reconquest, although the Muslims had been there since the early 8th century). The popes were more than happy to support this campaign and widen the idea of crusading to include the Moors as yet another enemy of the West. The same spiritual benefits were offered to those who fought in the Middle East or Iberia. The Spanish and Portuguese nobility were also keen to have the backing of a higher authority and the manpower and financial resources it promised. New local military orders sprang up, and the campaigns were remarkably successful so that only Granada remained in Muslim hands after the mid-13th century.

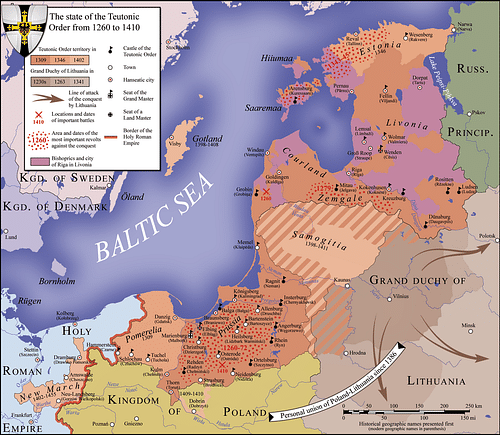

The Northern Crusades

A third arena for the crusades, again backed by the popes and wider Church infrastructure, was the Baltic and those areas bordering German territories which continued to be pagan. The Northern Crusades of the 12th to 15th century were first conducted by a Saxon army led by German and Danish nobles who selected the pagan Wends (aka Western Slavs) as their target in 1147. This was a whole new facet of crusading: the active conversion of non-Christians as opposed to liberating territory held by infidels. The crusades would continue thereafter, largely conducted by the military order of Teutonic Knights who called upon knights from across Europe to help them. The order in effect carved out its own state in Prussia and then moved on to what is today Lithuania and Estonia. Quite often brutally converting pagans and probably more motivated by land and wealth acquisition than anything else, the Crusades were so successful in their aims that the Teutonic Knights did themselves out of a job and, by the end of the 14th century, had to focus instead, and with much more meagre results, on the Poles, Ottoman Turks, and Russians.

The Third Crusade

Back in the Middle East, the fate of the three remaining Crusader States was becoming even more precarious. The new star Muslim leader, Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193) won a great victory against a Latin East army at the Battle of Hattin in 1187 CE and then immediately took Jerusalem. These events would bring on the Third Crusade (1189-1192). Perhaps the most glamorous of all the campaigns, this time there were two western kings and an emperor in command, hence its other name of 'the Kings' Crusade'. The three big names were: Frederick I Barbarossa, King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1152-1190) Philip II of France (r. 1180-1223) and Richard I 'the Lionhearted' of England (r. 1189-1199).

Despite the royal pedigree, things got off to the worst possible start for the Crusaders when Frederick drowned in a river on his way to the Holy Land in June 1190. Richard's presence did finally end the siege of Acre in the Christians' favour in July 1191, after the English king had already caused a stir by capturing Cyprus en route. Marching towards Jaffa, the Christian army scored another victory at the Battle of Arsuf in September 1191, but by the time the force got to Jerusalem, it was felt they could not take the city, and even if they did, the still largely intact army of Saladin would almost certainly and immediately take it back again. The end result of the Third Crusade was a mere consolation prize: a treaty which allowed Christian pilgrims to travel to the Holy Land unmolested and a strip of land around Acre. Still, it was a vital foothold and one which inspired many future crusades to expand it into something rather better.

Later Crusades

The subsequent crusades were very much a story of the Christians shooting their crossbows into their own feet. The Fourth Crusade (1202-1204) somehow managed to identify Constantinople, the greatest Christian city in the world, as the prime target. Papal ambitions, the financial greed of the Venetians, and a century of mutual suspicion between the East and the Western parts of the former Roman Empire all created a storm of aggression that resulted in the sacking of the Byzantine Empire's capital in 1204. The Empire was carved up between Venice and its allies, its riches and relics spirited away back to Europe.

The Fifth Crusade (1217-1221) saw a change of strategy as the western powers identified the best way to recapture the Holy Land from the Muslims - now dominated by the Ayyubid dynasty (1174-1250) - was to attack the enemy's soft underbelly in Egypt first. Despite the success, after an arduous siege, of taking Damietta on the Nile in November 1219, the westerners' lack of regard for local conditions and proper logistical support spelt their doom at the Battle of Mansourah in August 1221.

The Sixth Crusade (1228-1229) saw negotiation achieve what warfare had not. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (r. 1220-1250), who had been much criticised for not participating in the Fifth Crusade, managed to strike a deal with al-Kamil, then the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1218-1238), and Jerusalem was handed over to Christian control with the proviso that Muslim pilgrims could freely enter the city. Al-Kamil was having his own problems in controlling his large empire, especially rebel Damascus, and Jerusalem had no military or economic value at that time, only a religious significance, making it a cheap bargaining chip to avoid a distracting war with Frederick's army.

The Seventh Crusade (1248-1254) was launched after a Christian army was defeated at the battle of La Forbie in October 1244. Led by the French king Louis IX (r. 1226-1270), the Crusaders repeated the strategy of the Fifth Crusade and achieved only the same miserable results: the acquisition of Damietta and then total defeat at Mansourah. Louis was even captured, although he was later ransomed. The French king would have another go in the Eighth Crusade of 1270.

In 1250 the Mamluk Sultanate had taken over from the Ayyubid Dynasty, and they had a formidable leader in the gifted former general Baibars (r. 1260-1277). Louis IX once more attacked North Africa, but the king died of dysentery attacking Tunis in 1270, and with him so too did the Crusade. The Mamluks, meanwhile, extended their domination of the Near East and captured Acre in 1291, so definitively eliminating the Crusader States.

The Consequences of the Crusades

The Crusades had tremendous consequences for all those involved. Besides the obvious death, destruction and hardships the wars caused, they also had significant political and social effects. The Byzantine Empire ceased to be, the popes became the de facto leaders of the Christian Church, the Italian maritime states cornered the Mediterranean market in East-West trade, the Balkans were Christianized, and the Iberian peninsula saw the Moors pushed back to North Africa. The idea of crusading was stretched even further to provide a religious justification for the conquest of the New World in the 15th and 16th century. The sheer cost of the crusades saw the royal houses of Europe grow in power as that of the barons and nobles correspondingly declined. People travelled a little more, especially on pilgrimages, and they read and sang songs about the crusades, opening up a little wider their view of the world, even if it turned out to be a prejudiced one for many.

In the longer term, there was the development of the military orders, which eventually became tied with chivalry, many of which exist in one form or another today. Europeans developed a greater sense of their mutual common identity and culture, which also resulted in a sharper degree of xenophobia against non-Christians - Jews and heretics, in particular. Literature and art perpetuated crusading legends on both sides - Christian and Muslim, creating heroes and tragedies in a complex web of myth, imagery, and language which would be applied, very often inaccurately, to the problems and conflicts of the 21st century.