The art of the Etruscans, who flourished in central Italy between the 8th and 3rd century BCE, is renowned for its vitality and often vivid colouring. Wall paintings were especially vibrant and frequently capture scenes of Etruscans enjoying themselves at parties and banquets. Terracotta additions to buildings were another Etruscan speciality, as were carved bronze mirrors and fine figure sculpture in bronze and terracotta. Minor arts are perhaps best represented by intricate gold jewellery pieces and the distinctive black pottery known as bucchero whose shapes like the kantharos cup would inspire Greek potters.

Influences & Developments

The identification of what exactly is Etruscan art - a difficult enough question for any culture - is made more complicated by the fact that Etruria was never a single unified state but was, rather, a collection of independent city-states who formed both alliances and rivalries with each other over time. These cities, although culturally very similar, nevertheless produced artworks according to their own particular tastes and whims. Another difficulty is presented by the consequences of the Etruscans not living in isolation from other Mediterranean cultures. Ideas and art objects from Greece, Phoenicia, and the East reached Etruria via the long-established trade networks of the ancient Mediterranean. Greek artists also settled in Etruria from the 7th century BCE onwards and many works of Etruscan art are signed by artists with Greek names. Geography played its part, too, with coastal cities like Cerveteri due to their greater access to sea trade, being much more cosmopolitan in population and artistic outlook than more inland cities like Chiusi.

Greek art, and especially work from Athens, was highly esteemed then, as it still is now, but it is an error to imagine that Etruscan art was merely a poor copy of it. Etruscan and Greek artists in Etruria may have sometimes lacked the finer techniques of vase-painting and sculpture in stone that their contemporaries in Greece, Ionia, and Magna Graecia possessed but, at the same time, other art forms such as gem-cutting, goldwork, and terracotta sculpture show that the Etruscans had a greater technical knowledge in these areas. Whilst it is true that the Etruscans often tolerated works of a lower quality than would have been accepted in the Greek world, that does not mean they were not capable of producing art which was the equal of that produced elsewhere.

The Etruscans, then, greatly appreciated foreign art (their tombs are full of imported pieces) and they readily adopted ideas and forms prevalent in the art of other cultures, but they also added their own twists to conventions. The Etruscans, for example, produced nude statues of female deities before the Greeks did, and they uniquely blended Eastern motifs and subjects (especially mythological ones and creatures never present in Etruria like lions) with those from the Greek world and their own homegrown ideas which can be traced back to the indigenous Villanovan culture (c. 1000 - c. 750 BCE), the precursor to the Etruscan culture proper. This perpetual synthesis of ideas is perhaps best seen in funerary sculpture. Terracotta coffin lids with a reclining couple in the round may, when one inspects each figure closely, resemble Archaic Greek models but the physical attitude of the couple when seen as a pair and the affection between them which the artist has captured are entirely Etruscan.

Etruscan Tomb Painting

Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Etruscans is their beautifully painted tombs found in many sites like Tarquinia, Cerveteri, Chiusi, and Vulci. The paintings depict lively and colourful scenes from Etruscan mythology and daily life (especially banquets, hunting, and sports), heraldic figures, architectural features, and sometimes even the tomb's occupant themselves. Portions of the wall were often divided for specific types of decoration: a dado at the bottom, a large central space for scenes, a top cornice or entablature, and the triangular space, also reserved for painted scenes, reaching the ceiling like the pediment of a classical temple.

The colours used by Etruscan artists were made from paints of organic materials. There is very little use of shading until influence from Greek artists via Magna Graecia and their new chiaroscuro method with its strong contrasts of light and dark in the 4th century BCE. At Tarquinia, the paintings are applied to a thin base layer of plaster wash with the artists first drawing outlines using chalk or charcoal. In contrast, many of the wall paintings at Cerveteri and Veii were applied directly to the stone walls without a plaster underlayer. Only 2% of tombs were painted, and so they are a supreme example of conspicuous consumption by the Etruscan elite.

The late 4th-century BCE Francois Tomb at Vulci is an outstanding example of the art form and has a duel from Theban myth, a scene from the Iliad, and a battle scene between the city and local rivals, including some warriors with Roman names. Another fine example is the misleadingly named Tomb of the Lionesses at Tarquinia, built 530-520 BCE, which actually has two painted panthers, a large drinking party scene, and is interesting for its unusual checkered pattern ceiling. In the Tomb of the Monkey, also at Tarquinia, constructed 480-470 BCE, the ceiling has an interesting single painted coffer which has four sirens supporting a rosette with a four-leafed plant. The motif would reappear in later Roman and early Christian architecture but with angels instead of sirens.

Etruscan Sculpture

Etruria was fortunate to have rich metal resources, especially copper, iron, lead, and silver. The early Etruscans put these to good use, and bronze was used to manufacture a wide range of goods but our concern here is sculpture. Bronze was hammered, cut, cast using moulds or the lost-wax technique, embossed, engraved, and riveted in a full range of techniques. Many Etruscan towns set up workshops specialising in the production of bronze works, and to give an idea of the scale of production, the Romans were said to have looted more than 2,000 bronze statues when they attacked Volsinii (modern Orvieto) in 264 BCE, melting them down for coinage.

Bronze figurines, often with a small stone base, were a common form of votive offering at sanctuaries and other sacred sites. Some, as with those found at the Fonte Veneziana of Arretium, were originally covered in gold leaf. Most figurines are women in long chiton robes, naked males like the Greek kouroi, armed warriors, and naked youths. Sometimes gods were presented, especially Hercules. A common pose of votive figurines is to have one arm raised (perhaps in appeal) and holding an object - commonly a pomegranate, flowers, or a circular item of food (probably a cake or cheese). Fine examples of smaller bronze works include a 6th-century BCE figurine of a man making a votive offering from the 'Tomb of the Bronze Statuette of the Offering Bearer' at Populonia. Volterra was noted for its production of distinctive bronze figurines which are extremely tall and slim human figures with tiny heads. They are perhaps a relic of much earlier figures cut from sheet bronze or carved from wood and are curiously reminiscent of modern art sculpture.

Celebrated larger works include the Chimera of Arezzo. This fire-breathing monster from Greek mythology dates to the 5th or 4th century BCE and was probably part of a composition of pieces along with the hero Bellerophon, who killed the monster, and his winged horse Pegasus. There is an inscription on one leg which reads tinscvil or 'gift to Tin', indicating that it was a votive offering to the god Tin (aka Tinia), head of the Etruscan pantheon. It is currently on display in the Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Other famous works include the Mars of Todi, a striking near life-size youth wearing a cuirass and who once held a lance. In the other hand he was probably pouring a libation. It is now in the Vatican Museums in Rome. The Minerva of Arezzo is actually a representation of Menerva, the Etruscan goddess, who was the equivalent of the Greek goddess Athena and Roman deity Minerva. Finally, the Portrait of a Bearded Man often known as 'Brutus' after the first consul of Rome (without any connecting evidence) is a striking figure. Most art historians agree that on stylistic grounds it is an Etruscan work of around 300 BCE. It is now on display in the Capitoline Museums of Rome.

A Gallery of Etruscan Art

Etruscan Bronze Mirrors

The Etruscans were much criticised by their conquerors the Romans for being rather too effeminate and party-loving, and the high number of bronze mirrors found in their tombs and elsewhere only fuelled this reputation as the ancient Mediterranean's great narcissists. The mirrors, known to the Etruscans as malena or malstria, were first produced in quantity from the end of the 6th century BCE right through to the 2nd century BCE. Besides being an object of practical daily use, mirrors, with their finely carved backs, were a status symbol for aristocratic Etruscan women and were commonly given as part of a bride's dowry.

Designed to be held in the hand using a single handle, the reflective side of mirrors was made by highly polishing or silvering the surface. Some mirrors from the 4th century BCE onwards were protected by a concave cover attached by a single hinge. The inside of the lid was often polished to reflect extra light onto the face of the user while the outside carried cut-out reliefs filled with a lead backing. The flat reverse side of bronze mirrors, if not left plain (half the surviving examples are so), was an ideal canvas for engraved decoration, inscription, or even carved shallow relief. Some handles were painted or had carved relief scenes too.

The scenes and the people in them are often helpfully identified by accompanying inscriptions around the mirror edge. Popular subjects were wedding preparations, couples embracing, or a lady in the process of dressing. The most common subject for mirror decoration was mythology and scenes are often framed by a border of twisted ivy, vine, myrtle, or laurel leaves.

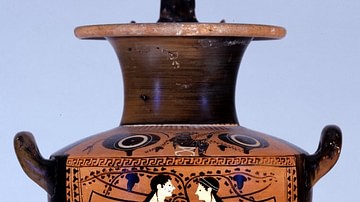

Etruscan Pottery

The first indigenous pottery of Etruria was the impasto pottery of the Villanovan culture. These relatively primitive wares contained many impurities in the clay and were fired only at a low temperature. By the end of the 8th century BCE, potters had managed to improve the quality. Small model houses and biconical urns (made of two vases with one smaller one acting as a lid for the other) were popular forms and used to store cremated human remains.

The next pottery type was red on white wares. This type of pottery, originating from Phoenicia, was produced in Etruria from the end of the 8th century BCE and into the 7th century BCE, particularly at Cerveteri and Veii. The red-coloured vessels were often covered with a white slip and then decorated with red geometric or floral designs. Alternatively, white was used to create designs on the unpainted red background. Large storage vases with small handled lids are common of this type and then kraters which also have scenes such as sea battles and marching warriors.

Largely replacing impasto wares from the 7th century BCE, bucchero was used for everyday purposes and as funerary and votive objects. Turned on the wheel, this new type of pottery had a more even firing and a distinctive glossy dark grey to black finish. Vessels were of all types and most often plain but they could be decorated with simple lines, spirals, and dotted fans incised onto the surface. Three-dimensional figures of humans and animals could also be added. The Etruscans were Mediterranean-wide traders, too, and bucchero was thus exported beyond Italy to places as far afield as Iberia, the Levant, and the Black Sea area. By the early 5th century BCE, bucchero was replaced by finer Etruscan pottery such as black- and red-figure wares influenced by imported Greek pottery of the period.

One unusual field of pottery which became a particular Etruscan speciality was the creation of terracotta roof decorations. The idea went back to the Villanovan culture but the Etruscans went one step further and produced life-size figure sculpture to decorate the roofs of their temples. The most impressive survivor from this field is the striding figure of Apollo from the c. 510 BCE Portonaccio Temple at Veii. Private buildings also had terracotta decoration in the form of plants, palms, and figurines, and terracotta plaques with scenes from mythology were often attached to outer walls of all types of buildings.

The Etruscans buried the cremated remains of the dead in funerary urns or decorated sarcophagi made of terracotta. Both types could feature a sculpted figure of the deceased on the lid and, in the case of sarcophagi, sometimes a couple. The most famous example of this latter type is the Sarcophagus of the Married Couple from Cerveteri, now in the Villa Giulia in Rome. In the Hellenistic Period the funerary arts really took off, and figures, although rendered in similar poses to the 6th-century BCE sarcophagi versions, become less idealised and more realistic portrayals of the dead. They usually portray only one individual and were originally painted in bright colours. The Sarcophagus of Seianti Thanunia Tlesnasa from Chiusi is an excellent example.

Legacy

The Etruscans were great collectors of foreign art but their own works were widely exported too. Bucchero wares, as we have seen, have been found across the Mediterranean from Spain to Syria. The Etruscans also traded with central and northern European tribes, and their artworks, thus, reached Celtic sites across the Alps in modern Switzerland and Germany. The greatest influence of Etruscan art, though, was on their immediate neighbours and cultural successors in general, the Romans. Rome conquered the Etruscan cities in the 3rd century BCE, but they remained independent centres of art production. Art works did reflect Roman tastes and culture, though, so that Etruscan and Roman art often became indistinguishable. An excellent example of the proximity between the two is the bronze statue of an orator from Pila, near modern Perugia. Cast in 90 BCE, the figure, with his toga and raised right arm, is as quintessentially Roman as a statue from the imperial period.

Aside from their obvious role in acting as a cultural link between the Greek world and ancient Rome, perhaps the most lasting legacy of Etruscan artists is the realism they sometimes tried to achieve in portraiture. Although still partially idealised, the funerary portraits on Etruscan sarcophagi are honest enough to reveal the physical flaws of the individual, and there is a clear attempt by artists to illustrate the unique personality of the individual. This was a concept that their Roman successors would also strive for and capture in very often moving portraits of private Roman citizens brilliantly rendered in paint, metal, and stone.