Guinevere is the Queen of Britain, wife of King Arthur, and lover of Sir Lancelot in the Arthurian Legends best known in their standardized form from Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur (1469 CE). She first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain (1136 CE) as Arthur's wife, who is abducted by his nephew Mordred and must be rescued by Arthur, but her character remained undeveloped until Chretien de Troyes (wrote c. 1159-1190 CE) made her central to the plot of his Lancelot or the Knight of the Cart (c. 1177 CE).

Chretien introduced the love affair between Lancelot and Guinevere, and writers following Chretien developed the Arthur-Guinevere-Lancelot plot through to its most complete treatment in Malory's work. Guinevere has been depicted as a duplicitous, treacherous, seducer and as an honest, loving wife trapped in circumstances beyond her control but all attempts to finally define her are lacking. She is frequently abducted and rescued in Arthurian tales and is, therefore, an early medieval paradigm of the damsel-in-distress literary figure. Modern-day scholars claim that she may have been a historical figure who was mythologized after her death as a “Celtic Persephone” or that she represents the sovereignty of Britain while still others claim she symbolizes the goddess Sophia (wisdom) as envisioned by the Cathars. No scholarly consensus has been reached on any of these claims which simply highlights the elusive nature of Guinevere in that she is as difficult to define for a reading audience as she is to the lords and knights of the tales.

Origin in Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1100-1155 CE) establishes the basic outline of the Arthurian Legend in his History of the Kings of Britain which features many of the central characters who would later be developed by other writers, including Guinevere. Geoffrey calls her Gwenhuvara from the Welsh name Gwenhwyvar. The name Gwenhwyvar (meaning unknown) appears in earlier Welsh folklore referencing a woman of bad reputation. According to Arthurian scholar Norris J. Lacy:

The Welsh preserved the tradition of her infidelity, blaming her to such an extent that in some parts of the country, as recently as the end of the last century, it was regarded as an insult to a girl's moral character to call her Guenevere. (262)

Precisely what this early Gwenhwyvar did is unclear, but in Geoffrey's work, she is simply Arthur's queen, a ward of the Lord Cador of Cornwall, and a great beauty of Roman descent. When Arthur leaves Britain to wage war on the continent, he leaves Guinevere in the care of his nephew Mordred who seduces her and usurps the throne. Arthur returns to rescue his queen and kingdom, but Guinevere, stricken with guilt, flees the kingdom and enters a nunnery. Mordred is killed in battle, and Arthur, mortally wounded, is taken away to the Isle of Avalon.

Geoffrey provides no details of Guinevere's infidelity, only writing:

Message was brought to [Arthur] that his nephew Mordred, unto whom he had committed the charge of Britain, had tyrannously and traitorously set the crown of the kingdom upon his own head and had linked himself in unhallowed union with Gwenhuvara the Queen in despite of her former marriage. (Book X.13)

Later writers such as Wace (c. 1110-1174 CE) and Layamon (c. late 12th/early 13th century CE) depict Guinevere as complicit in Mordred's coup, but theirs is the minority view, and most writers suggest she had no choice as she was abducted by Mordred along with the monarchy. The Welsh writer Caradoc of Lancarvan (12th century CE), a colleague of Geoffrey's, gives the first known story of Guinevere's abduction in his Life of Gildas (written c. 1136-1150 CE). Here she is taken by Lord Melvas, King of the Summer Land, and hidden away for over a year while Arthur searches for her. Once he finds her, he prepares to destroy Melvas' kingdom, but Gildas appears before hostilities begin and resolves the conflict peacefully: Guinevere is returned to Arthur and Melvas keeps his kingdom intact. As with Geoffrey, Caradoc gives no details on Guinevere's part in all of this. She remains a static figure with no personality or impact on the plot other than being Arthur's queen whom he must rescue.

Chretien de Troyes & Marie de France

Guinevere first comes into focus as an individual in the works of Chretien de Troyes and Marie de France (wrote c. 1160-1215 CE), two Provencal poets associated with Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204 CE) and her daughter Marie de Champagne (l. 1145-1198 CE). Eleanor and her daughter were patronesses of a number of poets writing in the genre of courtly love, a highly refined poetic medium of medieval literature featuring the truly novel concept of strong women with clearly defined characters. Eleanor and Marie were most likely models for a number of these women, and Chretien (who was patronized by Marie) says outright in his introduction to his Lancelot that the story was given to him by Marie who told him to form it as poetry.

As none of Marie de France's works can be authoritatively dated, it is not possible to tell whether her poem Lanval predates Chretien's Lancelot. It is probable that Marie's work is later because she frequently inverts a central paradigm of courtly love (in which a woman needs a man to rescue her) and has women rescue themselves, a man, or both. In her poem, the main character is Lanval, a knight of Arthur's court, who rides off after feeling insulted and enters the world of the fairy princess. The two fall in love and he spends some time there before he feels he should return to court. The princess makes him swear to keep their love a secret and, if he does, she will come to him when he most needs her; Lanval promises and then departs.

Back at court, Lanval is propositioned by Guinevere who is depicted as a sultry seductress, unfaithful to the king with his knights. Lanval refuses her and she accuses him of cowardice and then of homosexuality because no 'real man' could refuse her. Lanval feels he must safeguard his honor and explains he cannot have sex with Guinevere because he is in love with the fairy princess, thereby breaking his vow. Guinevere, in a plot twist taken from Joseph's story in the biblical Book of Genesis, runs to Arthur and accuses Lanval of trying to seduce her. Arthur has Lanval arrested and put on trial. It seems he will be convicted and, although he calls for his fairy princess, he is expecting no help from her since he broke his vow. At the last minute, however, she appears and rescues him, pulling him up behind her on her horse and riding off toward her realm.

This story is most likely later than Chretien's work for two reasons:

- His Lancelot was popular reading and Marie's inversion of the rescue of a knight by a lady would have resonated with an audience,

- Marie's Guinevere picks up on the confidence-arrogance which is integral to Chretien's Guinevere.

In Chretien's Lancelot, Guinevere is abducted by the Lord Meleagant and locked in a high tower. Arthur's knights pursue but Lancelot outpaces all of them, riding his horse so hard that it dies and he must continue on foot. He meets a dwarf driving a cart who says he will take the knight to the queen if he will consent to ride in the cart. Since carts were associated with criminals and lower-class people, Lancelot hesitates but quickly agrees. He is then humiliated throughout his journey to Meleagant's land for riding in a cart but finally reaches Guinevere and attempts her rescue. She refuses him, however, because he hesitated before stepping into the cart, meaning he valued his reputation and honor more than his devotion to her. Lancelot must then win her back by first losing to unworthy opponents at a tournament and then winning when Guinevere tells him to. In the end, he kills Meleagant and frees the queen, who rewards him with a polite embrace in public even though, privately, they have been lovers.

Marie and Chretien both present a recognizable individual with specific motivation for her actions. In Marie's story, Guinevere does not love her husband and is bored, so she has affairs with Arthur's knights. In Chretien's tale, Guinevere does seem to care for Arthur but, as with the Tristan and Isolde paradigm, her true love is Arthur's best friend and greatest knight, Lancelot.

Guinevere as Goddess

Modern-day scholars contend that Guinevere's character and circumstances symbolize a deeper meaning than simple entertainment for the courts of medieval Europe. Roger Sherman Loomis argues that Guinevere is a “Celtic Persephone” who, like the Greek goddess, “dies” and is then “reborn” through her abduction and rescue (which appear in a number of other tales following Chretien's). Her infidelity is reminiscent of ancient fertility goddesses who cannot be held to the same standards as mortals. One is therefore not to judge Guinevere so much as admire her for being true to her divine self in a culture which expected women to constantly conform to the desires of men.

Scholar Caitlin Matthews claims that Guinevere is Britain's version of Eriu (Eire), the goddess of the sovereignty of Ireland and that this is supported by the Welsh tradition that Arthur was married to three different Guineveres who correspond to the tripartite Celtic goddess. The three Guineveres are mirror images of the Celtic goddesses Eriu, Banba, and Fodla of Ireland. The abductions would represent different temporal rulers trying to hold sovereignty which cannot be claimed by a single monarch but belongs to the people.

The scholar Denis de Rougemont, among others, has suggested that courtly love poetry in general, and that of Marie de France and Chretien de Troyes in particular, are allegorical representations of the heretical sect of the Cathars who flourished in Southern France at the same time the poets were writing. The Cathars opposed the teachings of the Catholic Church claiming they were corrupt, that most of the Bible was written by Satan, and the Catholic clergy was little more than corrupt hypocrites who cared more for wealth and pleasure than serving others. Central to Cathar belief was a goddess Sophia (wisdom) and de Rougemont's claim argues that the lady character in courtly love poetry is Sophia and the knight is the devout Cathar who serves her and must protect or rescue her from her abductor, the Church. Guinevere, according to this theory, is held by Arthur, defender of the Church, and is rescued by Lancelot, the French knight who is bound only by his devotion to his lady.

The Vulgate Cycle & Malory

If it is true that the poetry of 12th century CE Southern France was actually a heretical religious allegory, its message was abruptly silenced by the Church's Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229 CE) which destroyed the Cathars as well as the culture of the region. The Arthurian legends continued to develop in the 13th century CE but authors increasingly Christianized the tales so that the Grail (introduced by Chretien as simply a magical vessel) became the cup of Christ at the Last Supper and the purpose of Arthur's knights on their quests was no longer chivalric romance but an effort to find the Holy Grail.

These tales continued to captivate audiences, however, and were rendered in prose in the work known as the Vulgate Cycle (1215-1235 CE, also known as the Lancelot-Grail Cycle). This work is significant in that it is the first time Arthurian material is presented in prose. Prior to this, romances were written as poetry while prose was reserved for serious works on history, philosophy, or theology. It is a telling detail on the importance of the Arthurian Legend that it was considered worthy of prose treatment. This work was then edited sometime between 1240-1250 CE for clarity and form; the edited version is known as the Post-Vulgate Cycle.

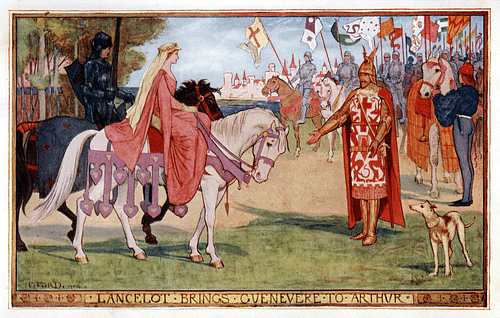

The Post-Vulgate Cycle was Thomas Malory's primary source in writing Le Morte D'Arthur in 1469 CE. In Malory's version, Guinevere is the daughter of King Leodegrance of Camelerd who had served Arthur's father, Uther Pendragon, and still had the Round Table Uther had given him. She is betrothed to Arthur after he helps Leodegrance defeat a rival king but, for Arthur, the marriage is more than just a reward or seal on an alliance. In Chapter 18:1, Arthur first sees Guinevere and falls instantly in love with her. In 18:3, he tells Merlin he will have only Guinevere as his wife. Merlin warns him that she will not be faithful but will fall in love with a knight called Lancelot, and he with her, and they will betray him. Arthur tells Merlin how none of that matters and asks him to arrange the marriage. Leodegrance sends his daughter to Arthur's court along with the Round Table and 100 knights, and the wedding ceremony is as grand as any ever seen but Guinevere is silent throughout the entire proceeding.

However she may have felt toward her marriage, Guinevere is all courtesy and grace. Norris J. Lacy comments:

She is the epic Queen of history and chronicle, bounteous of her gifts to the knights of the Round Table, and she is also the tragic heroine of romance, deserving of our pity for having been given in marriage to a man she must respect but cannot love and fated to love a man she cannot marry. (263)

As soon as Lancelot enters the story, Guinevere falls in love with him as deeply as Arthur had for her. As long as their affair remains secret, all is well, but as they become more open in their affection for each other, suspicions are raised and Arthur is forced to act against his wife and best friend. Lancelot escapes before he can be arrested but Guinevere is taken and condemned to execution at the stake. Arthur knows Lancelot will come to rescue the queen, which he does, and she then returns to him and asks forgiveness. Arthur is encouraged to blame Lancelot more than Guinevere and, against his wishes, he mobilizes his army to go after his former friend. He leaves Guinevere and his kingdom in Mordred's care (in Malory, he is Arthur's illegitimate son) but, as in Geoffrey of Monmouth, Mordred betrays Arthur and attempts to abduct Guinevere and seize power.

Arthur hurries home and meets Mordred in battle at Camlann. Lancelot has pledged his help but never arrives. Arthur kills Mordred but is badly wounded and is helped from the field by Sir Bedevere; almost all of Arthur's other knights are killed. After returning the sword Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake, Bedevere helps Arthur into a barge which takes him away to the Isle of Avalon. Guinevere enters a convent where she spends the rest of her life in service to others. She only sees Lancelot once after her return to Arthur to say goodbye and tell him of her intention to renounce the world; he follows the same path as she, and Malory suggests that they are united spiritually in a way they would never again be physically.

Conclusion

Guinevere plays a significant role in many other Arthurian works than those mentioned here and has continued to fascinate readers for centuries. The English poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892 CE) revived the Arthurian Legend with his Idylls of the King in 1859 CE and portrays Guinevere as a fallen woman who recognizes her failings and his forgiven by her lord. Tennyson's Guinevere reflects the values of the Victorian Age he was writing in, and every writer since then has followed this same paradigm. Even a cursory knowledge of how Guinevere has been portrayed in film over just the past 50 years shows how she is constantly re-imagined to fit the values of the time while the other characters in the legends remain more or less the same.

Guinevere is a genteel queen torn between the husband she loves and her feelings for his best friend in the musical Camelot (film version 1967 CE), while in Excalibur (1981 CE) she is a flirtatious free spirit who embraces her affair with Lancelot as simple fun. In First Knight (1995 CE) she is the independent woman, rebelling against her marriage to the older Arthur, drawn to Lancelot, the dashing knight her own age, and in King Arthur (2004 CE) she is a Pict warrior-princess, owing nothing to any man and choosing her own path. As interesting as all these portrayals may be, none of them capture the essence of Guinevere any more than the medieval tales which gave birth to her. Probably more than any other literary character, Guinevere continues to intrigue and resist any attempts at defining her.