The Hill of Tara is an ancient Neolithic Age site in County Meath, Ireland. It was known as the seat of the High Kings of Ireland, the site of coronations, a place of assembly for the enacting and reading of laws, and for religious festivals.

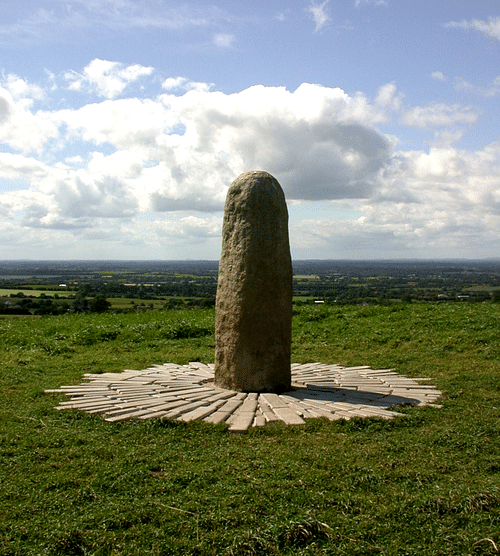

The oldest monument at the site is the Mound of the Hostages, a Neolithic passage tomb, dating from c. 3000 BCE. The ring forts and evidence of other enclosures, such as the Banquet Hall, date from a later period. The Lia Fail (stone of destiny), by which the ancient kings were inaugurated, still stands on the hill. The site is also associated with the Tuatha De Danaan, the pre-Celtic peoples of Ireland and with the mystical elements they came to embody.

The great sabbats of pagan Ireland were announced by a bonfire on the hill which, at an elevation of 646 feet (197 m), would have been seen for many miles in every direction. It is said that St. Patrick announced the arrival of Christianity in Ireland by lighting his own large bonfire across from Tara at the Hill of Slane before going there to preach before King Laoghaire in 432/433 CE. The name comes from the Gaelic Cnoc na Teamhrach, which is often translated as "place of great prospect", though it has also been argued it comes from a corruption of Tea-Mur or Teamhair, burial place of the ancient queen Tea.

Tara in Legend

The Hill of Tara plays a key role in the 11th/12th century CE work The Book of Invasions, considered today a mythical construct of Ireland's early history by Christian scribes, who attempted to link Ireland's past with biblical narratives and Greek and Roman history. It tells the story of early colonization by descendants of the biblical Noah and then a series of invasions culminating in the coming of the Milesians from Spain. Although the work is regarded as folklore and myth today, it was understood as history by its original audience and for centuries afterward.

The Milesians defeated the people known as the Tuatha De Danaan (the children of the goddess Dana) and, according to one version of the legend in the Book of Leinster, the Milesian poet and judge, Amergin, was given the task of deciding which race would hold what land.

He divided Ireland between the two by giving his own people all the land above ground and the Tuatha De Danaan everything underground. This legend explains the homes of the 'fairy folk' of Ireland who live in caves, under the ground in holes, and in the nooks and crevices of rocks.

Two Milesian brothers, leaders of their people, divided the land between them with Eremon taking the northern half and Eber the south. With the land divided, the brothers then divided their armies equally and then the craftsmen and the cooks and so on with men and women of all the arts until there remained only two left: a harpist and a poet. The writer Seumas MacManus relates the rest of the tale: "Drawing lots for these, the harper fell to Eremon and the poet to Eber - which explains why, ever since, the North of Ireland has been celebrated for music, and the South for song" (11). The brothers, with everything equally divided, then settled down to a long peace.

It was the Hill of Tara which broke the peace. Eber's wife told him she wished to have the three most lovely hills in Ireland and, especially, the most beautiful and scenic: Tara. Tara belonged to Eremon in the north and, when Eremon's wife (Tea) heard of the request,she became furious that this woman could not be content in her own realm. The two of them argued and drew their husbands into the fight resulting in war. Tea died and was buried at Tara, giving the hill her name (Teamhair = Hill of Tara). Eber was defeated and Eremon, now sole ruler of Ireland, was crowned at Tara. This event marked the beginning of the tradition of the High Kings of Ireland's coronations at the site.

Tara & Cormac MacArt

Another version of Tara's past claims that the Fir Bolgs, the race that lived in Ireland before the invasion of the Tuatha De Danaan, were the first to build at Tara and inaugurate kings there. The rituals of the Fir Bolgs were replaced by the Tuatha De Danaan and then by the Milesians, but the importance of the site never diminished. A great banquet hall was built for feasts, houses for dignitaries to stay in during assemblies, other homes for the ladies, a meeting house, and ring forts.

Special attention was given to the placement of these buildings in aligning them with astronomical and solar directions. The Neolithic Mound of the Hostages is aligned so that at two of the important sabbats, Imbolc (in February) and Samhain (in late October), the morning sun illuminates the mound's otherwise dark passage. The Mound of the Hostages is so named because it was the place where hostages were exchanged between kings and dignitaries.

This suggests how important the site was in antiquity since the exchange of hostages would have been chosen on ground where both parties felt safe. The king was considered a wise father-figure to the people who, in theory at least, would work for the common good above his own interests.

The High Kings of Ireland were chosen by a system of rotation among chiefs; they did not assume the throne through any divine right or heredity, and their inaugurations at Tara were great festivals. According to legend the stone of destiny would cry out when the rightful king was chosen. Two standing stones, which the would-be king would ride toward at a gallop, were said to part if he were worthy to rule.

The king considered most worthy was Cormac MacArt (c. 3rd century CE) under whose rule Tara flourished. Although many myths and legends surround this king's reign, he is considered by scholars to have actually existed. He is said to be the son or grandson of the great hero Conn of the Hundred Battles and is always described in terms of great respect as the law-giver and protector of the people.

The famous Brehon Laws, considered among the most equitable law codes ever written, are attributed to Cormac MacArt. Women's rights were protected and, unlike in other cultures of the 3rd century CE, women could practice any profession they desired and were considered partners of their husbands in marriage instead of property.

Whether the Fir Bolg actually had a banquet hall in their day is unknown, but it is recorded that Cormac MacArt built a grand hall with 14 entrances, 760 feet long by 45 feet high. He is also supposed to have built a palace at Tara and a number of other structures and monuments. The outline of what may have been a long building can still be seen at Tara in the present day, although whether this actually is a remnant of a banquet house is disputed, as are the claims regarding the other buildings Cormac MacArt is said to have raised.

There is still a great deal to excavate at Tara, however, and it is possible that the ancient writers will be vindicated yet. MacManus cites the 14th century CE Book of Ballymote, a work which would be considered semi-mythical today, which describes Cormac MacArt as "A noble, illustrious king" in whose time "there were neither woundings nor robberies...but every one enjoyed his own, in peace" (47). The writer T.W. Rolleston expands on Cormac MacArt's reign and especially his building projects, writing:

Also he rebuilt the ramparts of Tara and made it strong, and he enlarged the great banqueting hall and made pillars of cedar in it ornamented with plates of bronze, and painted its lime-white walls in patterns of red and blue. Palaces for the women he also made there, and store-houses, and halls for the fighting men—never was Tara so populous or so glorious before or since. (178)

Cormac MacArt was considered a great pagan king who, toward the end of his life, converted to Christianity. Whether all the events of his life which came to be written down actually happened, the story of his conversion is in keeping with the Christianization of pagan heroes and rituals which became commonplace in Ireland after the coming of St. Patrick.

St. Patrick & Tara

St. Patrick is thought to arrived in Ireland as a missionary in 432/433 CE. Patrick was a Roman citizen who had been captured and sold into slavery in Ireland years before. He escaped, crediting God for his deliverance, and returned to Britain. There he studied to become a priest, was ordained, and returned to Ireland as a missionary.

In c. 433 CE, according to legend, the High King Laoghaire forbade the lighting of any fires on a given night approaching the pagan festival of Ostara when the great bonfire would be lit on the Hill of Tara. This sabbat corresponded to the Christian observance of Easter, and so Patrick lit his own fire on the Hill of Slane, across from Tara, which burned so brightly that the king saw it and sent his soldiers to arrest whoever had defied him and to douse the flame.

Patrick and his followers eluded the soldiers through a miracle by which they appeared as a herd of deer and made their way to the king's seat at Tara. Once there, Patrick defeated the king's druids in debate and then preached to the king and his comrades. As this was going on, the soldiers who had been sent to arrest him returned to report Patrick's fire could not be put out. The story ends with a number of the king's court converting to Christianity while the king himself rejected the new faith but was impressed enough by Patrick to allow him to continue his mission.

In the present day, once one enters the gate at the Hill of Tara, St. Patrick's statue is the first monument one sees and, behind it, a church. In keeping with the story of the Easter fire, the statue and the church are fitting symbols of the triumph of Christianity in Ireland. Unlike the struggle between the old faith and the new in other countries, the conversion of Ireland by St. Patrick and his followers was relatively peaceful, and the old statues of pagan gods gave way to those of Patrick and other Christian saints and symbols. In the churchyard there are two ancient standing stones, one of which represents the pagan fertility god Cernunnos. A visitor to the site today will note that St. Patrick's statue is quite prominent, while Cernunnos' could be mistaken for a large rock.

The Hill of Tara After St. Patrick

Whether one accepts the tales of Patrick and his fire or any of the others, his mission to Ireland was a great success. The Hill of Tara, however, diminished as a political and religious centre as Christianity grew in power and other sites rose in prominence as they came to be associated with Christian centres of learning or miracles performed by Patrick or later Saints. Tara's standing diminished further after the Norman Invasion of 1169 CE and then the later establishment of English rule in Ireland which, for centuries, tried to suppress Irish language and lore.

The memory of the ancient seat of the high kings continued to resonate with the people, however. Tara has been the site of peaceful protests and fierce conflicts such as the Rising of 1798 CE or the non-violent demonstration of 1843 CE staged there by Irish patriot and orator Daniel O'Connell. From prehistory to the present, Tara has always been the "pleasantest of hills" and has played a significant role in Irish history.

Since 2007 CE the site has been the focus of a controversy between developers of the M3 Motorway and the preservation group Save Tara over construction of a motorway near the site. Preservationists argue the development will destroy vital aspects of the site and obliterate millennia of history, while M3 Motorway representatives claim otherwise, pointing out how historical preservation and 21st century development have been balanced at other sites throughout Ireland and will be at Tara.

Both sides of the controversy offer relevant arguments for their claims, but it should be noted that the World Monuments Fund placed Tara on its list of 100 Most Endangered Sites in 2008 CE. and the proposed motorway development influenced that designation. Still, both sides have won significant numbers of supporters globally to their causes, highlighting the importance of the Hill of Tara to people not just of Ireland but around the world.

![A Short Description of the Hill of Tara. [With a Map.]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41hzLJTCiyL._SL160_.jpg)