King John of England (aka John Lackland) ruled from 1199 to 1216 CE and he has gone down in history as one of the very worst of English kings, both for his character and his failures. He lost the Angevin-Plantagenet lands in France and so crippled England financially that the barons rebelled and forced him to sign the Magna Carta charter of liberties in 1215 CE.

The son of Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189 CE) and Eleanor of Aquitaine (c. 1122-1204 CE), John succeeded his elder brother Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199 CE) as king. The celebrated Magna Carta that he was obliged to sign limited royal power and emphasised the primacy of the law over all, including the monarchy. Another name frequently associated with the king is Robin Hood, the legendary outlaw who stole from the rich and gave to the poor, but there is little historical evidence of such a figure and, if he did exist, that he ever troubled John. Following his death while fleeing a French invasion force, King John was succeeded by his young son Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272 CE)

Early Life

John was born on 24 December 1167 CE at Oxford, the youngest of four sons born to King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Given no particular inheritance of note, he was nicknamed 'LackLand' meaning he had no lands, although his father did pack him off to Ireland in 1185 CE with the title Lord of Ireland. John, acting as viceroy, managed to upset both the English and Irish during his brief stay, and he was back in England after only four months in the job.

Rebellion Against Henry II

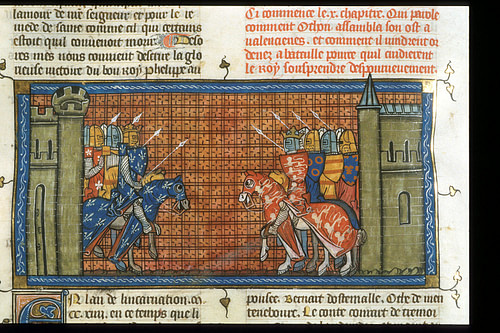

Richard and his younger brother John challenged their father Henry II in 1188-9 CE. The rebel sons formed an alliance with Philip II, the new King of France (r. 1180-1223 CE). The rebellion was supported by Eleanor of Aquitaine. Losing control of both Maine and Touraine, Henry eventually agreed to peace terms which recognised Richard as his sole heir. When the king died shortly after, Richard was crowned his successor in Westminster Abbey on 2 September 1189 CE. Also part of his kingdom were those lands in France still belonging to his family the Angevins (aka Plantagenets): Normandy, Maine, and Aquitaine. Richard refused to give John Aquitaine, as he had promised his father he would, and this only acerbated the rivalry between the two brothers.

Rebellion Against Richard & Succession

While Richard was fighting abroad during the Third Crusade (1189-1192 CE) and then held in captivity by the Holy Roman Emperor, John took the opportunity to try and usurp the throne. The help of Philip II of France did not prove decisive, though, and Richard's able ministers Hubert Walter organised enough resistance to thwart the rebellion. When Richard returned briefly to England in 1194 CE, he forgave his brother his excessive ambition and even nominated him as his official successor.

In 1194 CE Richard campaigned in France to defend his Angevin-Plantagenet lands, but disaster struck during his siege of the castle of Chalus on 6 April 1199 CE. Hit by an arrow and dying of gangrene, Richard left no heir and so John was made the new king of England; he was crowned on 27 May 1199 CE at Westminster Abbey.

Philip II of France

John had married Isabella of Gloucester on 29 August 1189 CE and, obviously partial to the name, married Isabella of Angouleme (a county in Aquitaine) after his first marriage was annulled on 24 August 1200 CE. This second attachment proved troublesome for the English king since the second Isabella had been previously promised to a French count, Hugh de Lusignan, and so Philip II of France took exception to the wedding. Philip confiscated all of the territory in France then held by the English crown (John, like his Norman predecessors, was also the Duke of Normandy). John responded by sending an army but then once again spoiled relationships in 1203 CE by killing his 17-year old nephew Prince Arthur, the son of the late Geoffrey, Count of Brittany (1158-1186 CE), whom he saw as a threat with his claim to the English throne (which Philip II supported). This treachery cost John the support of many French barons, and with it all the English king's lands north of the Loire River by 1206 CE.

The blow was one of prestige as well as territory, the king henceforward earning another derogatory nickname, 'John Softsword'. This was perhaps a little unfair as John did manage to do some things right. He resisted the incursions of William the Lion, king of Scotland (r. 1165-1214 CE) into the north of England and forced him to accept John as his feudal overlord in September 1209 CE. Then he quashed the Irish rebellion of 1210 CE, infamously capturing the wife and eldest son of the rebellious baron William de Briouze and seemingly then allowing them to starve to death in captivity in Windsor Castle. John gained another impressive victory against the troublesome Welsh prince Llywelyn of Gwynedd, aka Llywelyn the Great (r. 1194-1240), in 1211 CE. Clearly, the medieval chroniclers who painted a dark picture of an evil and useless king were not quite telling the whole story. It is perhaps not a coincidence that these chroniclers were men of the cloth, and the medieval Church was the next enemy to be made by the king.

Pope Innocent II

Back in England, King John may not have been talentless but he was certainly managing to make himself one of the most unpopular kings in English history. The next group he upset was officials of the Church after his refusal to endorse Stephen Langton for the post of Archbishop of Canterbury. As Langton was the papal candidate, Pope Innocent III (r. 1198-1216 CE) excommunicated John in November 1209 CE and ordered the closure of all churches. The idea that the king was chosen by God to rule, the so-called divine right of kings, was looking a little problematic for John to use as a basis for his authority now that the Church had abandoned him. In 1212 CE the Pope even went so far as to declare that John had no longer any legal right to call himself king. The king backed down, Langton was appointed archbishop and John accepted that England and Ireland were fiefs of the Papacy.

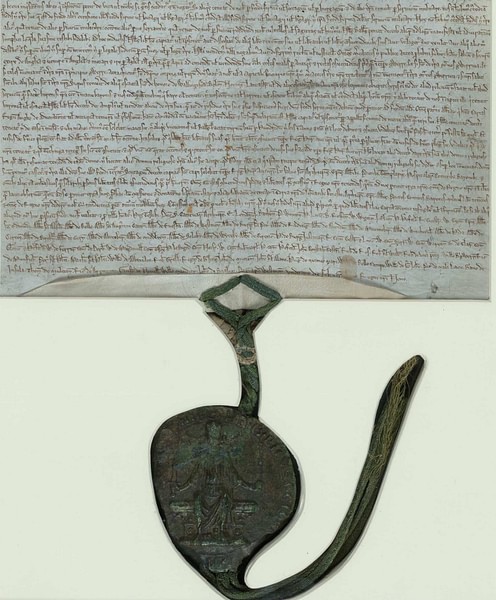

Magna Carta

Upsetting foreigners and the Church was par for the course for most medieval rulers but things really started to go badly for John when he began to upset the powerful barons. The king's heavy taxation to pay for his French campaigns was crippling, even worse, there was no military gain to show for it. Another policy that irked the barons was the king's creation of his own royal courts to rival local courts, thereby redirecting fines paid by the guilty away from the barons and into his own treasure chest. John was certainly inventive on measures to increase his revenue, he even upped the fee barons had to pay the king when their daughters married, and a young baron now had to pay a fee when he inherited his father's property. If a baron died without an heir, the custom was to pass on the land to another noble but King John often kept such land for himself as long as possible, as he did with church lands. Merchants did not escape the king's clutches either, and they had to bear a great increase in taxes, too.

Another defeat to the French in 1214 CE at Bouvines was the last straw. The failure brought about a major uprising of barons and overtaxed merchants who, supported by Alexander II, king of Scotland (r. 1214-1249 CE), marched to London, not to support the king in another invasion of Normandy as he had requested, but to oblige him to sign the Magna Carta at Runnymede on 15 June 1215 CE. This charter of liberties curbed the power of the monarch and protected the feudal rights of the barons. The king could no longer seize lands arbitrarily or impose unreasonable taxes without first consulting the barons. Henceforward, the king would also have to consult a defined body of laws and customs before making declarations and all freemen (but not serfs) would be protected from royal officers and have the right to a fair trial. Thus, the Magna Carta became a symbol of the rule of law as the ultimate sovereign. In return for these concessions, the king was allowed to keep his crown and Archbishop Langton absolved him of his excommunication. The barons may have been acting out of self-interest rather than the good of the commoner but their collective action was a milestone and the beginning of a long and bloody road towards a constitutional monarchy.

Robin Hood

One name that is frequently associated with King John is Robin Hood, the 13th-century legendary outlaw who stole from the rich and gave to the poor in the area of Sherwood Forest, Nottingham. Robin represented the common man, hence his weapon was the bow and not the sword of a medieval knight. Unfortunately for romantics, there probably was no such individual. The only historical reference within the complex web of legendary tales is that a man called Robert or Robin 'Hood' was a wanted criminal in Yorkshire in 1230 CE. It is true, though, that there were other similar cases of men living in forests outside the law, notably one Geoffrey du Parc in Feckenham Forest, Worcestershire around 1280 CE (who, incidentally, also had his own priest amongst his group just like Robin had Friar Tuck).

Whatever its basis in actual events, the legend was real enough from the 14th century CE onwards and, although receiving changes and embellishments over subsequent centuries, it has remained a very popular myth and a particular favourite of filmmakers. In the most common version of the tale, Robin lives with his band of merry men in the forest where they live by their own laws and so they do not pay excessive taxes and can hunt wild animals freely (which was prohibited by the Norman kings of England). Robin's wife is Maid Marian and his enemy is the Sheriff of Nottingham, who is himself a representative of the nasty King John. The involvement of John is almost certainly a later addition, shifting the timing of the story to highlight the king of England's rapacious tax laws and the imposition of his own royal law courts.

Another connection with John, and another twist to the tale, is that Robin was actually of noble birth but had his lands taken from his family by the king as he schemed to oust his brother Richard while he and Robin were away on the Third Crusade. This later 16th-century CE embellishment may have been a reaction from the aristocracy, who were already a bit miffed about the popularity of a tale where the commoners get the upper hand; essentially then, Robin was made one of them, hence his success. A very similar story is told for the knight Fulk Fitzwarin (c. 1160–1258) who rebelled against King John and dwelt in a forest in Shropshire. Clearly, if any good-hearted rebel in English medieval literature needed a villain to go up against, John was the most popular candidate.

Barons' War & Death

Back to the actual history of John's reign. The king had still not quite grasped the principles of statehood, as shown when he went back on his word and ignored what he had signed in the Magna Carta. Inevitably, the barons sought to rid themselves of their sovereign, they refused to give up their occupation of London, and they invited another candidate, Prince Louis, son of Philip (and future Louis VIII of France, r. 1223-1226 CE) to be their king. A civil war broke out, often called the First Barons' War, between supporters of the two royal persons, and although John famously besieged and captured mighty Rochester Castle in October-November 1215 CE, Louis grabbed southeast England, including the Tower of London, and proclaimed himself king in May 1216 CE. In the same year, Louis managed to grab back Rochester Castle for the rebel cause. The hapless John even managed to lose some of the Crown Jewels in a river as he fled with his baggage train from Lincoln in October. Catching a fever, the king died on 18 October 1216 CE at Newark Castle; he was just 48. The dead and unlamented king was buried in Worcester Cathedral, as requested in his will. King John is the subject and title of a play by William Shakespeare (1564-1616 CE).

John was succeeded by his son Henry III (b. 1207 CE) who was crowned king of England on 28 October 1216 CE in Gloucester Cathedral. Henry, despite being only nine years old and having to pick up the pieces of a broken kingdom, would defeat the remaining rebel barons at Lincoln in May 1217 CE and go on to reign for 56 years until 1272 CE.