Lysistrata was the third and final of the peace plays written by the great Greek comic playwright Aristophanes (c. 445 - c. 386 BCE). Shown in 411 BCE at the Lenaea festival in Athens, it was written during the final years of the war between Athens and Sparta. The play is essentially a dream about peace. Many Greeks believed the war was bringing nothing but ruin to Greece, making it susceptible to Persian attack. So, in Aristophanes' play, the wives and mothers of the warring cities, led by the Athenian Lysistrata, came together with an ingenious solution. In order to force peace, the women decided to go on strike. This was not a typical work stoppage. Instead, there was to be no romantic relations of any kind with their husbands. Further, by occupying the Acropolis, home of the Athenian treasury, the women controlled access to the money necessary to finance the war. Together with the withholding of sex, both sides would soon be begging for peace.

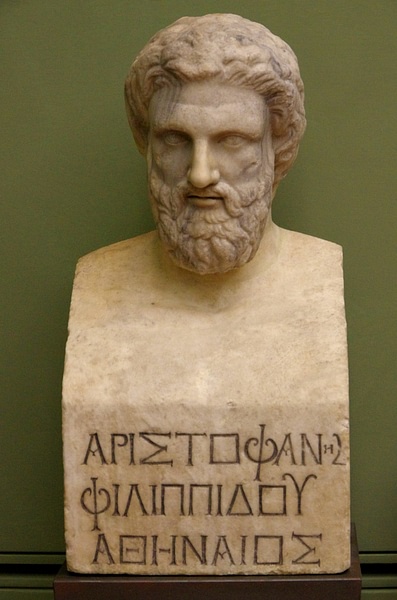

Aristophanes

As the author of at least forty plays, only eleven of which have survived, Aristophanes is considered by many to be the greatest poet of Greek comedy. Unfortunately, his works are the only examples to remain intact. By the time Aristophanes began to write, Greek theatre was in serious decline. However, much of the presentation of drama remained the same. There was the usual chorus of 24 as well as three actors who wore grotesque masks and costumes.

Little is known of his early life. Having most of his plays written between 427 and 386 BCE helps place his death around 386 BCE. A native of Athens, he was the son of Philippus and owned land on the island of Aegina. He had two sons, one of which became a playwright of minor comedies. Although participating little in Athenian politics, he was an outspoken critic, via his plays, of the Peloponnesian War. His portrayal and attack of the statesman Cleon in the play The Babylonians landed him in court in 426 BCE.

Although somewhat quiet on the subject of Athenian politics, Aristophanes opposed all changes in the traditional aspects of philosophy, education, poetry, and music. He was an outspoken critic of both the philosopher Socrates and his fellow playwright Euripides. Norman Cantor in his book Antiquity said the playwright reflected the conservative opinion of many Athenians, showing them to be people who valued old simplicity and morality. They viewed all new innovations as being subversive. His plays were a mixture of humor, indecency, gravity, and farce. Editor Moses Hadas in his book Greek Drama said while Aristophanes could write poetry that was delicate and refined, he could also, at the same time, demonstrate bawdiness and gaiety. Author Edith Hamilton, in her The Greek Way, said that all of life could be seen in the plays of Aristophanes; politics, war, pacifism, and religion.

Although Aristophanes is sometimes condemned for bringing drama down from the high level of Aeschylus, his plays, with their simplicity and vulgarity, were recognized and appreciated for their rich fantasy as well as humor and indecency. His comedy was a blend of wit and invention.

Background & characters

Athens was a city of unrest as Spartan armies loomed nearby. People were outraged at their ineffective leadership in both city government and on the battlefield. All of this served as ammunition for Aristophanes' play. In Lysistrata, the women of both Athens and Sparta go on strike to force the men to stop the war and make peace. Through the outspoken hero of the play, Lysistrata, Aristophanes is provided an avenue for his anti-war views. To him, war provided men with the opportunity for courage and a glorious death. Women, on the other hand, were immune. To them, war could only bring decades of misery as a bereaved wife or mother.

The play had a rather large cast of characters:

- Lysistrata

- Calonice

- Myrrhine

- Stratyllis

- the Spartan Lampito

- choruses of old men and women

- a magistrate

- three old women

- four young women

- Myrrhine's husband Cinesias

- a Spartan herald

- a Spartan peace delegate

- two Athenian peace delegates

- and a number of silent characters.

Plot

The play opens outside the Athenian homes of Lysistrata and her friend Calonice; one can see the Acropolis in the background. Lysistrata is obviously very anxious, looking right and left, waiting for the arrival of her friends:

…I'm really disappointed in womankind. All our husbands think we're such clever villains … I've called a meeting to discuss a very major matter, and they're all still fast asleep. (Sommerstein, 141)

Calonice tries to calm her, telling her that it is difficult for women to get out of the house, for they have much to do. She had spent several sleepless nights thinking about the problem before arriving at a solution. She is frantic. The whole future of the country - all of the Peloponnese and Athens - rests with them. Turning to Calonice, Lysistrata says:

… we women have the salvation of all Greece in our hands [...] I am going to bring it about that no man, for at least a generation, will raise a spear against another. (142)

As other women arrive, including the Spartan Lampito, Lysistrata chides them for being late. She poses a question if she found a way to end the war would they join her. Cautiously, they agree. She divulges her plan; the women are to renounce sex. If they do so, the men will become frustrated and surely make peace. Many, including Calonice, begin to walk away, thinking let the war continue. Believing it will bring peace, Lampito immediately agrees, and the others gradually side with her. To guarantee full cooperation they all must swear an oath.

As they take their oath, a loud shout of triumph rings out from the Acropolis; the citadel of Athena was now in their hands. Their plan was fairly simple. They were to occupy the Acropolis, and even if the men tried to take it by force, they would only submit on their terms. They plan is soon tested as a group of men arrives with crowbars and torches to break down the barred doors. They are joined by a small assembly of women, headed by the elderly Stratyllis, carrying pitchers of water. She turns to her comrades:

What have we here? A gang of male scum, that's what! No man who had any decency, or any respect for the gods, would behave like this! (154)

The male leader spins around, threatening her. She does not back down and along with the other women throw water on the men, extinguishing their torches. As they continue to argue - the leader calls her an old relic while she calls him an old corpse - a magistrate arrives with two slaves and several other officers. He exclaims:

Look at the way we pander to women's vices - we positively teach them to be wicked. That's why we get this sort of conspiracy. (156)

Lysistrata emerges from behind the door:

What's the use of crowbars? It's not crowbars we need, it's intelligence and common sense. (157)

One of the officers attempts to grab Lysistrata. As the magistrate and his officers attempt to charge the doors, Lysistrata calls for more women to come out. They charge the officers, punching and kicking. Beaten, the men pull back. The women withdraw inside the Acropolis. In desperation, the magistrate finally turns to Lysistrata and asks why they have barred themselves inside. Lysistrata tells him they want to stop the men from waging war. As they continue to argue Lysistrata finally says:

…we're in the prime of our lives, and how can we enjoy it, with our husbands always away on campaign and us left at home like widows? (164)

Unfortunately, she begins to realize that some of the women are losing loyalty to the cause. One husband, Cinesias, comes to the Acropolis, begging for his wife, Myrrhine, to come home. Despite his enticements, she refuses and returns to the other women. As he curses his wife, a Spartan herald approaches, claiming he is there to discuss a settlement. Cinesias tells him to return to Sparta and bring delegates with full power while he goes to the Council and asks for Athenian delegates.

The Spartan delegation arrives and is soon joined by Athenian delegates. They ask to speak to Lysistrata. She rebukes both sides:

Thus each of you is in the other's debt: Why don't you stop this war, this wickedness? Yes, why don't you make peace? What's in the way? (187)

She leads them into the Acropolis for food and drink and to discuss the terms of peace. In the end, she turns to the Spartans:

Well, gentlemen, so it's all happily settled, Spartans, here are your wives back …. now form up everyone, man beside wife and wife beside man, and let us have a dance of thanksgiving. (191)

Conclusion

Lysistrata is a play about peace. As with many of Aristophanes' plays, he used his characters to act as his voice. He detested the war and the effect it had on his beloved Athens. Since the war ended shortly after the play was produced, this became his third and final plea for peace. In the play, unlike reality, peace was miraculously negotiated, and the war came to a glorious end with both sides gathering together to eat and dance. The hero of the play, Lysistrata (whose name means "Liquidator of Armies") is a remarkable protagonist for many reasons. She demonstrates both a strong will and determination; she chastises her fellow women for their tardiness and later makes them take an oath to ensure their commitment. She faces the magistrate and calmly voices her demands; a plea for intelligence, not crowbars. As a woman, she realizes that she has little, if any, voice in the policy-making. However, she understands men, and through her resourcefulness, she is able to bring the two sides together to make peace.