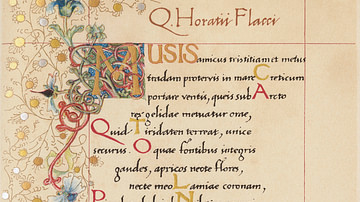

Medieval Folklore is a body of work, originally transmitted orally, which was composed between the 5th and 15th centuries in Europe. Although folktales are a common attribute of every civilization, and such stories were being told by cultures around the world during the medieval period, the phrase “medieval folklore” in the west almost always refers to European tales.

The word “folklore” was coined in 1846 by the British writer William John Thoms to replace the more awkward phrase “popular antiquities” which designated the stories, fables, proverbs, ballads, and legends of the common people. In time, folktales were written down and became static but originally they were dynamic and ever-changing stories passed from one generation to the next and moving between cultures as merchants carried the tales to other countries through trade.

Today there are standard versions of folktales, as well as numerous variations on those standards, which are studied by folklorists in an effort to better understand the culture that produced them. Folktales from the Near East and Asia were transmitted orally to Europe via trade through the Silk Road which accounts for some of these variations. Further changes to an original story are the result of storytellers embellishing upon a tale for a particular audience. The folktale continues to be a popular medium of entertainment in the present day and has been mined by film and television companies, as well as modern-day authors, for source material.

Types of Folklore

Tales composed (or at least popularly transmitted) in Europe between c. 476 (the fall of the Western Roman Empire) and 1453 (the fall of the Eastern Byzantine Empire) are considered Medieval Folklore. Scholar Christopher R. Fee defines the term in general:

Folklore refers to cultural “items” common to a particular community; such items may include stories, rituals, dances, songs, or any other aspect of life in that community that is imbued with some measure of shared experience, wisdom, or fundamental belief. Moreover, folklore entails the process of transmission of such shared community knowledge or tradition. (xviii)

Unlike literature, which is a written body of work transmitted by an author to a literate audience, folklore is conveyed orally and the storyteller is free to embellish on the tale for a particular audience. The performance of a tale, in fact, is considered integral to the very definition of a folktale. As these stories were told, and traveled between cultures, discernible motifs developed which were finally analyzed and cataloged by folklorists of the 19th century (such as Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm) who wrote them down.

As these tales became written literature, and different versions of a tale could be compared on a page, standard versions were established which correlated to various others. The story of a young girl who is victimized by her evil stepmother and stepsisters, for example, is not unique to the Cinderella story but shares that motif with many other stories.

The wide variation in these stories was of central interest to folklorists in the 19th century who were tracing the development of folklore in general and certain stories specifically. In 1910, the folklorist Antti Aarne developed a classification system to make the study of these tales easier. This system was then revised by another folklorist, Stith Thompson in 1928 and again in 1961. The Aarne-Thompson index (known as AT) of the Types of Folklore consisted of three categories:

- Animal Tales

- Ordinary Folktales

- Anecdotes and Jokes

In 2004, the Aarne-Thompson index was revised by folklorist Hans-Jorg Uther who expanded the branches of the index to delineate the categories further and expanded the definition of “medieval folklore” to include cultures beyond Europe. Today, the Aarne-Thompson-Uther index (ATU) categorizes folktales into seven distinct groups:

- Animal Tales

- Tales of Magic

- Religious Tales

- Realistic Tales

- Tales of the Stupid Ogre (or giant or devil)

- Anecdotes and Jokes

- Formula Tales

Each folktale is assigned a number (example: ATU 101) for reference and comparison with others. It should be remembered, however (as Fee points out) that “folklore” applies not only to tales but to any aspect of a culture that is transmitted orally and can equally apply to techniques and methods in leather-working or metallurgy or dress-making as to legends, ballads, and proverbs. Even so, the term is usually understood to refer to tales which fall in or close to one of the seven categories of the ATU Index.

Further, because folktales were so fluid in composition and performance, these categories should be understood as approximations. A so-called “formula tale” could have major religious or magical elements and might as easily be a “religious tale” or a “tale of magic” except that it follows a discernible formulaic pattern (a character insists that one thing must happen before something else can happen and so on). An animal tale, likewise, might have a religious message but since the principal characters are non-human, it is not categorized as a “religious tale”.

Animal Tales

Animal tales are best-known from the fables of Aesop. Aesop's fables were already a popular entertainment before they were collected and published by William Caxton in 1484 and many of the most popular motifs were reworked by medieval European storytellers. Among these is the story of the faithful dog who will not betray his master, epitomized in the story known as Old Sultan (ATU 101), collected by the Grimm Brothers in 1812.

The old dog Sultan hears his master tell his wife how, the next day, he plans on killing the dog because he is no longer useful. Sultan wanders into the woods where he meets his friend the wolf and explains his problem. The wolf proposes a plan in which he will come and snatch the couple's babe and Sultan will save it. The plan works perfectly and Sultan is saved; his master swears he can live there comfortably forever. A few days later, the wolf comes by and tells Sultan he will just be taking a stray sheep or so and the dog should not mind but Sultan refuses and protects his master's interests. The wolf is upset and challenges the dog to a fight to settle the debt but, in the end, realizes that what Sultan did was right.

The moral of the story is the value of personal integrity highlighted by the dog's faithfulness, the farmer's initial ingratitude, and the debt the dog owes to the wolf. Even though the farmer might not be worthy of the dog's loyalty, Old Sultan still remains faithful even to the point of refusing a favor to the friend who helped him.

Tales of Magic

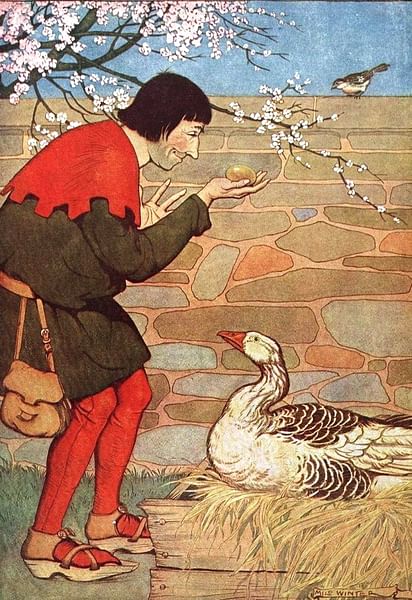

The fairy tale is categorized as a Tale of Magic and always has some supernatural element to the plot. In German, the language of the primary folklorists of the 19th century, they were known as Zaubermarchen (“wonder tales”). As noted, many folktales could fit into two or more of a folklorist's categories and many tales rely on supernatural characters or events to work. Fairy tales, however, require the supernatural – usually in the form of a charm, an enchanted animal or object, or a spirit – in order to work at all. In a Religious Tale, Jesus or another divine figure might appear but the story could work as well without the visitation; in a Tale of Magic, a supernatural encounter is vital to the plot.

An example of this is the tale of The White Snake (ATU 673) in which a handsome and faithful servant of the king eats a tiny bit of a small white snake and can then understand the language of the animals. This new gift comes in handy throughout the rest of the story in which he finds the queen's ring and is able to marry a beautiful princess all because he can understand animals. In helping various animals when he hears them complain of their situation, he makes friends who come to his aid throughout the story.

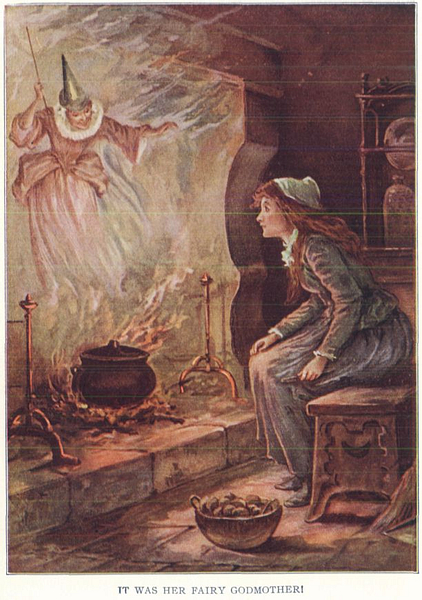

The fairy tale often focuses on a young hero – either of high or low birth – who must fight for (or rescue) a princess or noble maiden. Conversely, they feature the young woman as the main character who must be rescued (famously, Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty). The earliest versions of these tales are often much darker than the “standard” versions best known today.

In Cinderella, for example, the step-sisters cut off parts of their feet to fit them into the glass slipper and, in one version, are then condemned to dance themselves to death. In Sleeping Beauty, the heroine is raped by a king who then abandons her to return to his queen who, eventually, tries to murder Beauty's twin children to feed their corpses to her wayward husband. However the plot is manipulated, the featured couple winds up married and living together happily afterwards.

Religious Tales

The same cannot be said for Religious Tales which, in medieval folklore, always have a strong Christian moral and frequently turn out badly for the main character. Religious tales often begin with the line, “In those days when our Lord and St. Peter wandered upon the earth…” instead of the better-known “Once upon a time…” but, instead of placing the action in a biblical setting, the story always features contemporary elements of the Middle Ages. A popular setting is a blacksmith's shop which Jesus and Peter visit on their travels and perform some miracle out of the goodness of their hearts which the self-serving blacksmith will later try to replicate with disastrous results.

Another popular setting is the lone man or woman, of any occupation, who are tested by Jesus and Peter and fail spectacularly. An example of this is Gertrude's Bird (ATU 751A) in which a woman named Gertrude, recognized by a spot of red in her hair, is visited by Jesus and Peter who arrive at her house while she is baking and ask for food. As Gertrude rolls out the dough, she finds the loaf it makes is too large and decreases it bit by bit until she realizes anything she has is too much to give and tells the strangers to move along. Jesus becomes enraged and curses her for being so greedy. He changes her into a bird who must seek her food by pecking for it in dead trees and only getting water when it rains. The story explains the origin of the woodpecker as well as warning against the dangers of greed and refusing to offer hospitality to guests.

Realistic Tales

Realistic Tales also have a Christian moral and are often re-worked versions of famous parables from the Bible such as The Prodigal Son, The Unjust Servant, The Rich Fool, among others. Many of the so-called realistic tales emphasize how people get what they deserve either through divine or supernatural intervention, their own goodness and intelligence, or an evil-doer's carelessness and stupidity. One example of this is The Robber Bridegroom (ATU 955) in which a virtuous young woman is unwittingly betrothed to a cannibalistic criminal.

The miller of a small town agrees to give his beautiful daughter in marriage to a promising young stranger who seems to be of good breeding. After courting her a few months, the bridegroom invites the maiden to come alone to his cottage in the woods. When she arrives at the house, no one is home but an old woman in the basement who tells her she should never have come because her bridegroom regularly tricks young women to his cottage where he robs, kills, and then eats them. It is too late now for the maiden to escape but the old woman tells her to hide and she will later rescue her. Soon after, the robber bridegroom and his men come in with another young woman they rob and chop into pieces. One of the woman's fingers, with a ring on it, is accidentally tossed across the room where it lands behind a cask where the maiden is hiding. One of the robbers gets up to get the finger but the old woman coaxes him back to the table and then puts them all to sleep through a potion she slips into the stew.

The maiden and old women escape the cottage and return safely home. Later, when the marriage feast is given, the guests are all invited to tell stories and the maiden tells the story of her night in the bridegroom's cottage and produces the severed finger with the ring on it as proof. The bridegroom is arrested and he and his men are condemned and executed.

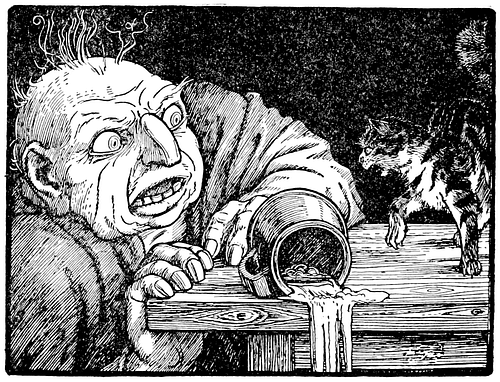

Tales of the Stupid Ogre

Tales of the Stupid Ogre include any stories concerning a powerful supernatural being like a witch, sorcerer, giant, or the devil who is in some way outsmarted by the hero or heroine. Among the best-known motifs is the clever good man who outwits the devil which serves as the basis for the 1824 short story The Devil and Tom Walker by Washington Irving which inspired the later, and better-known, story by Stephen Vincent Benet, The Devil and Daniel Webster in 1936.

Typical of this type is the story of Roland and the Maiden (ATU 1119) in which a good young maiden is forced to live with her wicked step-mother and step-sister who are witches. The step-mother plans to kill the maiden but the maiden tricks her into killing the step-sister and then flees with her friend and protector Roland. The couple are pursued by the witch who almost catches them twice but, each time, the maiden is able to disguise them until Roland, in the form of a magical musician, plays a tune the witch has to dance to until she dies. After further adventures, the couple eventually happily marry.

Anecdotes & Jokes

While the happy marriage is the natural end of many Stupid Ogre tales, the opposite is true of Anecdotes and Jokes which frequently make fun of unhappy couples and clumsy affairs. Typical of these tales is one with the telling title of Tom Totherhouse (ATU 1725) which deals with a deaf husband, his unfaithful wife, a servant-boy, and the neighbor Tom who cannot keep from visiting the other house on his road.

The wife of the house has been carrying on with Tom Totherhouse for some time when the servant boy bets her ten dollars that he will make her openly confess the affair. She accepts the bet and the boy then lays one trap after another to thwart and frustrate the lovers. He finally tricks Tom Totherhouse into believing the husband knows of the affair and is coming with an axe to kill him while, at the same time, telling the husband that Tom needs him to come over with his axe and fix Tom's plough. Tom sees him with the axe and runs away and the wife, seeing her husband bending down to pick up some pieces of bread the serving boy has left out in the yard, thinks he's gathering rocks to stone her and confesses.

Formula Tales

Formula Tales mostly follow a pattern in which a character gets into trouble and needs help but cannot receive it until a series of conditions, stipulated one after another by other characters, are met. In the story of The Death of Little Hen (ATU 2021) for example, a hen and a cock go out to the nut hill to eat after agreeing to share whatever they find. The hen finds a large nut and eats it without thinking of the cock and it becomes lodged in her throat. She calls out to the cock to run to the well to get water but, when he gets there, the well will give him no water unless he gets some thread from a nearby bride. The bride will not surrender the thread unless the cock first gets her a wreath from the willow, the willow will not comply until its condition is met and so on. By the time the cock returns to the hen she has choked to death and the same pattern, more or less, then repeats itself regarding her funeral procession.

Formula Tales most likely inspired the type of folk tune known as a cumulative song in which each verse builds on the previous one until an entire tale is told. The best-known examples of cumulative songs in the modern-day are Twelve Days of Christmas, Old McDonald Had a Farm, and Hole in the Bottom of the Sea, among others.

Conclusion

The underlying form of all folktales, no matter how they are categorized and defined, is shared experience. Folklore resonates through time because the themes are universal. The Stupid Ogre type of tale touches on people in power trying to exploit those weaker than they are and failing. The Formula Tale relies on the communal understanding of the importance of working together and keeping one's word. Realistic Tales and Religious Tales underscore the common understanding of morality and justice while also usually providing memorable examples of what can happen when one strays from the accepted norm and the other types serve similar purposes.

In a largely illiterate society, medieval folklore entertained while teaching the most important values of the community. Folklorists who have made these tales their life's work are able to understand what a society was like and what the people considered important based on the kinds of folk tales they told as well as which stories were borrowed – and then kept – from other cultures. Whichever category a tale might fall into, folk tales have the power to instantly engage and clearly communicate their message to an audience.