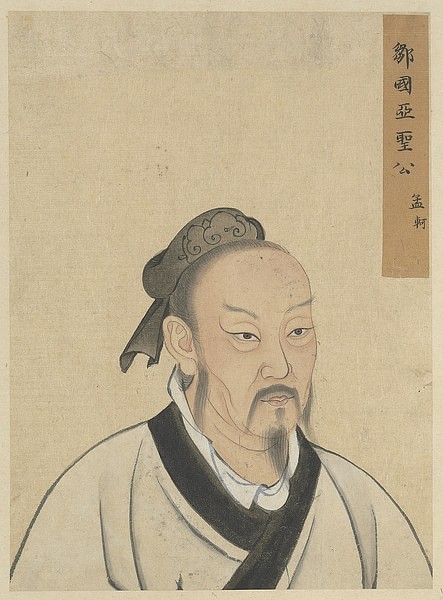

Mencius (l. 372-289 BCE, also known as Mang-Tze or Mang-Tzu) was a Confucian philosopher during The Warring States Period in China (c. 481-221 BCE) and is considered the greatest after Confucius himself for his interpretation, formulation, and dissemination of Confucian concepts. He is the fourth of the Five Great Sages of Confucianism beginning with Confucius himself:

- Confucius (l. 551-479 BCE)

- Zengzi (l. 505-435 BCE)

- Tzu-Ssu (also given as Zisi, l. c. 481-402 BCE)

- Mencius (l. 372-289 BCE)

- Xunzi (also given as Hun Kuang, l. c. 310 to c. 235 BCE)

All four, following Confucius, contributed significantly to Confucian philosophy but Mencius is regarded as the greatest for his skill in interpreting the concepts, his zeal in spreading them, and his formulation of the philosophy. At the same time, Xunzi, through his work, the Xunzi, is considered almost on par with Mencius as the philosopher who completed the Confucian vision by tempering its idealism with realism.

Mencius developed the Confucian concept of basic human goodness as his central claim, arguing that people will behave well if they are encouraged to develop virtuous thoughts and habits. He established his own school, and, after teaching, he traveled between the antagonistic states of the period counseling the rulers to abandon their wars and join together to help the people. According to historian Will Durant, Mencius tried to impress a central message on these kings:

The good ruler would war, not against other countries, but against the common enemy – poverty – for it is out of poverty and ignorance that crime and disorder come. (684)

As with the work of a number of other philosophers of this period (such as Mo Ti, l. 479-391 BCE), Mencius' efforts were in vain and, disappointed, he abandoned public life to live in relative seclusion with his students until his death. His formulation and codification of Confucian thought would define the philosophy which was eventually adopted as the national belief system under the Han Dynasty (202 BCE to 220 CE) and has informed Chinese culture ever since.

Early Life & Work

His name is actually Mang-Tze or Mang-Tzu but he is best known as Mencius, the Latinized version used by Christian missionaries writing about Chinese philosophy, who also changed K'ung-fu-Tze to 'Confucius'. Born to a poor family, his father died when he was young and his mother, Zhang, raised her son alone. Mencius' mother is legendary for her devotion to her son and remains a model of maternity in China today.

The popular Chinese saying translated as “Mencius' mother, three moves” refers to her moving three times in an effort to find the best place to raise her child. They originally lived near a graveyard, but she noticed that her son was beginning to emulate the behavior of the undertaker and professional mourners. She found this unacceptable and so moved into town where the boy began to mimic the activities of the nearby merchants and imitate the sounds from the local slaughterhouse. This, too, she found unworthy of her son and so moved again to a small home near a school. Here, her son began to imitate the behavior, speech, and discipline of the teachers and so he became a scholar.

A further story exemplifying his mother's virtues tells of a time when she found he was neglecting his studies and so cut in half the cloth she had been steadily weaving. Mencius was shocked at this behavior, but his mother told him it was no more than what he, himself, was doing in not finishing his schoolwork and so rendering it worthless. Mencius learned the lesson and returned to his studies.

He became an official and teacher at the Jixa Academy in the state of Qi and served with distinction until his mother died. At that time, he took a leave of absence and buried her with such expense and ceremony that his students, and many others, were scandalized. Mencius merely cited Confucius in this regard and explained that the devotion one owes one's mother should be expressed fittingly at all times and, certainly, through her funeral and mourning rites.

Mencius' School and Political Thought

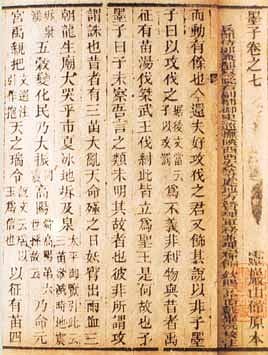

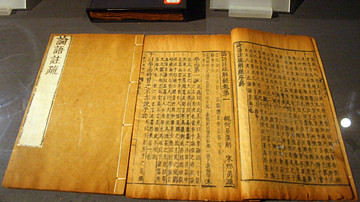

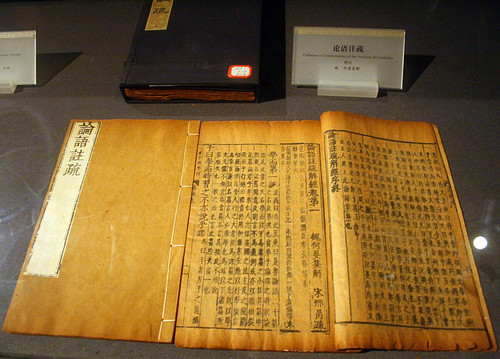

After a period of mourning which lasted the traditional three years, he set up his own school of philosophy where he taught Confucian precepts based on what would become known as the Four Books and Five Classics (minus his own work, of course, which was composed by his students):

- The Book of Rites (also known as The Book of Great Learning)

- The Doctrine of the Mean

- The Analects of Confucius

- The Works of Mencius

- The I-Ching

- The Classics of Poetry

- The Classics of Rites

- The Classics of History

- The Spring and Autumn Annals

Mencius claimed that Confucius had written, or at least edited all of the above (again, except for his own work) and this gave them greater authority and gravitas. Mencius' claim would go unchallenged until the 20th century CE. In the present, the Five Classics are attributed to authors of the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) and the Four Books to students of Confucius and Mencius.

Mencius' school focused on the moral improvement of his students and this included a thorough education in politics and what constituted an effective ruler. Scholar Forrest E. Baird comments:

The mainstay of Mencius' political philosophy was his insistence that the state function as a moral institution. The ruler must be a moral leader, a Gentleman, a sage-king, as were the great leaders of the past…The ruler must win the support of the people through benevolent ruling, because his right to rule stems not from the Mandate of Heaven alone; it stems equally from the consent of the governed. If the ruler fails to provide the people benevolent rule, he forfeits the Mandate of Heaven and his right to be called “king”. (293)

The Mandate of Heaven was a concept developed during the Zhou Dynasty which maintained that a king ruled by divine consent. The gods and the monarch entered into a contract where the ruler would care for the people, putting their interests above his own, and his dynasty would continue to rule as long as they followed suit. When it became apparent that a dynasty was no longer honoring their part of the contract, they were thought to have lost the mandate and were replaced. Mencius simply took this concept and developed it further.

As he lived in a time of continual chaos and war, he, like Plato in Greece, turned his attention to the hope of benefitting the rulers of the separate states by enlightening them through philosophy. He believed that if a ruler were a man of virtue, and led by example, then the people would aspire to that same kind of virtuous life and, further, would enjoy their days more fully in being governed justly.

Philosophy & Vision

Mencius' philosophy was formed by the era of the Warring States Period in which he lived. This period had earlier given birth to the so-called Hundred Schools of Thought which refers to the time when scholars and teachers, formerly employed by the government or attached to schools, found themselves unemployed, due to the political climate, and started their own schools, one of which was founded by Confucius.

The Warring States Period was a chaotic and savage era during which seven states fought each other for supremacy and control of the government. The Zhou Dynasty, which still ruled in name only, was too weak to do anything about the wars since the various states were all more powerful than the government. The philosophical schools arose, in large part, in response to the helplessness of the Zhou; if the government could do nothing to stop the violence then the philosophers would have to.

Confucianism held that people were essentially good, would naturally incline toward right than wrong, but needed a strong moral center and education to maintain their balance, control their self-interest, and live harmoniously with others. Confucius himself claimed that he never wrote anything new and developed no novel philosophy but only drew on the Five Classics of the Zhou Dynasty. By the time Confucianism reached Mencius, however, the school that had developed in the master's name was considered his creation. Mencius devoted himself to streamlining Confucian thought and making it more accessible to people.

Confucius maintained there were Five Constants and Four Virtues one should adhere to in order to live well and become a superior human being:

- Ren – benevolence

- Yi – righteousness

- Li – ritual

- Zhi – knowledge

- Xin – integrity

- Xiao – filial piety

- Zhong – loyalty

- Jie – contingency

- Yi – justice/righteousness

Mencius recognized the value of all nine but emphasized four virtues as essential:

- Ren – benevolence/humaneness

- Yi – righteousness/goodness

- Zhi – knowledge/wisdom

- Li – propriety/proper ritual

These are the famous Four Seeds of Mencius, so-called because he believed they were inherent in each individual and only needed proper nurture in order to sprout and bloom.

Mencius upheld the Confucian ideal that people were basically good and provided the best-known Confucian argument to support that claim. He noted that people's first inclination, when they find someone in trouble, is to help them and illustrated this with the example of a person coming upon a boy who has fallen into a well. The person's first inclination will be to save the boy – even though they do not know the boy or the boy's parents and even if the attempt poses a significant risk – and, if they themselves cannot rescue the boy, they will try to find someone else who can.

By this example, he highlighted the human inclination toward doing good which he interpreted to mean that goodness was a basic human quality. The inclination toward goodness could be blunted, however, by poor treatment by others and lack of opportunity to develop it through education; this produces bad people who do bad things. Conversely, educating people in the value of the Good, and in acting on good impulses, produces contented and helpful citizens.

This belief led to his initiatives to convert the monarchs of the separate states to Confucian ideals. If a ruler wished to truly govern wisely and securely, then, education of the people should be a priority. The kings, Mencius claimed, should set aside their petty differences and work for the good of the people by instituting educational programs, which would make the people good. This was Mencius' philosophy and vision, but it was only one of many, and others, including Confucius himself, had tried to nudge the warring states toward peace without success.

Contention with Other Schools

Besides Confucius, probably the most famous advocate for peace was Mo Ti, founder of the philosophical school of Mohism, which preached universal love and personal virtue. Confucianism emphasized filial piety and social hierarchy: one honored and respected one's social superiors, starting with one's parents and elders, and through the proper observance of rituals associated with this, one developed a good character and behaved well. Mo Ti argued that social classes should be abolished and everyone should love everyone else equally.

He also advanced the concept of consequentialism which maintained that behavior defined character and lived this by going to each of the separate states, often at great personal risk, to convince them to end the wars. As a skilled carpenter and craftsman, Mo Ti was in high demand for siege engines and fortifications but, in an effort to neutralize any state's advantage, he provided them all with exactly the same works. His efforts, he found, were futile and he eventually gave up.

Mencius admired Mo Ti for his advocacy and tactics but criticized him sharply for his insistence on universal love. As a Confucian, Mencius believed in the importance of social hierarchy and filial piety as foundational to order and stability, not just of the state, but on a personal level. He also criticized and condemned consequentialism, but it is unclear why, as Mencius advocated his own version of that same concept. Mencius believed that a good life is defined by one's own good behavior and this proper conduct would then inspire the same in others; almost exactly what Mo Ti claimed.

He also had harsh words for the hedonist philosophy of Yang Zhu (l. 440-360 BCE) who believed the pursuit of pleasure was the only appropriate response to life and any philosophies or religious beliefs were simply delusional wastes of one's time. Mencius argued that Yang's school of thought (which came to be known as Yangism) was a dangerous threat to society as well as one's personal morality and condemned it as subversive.

Like the philosophers Lao Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE) and Teng Shih (l. c. 500 BCE), Mencius believed that “men are by nature good and that the social problem arises not out of the nature of men but out of the wickedness of governments” (Durant, 684). Unlike those philosophers, however, who believed that fewer laws were better than strict adherence to ritual, Mencius was an advocate of government, law, social hierarchy, and the other precepts of Confucius, and felt that the best government would be one administrated by the ideals, put into policy, of Confucian philosophers.

Years of Travel, Retirement, & Death

To that end, Mencius set out with a few of his students to try to convince the various kings of the value of Confucian thought and practice. Traveling from one state to another, for almost 40 years, Mencius attempted to teach his precepts by example and also through lectures. He appealed to the generally accepted understanding of Confucian philosophy, which was of course known by this time, and also to historical precedent of peace understood as far more beneficial to a state than war. Unfortunately, none of the rulers were interested in being the first of the states to lay down arms and practice the benevolence Mencius advocated. Durant writes:

Like the men invited to an ancient wedding feast, the various princes had many excuses for not being rectified. "I have an infirmity," said one of them. "I love valor." "I have an infirmity," said another. "I love wealth." (683)

Each monarch had an excuse as to why they could not adopt Confucianism and why they would not end the wars. Still, like Mo Ti, Mencius persevered until he recognized he could not change men's hearts against their will. He then devoted himself exclusively to the betterment of the students of his private school. Upon his death, they raised a great monument over his grave in an expression of their devotion to the man who had been like a father to them.

Conclusion

Mencius' major contributions to Confucian thought are the developments of the inherent goodness of human beings, the Four Seeds concept, adherence to the Confucian 'silver rule' – "whatsoever you do not want done to you, do not do that to another" – and the establishment of a moral and benevolent government which would encourage its citizens to pursue virtue over vice.

His attempts to convince the kings and princes of the Warring States Period to adopt his philosophy failed because his precepts were rejected as too idealistic. Mencius advocated for the equal distribution of land among the people, fair taxes, a pension and care for the aged, and educational programs for the improvement of the people's moral character. None of the kings who were waging war for complete control of the country were interested in any of these policies.

Mencius' vision was tempered later by the last of the Five Great Sages, Xunzi. Xunzi completed the development of Confucian thought by presenting an opposing view to Mencius' idealism. Xunzi argued that human beings are not good by nature and must be taught goodness as evidenced by the many different philosophies which had developed toward that end. If human beings were innately good, he argued, they would not need to be instructed in goodness.

The Warring States Period ended with the state of Qin defeating the others through a brutal policy of total war. They then founded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) which adopted the philosophy of Legalism which claimed humans were innately self-centered and selfish and had to be controlled by strict laws and rules. Between 213-210 BCE, the Qin Dynasty burned the books of other philosophical schools including, of course, Confucianism.

When the Qin Dynasty fell to the Han Dynasty, Confucianism and the other schools were revived. The views of Xunzi, considered more 'realistic' than those of Mencius, combined with his to temper the overall vision of Confucianism which would be adopted by the Han as the state philosophy under Wu the Great (r. 141-87 BCE). Since that time, more or less, Confucianism – as understood through the lens of Mencius' work primarily – has informed Chinese culture and the philosophy, as it is understood in the present day, is as much the work of Mencius as of its founder.