The government of ancient Persia was based on an efficient bureaucracy which combined the centralization of power with the decentralization of administration. The Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) founded by Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE) is sometimes claimed to have invented this form of government but actually drew on earlier models of Akkadian and Assyrian administration.

The Achaemenid model would be followed by successive empires in the region – the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE), Parthia (247 BCE-224 CE), and the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) – with little modification because it was so effective. The government was a hierarchy with the emperor at the top, administrative officials and advisors just below him, and secretaries below them. The empire was divided into provinces (satrapies) administered by a Persian governor (satrap) who was responsible only for civil matters; military matters in a satrapy were handled by a general. This system prevented any satrap from raising a rebellion because he had no access to the military and discouraged the same by a military leader because he lacked private funds to entice troops to rebel.

This form of government remained in use from c. 550 BCE through 651 CE, again with little modification, until the Sassanian Empire fell to the Muslim Arabs in the 7th century CE. It was the most effective model of government in the ancient world, influencing the form of government adopted by the Roman Empire, and its basic model is still in use in the present day.

Early Models

The concept of centralized power administered through trusted officials was developed by Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE) after he established the Akkadian Empire (2334-2083 BCE), the first multi-cultural empire in the world. Sargon selected his administrators from those he felt he could trust (known as “Citizens of Akkad”) and granted them power to govern in the over 65 cities which made up his empire.

He also made use of the power of religion, placing his daughter, Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE) in the position of High Priestess of Ur in Sumer to encourage piety and adherence to the established order. Although Enheduanna is the only known example of such positioning, it is likely Sargon did the same in the temples of other cities.

The governors of each city were supervised by Sargon's agents who would make surprise visits to ensure their loyalty and efficient use of resources. Sargon's initiatives created a stable environment, which allowed for the development of a strong infrastructure of roads, improvements to cities, and a postal system.

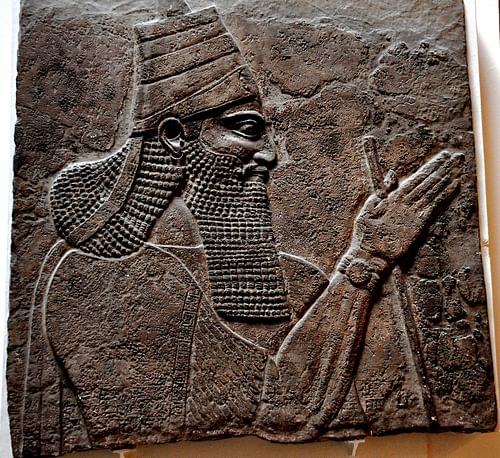

Sargon and his successors became legendary in Mesopotamia long after their empire fell and the Akkadian model was reformed by the Assyrian king Tiglath Pileser III (r. 745-727 BCE) of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Tiglath Pileser III (birth name Pulu) was the provincial governor of the city of Kahlu (also known as Nimrud) under the reign of Ashur Nirari V (r. 755-745 BCE). Provincial governors were responsible for administering the monarch's decrees but, increasingly, acted autonomously in their own interests, and Ashur Nirari V made no move to stop this. By 746 BCE, dissatisfaction with Ashur Nirari V's negligence resulted in a civil war – possibly initiated by Pulu, though this is unclear – pitting the factions of the provincial governors against the ruling house. Pulu killed Ashur Nirari V and his family in a coup, seizing power and taking the throne name of Tiglath Pileser III.

His first order of business afterwards was to make sure he would not someday experience the same sort of coup. He cut the size of provinces in half, increasing their number from 12 to 25 so that the smaller regions would not be able to muster as many men in arms as before. He then reduced the power of provincial governors, placing two men in power over each province each of whom had to agree on policy decisions before they could be enacted and, further, he made these governors eunuchs so that there was no chance of a governor making a power-grab in order to establish a family dynasty.

With this system in place, he then borrowed from the Akkadian model and established an intelligence network by which trusted administrators would visit the provinces unannounced to make sure everything was running as he wished. Tiglath Pileser's model would serve the Neo-Assyrian Empire well until its fall in 612 BCE to a coalition led by the Medes and Babylonians.

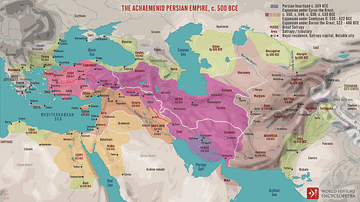

Achaemenid Government

The Medes became the dominant power in the region until they were overthrown by Cyrus the Great c. 550 BCE and were the civilization which had earlier adopted the satrapy system used by the Assyrians. The Medes kept the system more or less intact and it was this model Cyrus drew on for his own while modifying the model of the Assyrians. Herodotus notes how “the Persians adopt more foreign customs than anyone else” (I.135) and this was certainly true of Cyrus in forming his government. Both the Akkadian and Assyrian empires ruled over diverse people across vast regions, and while initially successful, both had fallen. In an effort to prevent that from happening to his own creation, Cyrus took the best aspects of the earlier governments and ignored those which caused the most problems.

One of the most hated policies of the Assyrian Empire was the practice of deportation and relocation of large populations. The decision of the Assyrians to relocate people was not made hastily or harshly – families were kept together and people were chosen for their particular talents and skills – even so, this was no consolation to those uprooted from their homes and transported to some foreign region. Other unpopular Assyrian policies were the practice of making anyone conquered (who was not then sold into slavery) an “Assyrian” as an integral part of the empire and also the proliferation of temples to the supreme Assyrian god Ashur throughout conquered regions. In 612 BCE, when the Median-Babylonian coalition destroyed the cities of Assyria, they paid special attention to temples and statues of the gods and kings they had come to hate.

It has been argued that Cyrus was a Zoroastrian based on the religion having developed in the region c. 1500-1000 BCE and references to the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda associated with Cyrus. Ahura Mazda was already the supreme god of the ancient Iranian pantheon, however, long before the prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra) received his vision. Whatever Cyrus' personal beliefs, he did not force them on anyone else. Everyone in the empire was free to worship whatever god they pleased in any way they wanted to.

Cyrus famously freed the Jews from the so-called Babylonian Captivity and even helped fund the rebuilding of their temple in Jerusalem. Any conquered people were allowed to remain where they had always lived, doing whatever they had always done, and all Cyrus asked was that taxes were paid, men were provided for the armies, and everyone should try to get along with each other as best they could.

His government was based on his supreme central rule enacted by the decentralized satrapies who, as with the Assyrian system, were checked up on by Cyrus' officials - the eyes and ears of the king. There are no recorded revolts during the reign of Cyrus the Great and a testament to his success as empire-builder and ruler is how he was addressed by the people who referred to him as their father.

After Cyrus' death in 530 BCE, his son Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE) extended the empire into Egypt and continued the same policies. Cambyses II is often portrayed as an unbalanced and inefficient monarch, but this is most likely because he made so many literate enemies among the Egyptians and Greeks. He does seem, however, to have pursued harsher policies than either his father or his successor Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE). One example of this is his reaction to the royal judge Sisamnes accepting a bribe. According to Herodotus:

Cambyses slit his throat and flayed off all his skin. He had thongs made out of the flayed string and he strung the chair on which Sisamnes had used to sit to deliver his verdicts with these thongs. Then he appointed Sisamnes' son to be judge instead of the father whom he had killed and flayed and told him to bear in mind the nature of the chair on which he would sit to deliver his verdicts. (V.25)

When Darius the Great came to power, he instituted a new paradigm through his law code known as the Ordinance of Good Regulations. This work only exists now in fragments and citations from later writers but seems to have been based on the earlier Code of Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE). One of Darius I's stipulations was that “no one, not even the king, can execute anyone who has been accused of only a single crime…but if after due consideration he finds that the crimes committed outweigh in number and gravity the services rendered, then he can give way to anger” (Herodotus I.137).

When a royal judge named Sandoces was found guilty of taking a bribe, Darius I ordered him crucified. After considering his own law, however, he recognized that the good Sandoces had done as judge outweighed his single crime of accepting the bribe and so he was pardoned though, instead of returning to his former position, he was made a provincial governor (Herodotus I.194).

Darius I divided the empire into seven regions:

- Central Region: Persis

- Western Region: Media and Elam

- The Iranian Plateau: Parthia, Aria, Bactria, Sogdiana, Chorasmia, and Drangiana

- The Borderlands: Archosia, Sattagydia, Gandara, Sind, and Eastern Scythia

- The Western Lowlands: Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, and Egypt

- The Northwestern Region: Armenia, Cappadocia, Lydia, Overseas Scythians, Skudra, and Petasos-Wearing Greeks

- The Southern Coastal Regions: Libya, Ethiopia, Maka, and Caria

Each of these regions was then further divided into twenty satrapies. To make sure the satraps were performing their duties honestly, Darius I kept Cyrus the Great's earlier system which was now refined for the smaller satrapies. He placed a Royal Secretary in each province who would assist the satrap but report to Darius. There was also a Royal Treasurer who oversaw government expenditure, approved whatever projects the satrap needed money for, and also reported to Darius. The dual-responsibility of satrap and military commander remained the same with a Garrison Commander in charge of a province's armed forces but no access to the treasury.

Darius also kept the practice of “trusted men” who would appear without notice to check up on each province. These were known as the Royal Inspectors whose principal responsibility was to make sure government officials were performing their duties honestly but there was also a committee of trusted men who assessed taxes in the region and registered citizens to make sure that taxes were being levied fairly by the satrap and that all taxes were going where they should.

Seleucid & Parthian Governments

Darius I's successors continued these policies although none of the later monarchs were as effective as he had been. When the Achaemenid Empire fell to Alexander the Great in 330 BCE, it was replaced by the Seleucid Empire founded by one of Alexander's generals, Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE). Seleucus I kept the Achaemenid model of government intact but placed Greeks in positions of power throughout the provinces. This policy caused resentment, and after Seleucus I's death, his successors had to deal with numerous rebellions.

Among the people who rebelled were the Parthians in 247 BCE. Their first king, Arsaces I of Parthia (r. 247-217 BCE) also kept the Achaemenid model and was so busy establishing his empire at the Seleucids' expense that he made little revision to it. His successors, however, would make significant changes. The empire was divided into Upper Parthia (Parthia and Armenia) and Lower Parthia (Babylonia, Persis, Elymais).

These five regions were divided into provinces but were not always administered by a Parthian official. The Parthians favored keeping client kings on their thrones in order to encourage a sense of continuity in the provinces and loyalty of the provincial monarch to the empire.

This policy did not always work so well, however, as the client kings were apt to seize on any perceived weakness of the central government and advance themselves through alliances with enemies of the state – which, in Parthia's case, was increasingly the Roman Empire. It was not Rome that brought down the Parthian Empire, however, but the vassal king Ardashir I (r. 224-240 CE) who founded the Sassanian Empire.

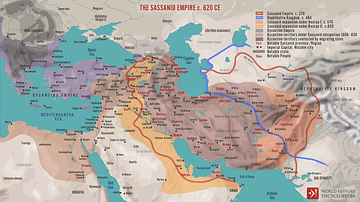

Sassanian Government

The Parthian system of government resulted in a much looser administration than the Achaemenid model. The five regions, sometimes governed by client kings and sometimes by officials picked by the court, were not as cohesive an entity and lacked the failsafe Darius I had made integral to running an empire. After Ardashir I overthrew the last Parthian king Artabanus IV (r. 213-224 CE), he embarked on a series of military campaigns to tighten control over Parthian lands and centralize the government.

Ardashir I was a devout Zoroastrian and founded his vision of government on the Five Principles of the religion:

- The supreme god is Ahura Mazda

- Ahura Mazda is all-good

- His eternal opponent, Ahriman (also Angra Mainyu), is all-evil

- Goodness is apparent through good thoughts, good words, and good deeds

- Each individual has free will to choose between good and evil

After Ardashir united the former Parthian Empire under his rule (and expanded it), he followed the same example as his predecessors in adopting the Achaemenid model of government only now the government officials were expected to honor Zoroastrian beliefs and practices. This is not to say Zoroastrianism never played a part in Persian government before the Sassanians. Xerxes I (486-465 BCE) and other Achaemenid kings were practicing Zoroastrians, but they never made the faith part of their political platform.

Zoroastrianism informed the Sassanian government and became the state religion, but this did not mean that people of other faiths were excluded from public service or persecuted under Ardashir I or his son and successor Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE). Shapur I, in fact, welcomed people of all faiths into the empire and allowed Jews and Buddhists to build temples and Christians to erect churches. Shapur I saw himself as an embodiment of the holy warrior king advancing the truth of Zoroastrianism against the forces of darkness and evil epitomized by the Roman Empire. Shapur I was almost universally successful in his engagements against Rome and became a model for his successors.

The religious tolerance of the Sassanian Empire was continued until the reign of Shapur II (309-379 CE) who saw Christianity as a Roman faith, which sought to subvert the truth of Zoroastrianism. Under Shapur II's reign, the Avesta (Zoroastrian sacred work) was committed to writing and Christians were persecuted throughout the empire. Religious tolerance continued to be extended to those of other faiths not associated with Rome and so Shapur II's persecutions are regarded as more of a political than religiously-motivated policy.

The persecutions did not last beyond his reign and his successor, Ardashir II (r. 379-383 CE), reinstituted the earlier policy of acceptance of all faiths. The greatest of the Sassanian kings was Kosrau I (also known as Anushirvan the Just, r. 531-579 CE) who returned the Sassanian Empire to the early vision of Ardashir I and Shapur I but with a greater focus on education and cultural refinement.

Conclusion

Kosrau I's successors maintained the model of government even though, in the early 7th century CE, the empire was periodically decentralized as nobles asserted themselves in different regions. The Sassanian Empire fell when it was conquered by the invading Muslim Arabs in 651 CE who also applied the basics of Achaemenid government to their territories in that one ruler (a shah) decreed the law which was then implemented by satraps. Under Muslim rule, however, non-Muslims would eventually be required to pay a tax to live among them and the policy of religious tolerance was discarded in favor of conversion.

The Achaemenid Persian model of government became the standard for rule in Central Asia through Mesopotamia from c. 550 BCE through 651 CE, allowing for the development of one of the richest cultures in the world. As noted, the Persian model influenced that of the Roman Empire, which would further impact later cultures right up to the present-day example of the United States of America whose governmental paradigm is based on Rome's.

The only serious flaw in the model was that an individual ruler was never fully secure in his position because kingship was thought to be conferred by the gods or a single god, Ahura Mazda. A court noble or satrap who mounted a successful revolt would be considered chosen by divine forces for rule while the deposed would have simply deserved his fate.

Even so, it is clear that a number of monarchs in each of the different empires seem to have been genuinely favored by the nobility and common people, primarily because of benefits given like reduced taxes. This same paradigm is seen today around the world in governments whose people favor a leader only as long as it benefits them personally. Basic human motivation has not changed since recorded time and there have been many different forms of government to try to manage and channel it positively. Among these is the Persian model which served the ancient empires well for over a thousand years and whose influence continues to be felt in the modern era.