Persian Literature differs from the common definition of “literature” in that it is not confined to lyrical compositions, to poetry or imaginative prose, because the central elements of these appear, to greater or lesser degrees, in all the written works of the Persians.

Histories or medical treatises, religious texts or philosophical commentary are considered “literature” – in the artistic sense – as much as any poem or fictional tale. Poetry was regarded as the highest form of artistic expression by the ancient and medieval Persians and so informs any other medium.

The first evidence of Persian literature is usually dated to c. 522 BCE with the creation of the Behistun Inscription of Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE) but, at the same time, scholars generally agree that there is no “Persian literature” prior to the period of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) because earlier works (except for certain inscriptions and administration records) were lost. Alexander the Great destroyed the library at Persepolis c. 330 BCE and other works, not inscribed on baked clay tablets, were lost in later times of upheaval and conquest. Persian literature is therefore commonly dated from c. 750 CE, with the rise of the Abbasid Dynasty, through the 15th century CE and earlier works, for the most part, can therefore only be referred to as “ancient” in that many medieval poets preserved stories and themes from pre-Islamic Iran.

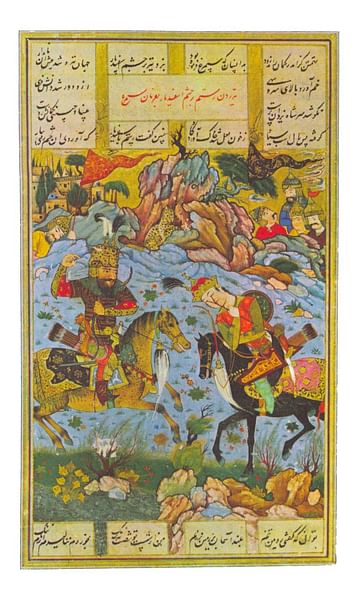

The literature of Persia is among the oldest in the world, spanning thousands of years, and has influenced the literary works of many other cultures. The greatest and most influential work is the Shahnameh – the Persian Book of Kings – written by the poet Abolqasem Ferdowsi between 977-1010 CE. The Shahnameh epitomizes the spirit of Persian literature, up through the present day, in that it preserves the ancient stories of the past while keeping them relevant for every new generation who reads them. The same spirit of preservation and novelty characterizing Ferdowsi's work is recognized in the artistic efforts of modern-day Persian poets who also continue their predecessors' emphasis on love as the most important aspect of the human condition.

Literary Development in Persian Empires

The Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE), founded by Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE), was the first large-scale Persian political entity in the world. Cyrus was succeeded by his son Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE) who was afterwards succeeded by Darius I. Darius I's ascension was challenged by a number of Persian governors (satraps) who claimed he had usurped the throne in assassinating the legitimate successor, Bardiya (r. 522 BCE briefly) but Darius I claimed that this man was an imposter, a magi (priest) named Gaumata who had managed to impersonate Bardiya and deceive the people.

Once Darius I had put down the revolts and established order, he had an inscription carved high on the cliffs above a main thoroughfare telling this story – known today as the Behistun Inscription – which is recognized as the first instance of Persian literature because it can be regarded as history or fiction. The Behistun Inscription relates how Darius I, with the approval and assistance of the god Ahura Mazda, overthrew the usurper Gaumata – and then his supporters – to establish order in the land. Whether this account is factually true cannot be determined, but many modern scholars (among them the well-known A. T. Olmstead) claim that Darius I was the actual usurper and Bardiya/Gaumata the legitimate king based on the records of the time which provide no evidence of social unrest under Bardiya/Gaumata but widespread revolt when Darius I took the throne.

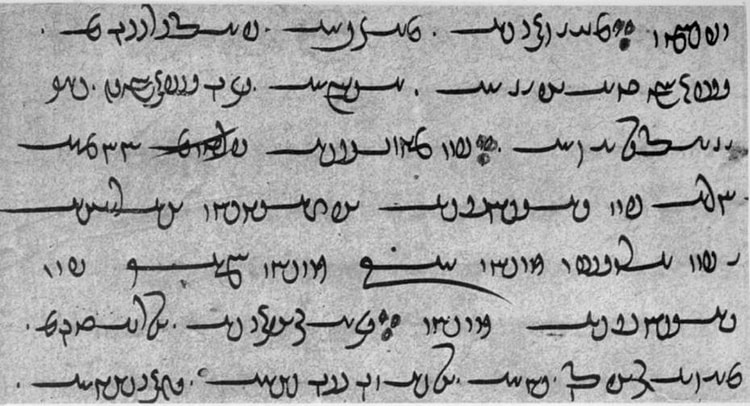

Whatever else may have been written during the Achaemenid period was lost during the campaigns of Alexander the Great, culminating in the tragic loss of the library at the capital city of Persepolis when Alexander burned it in 330 BCE. The political and cultural progress of Persia was interrupted afterwards by the establishment of the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE) founded by one of Alexander's generals, Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE). When the Seleucid Empire fell, it was succeeded by the Parthian Empire (247 BCE - 224 CE) which adopted Aramaic as their language, written in an Aramaic script which came to be known as Arsacid Pahlavi. Commentaries on the Avesta, the Zoroastrian scriptures which had been passed down orally since before the Achaemenid Empire, were written in this script but there is no evidence of further literary developments.

It was not until the Sassanian Empire, therefore, that Persian literature started to develop to any significant degree. The first king, Ardashir I (r. 224-240 CE), whose father and grandfather had both been priests and who therefore came from an educated family, encouraged literary development through his efforts to have the Avesta committed to writing. Ardashir I's efforts, which would be fully embraced by his son Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE), mark the beginning of written Persian literature.

Literary Development & Poetry

There are a number of modern-day scholars who claim that Ardashir I, and his successors, were essentially “inventing” Persian literature because they could not have had any significant knowledge of the literature of the Achaemenid Empire as it had fallen some 500 years earlier and left few written records other than administrative documents inscribed on clay tablets. This view is untenable as it ignores a central aspect of Persian culture: the importance of the oral tradition of storytelling.

Persian religious texts – and any other type – rely on a diachronic method of relaying information, best defined by the scholar Norman F. Cantor as “tell me a story” (17). When faced with some existential question, the Persians – like many other ancient or medieval cultures – responded by telling a story that explained the phenomenon. It did not matter whether this story was, factually, “true” – it only mattered how well it served to answer the question. By the time of the Sassanian Empire, there was a long history of the diachronic tradition which took the form of folklore, legend, and religious revelation. Ardashir I and his successors drew on this oral history to commit the Avesta to written form and, from this effort, Persian literature developed and, most prominently, in the form of poetry.

Middle Persian Literature & Conquest

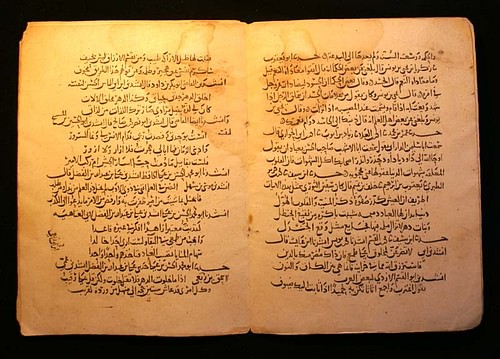

This poetry – at least what has survived – did not take the form of recognizable poetic works in set verse but informed the written religious works of the period. This literature was written in Middle Persian, the prestige dialect of the ruling house of the Sassanian Empire. Drawing on the script developed by the Parthians, the Sassanians developed so-called Book Pahlavi script in composing commentaries on the Avesta as well as other compositions on non-religious topics.

Before that winter, those fields would bear plenty of grass for cattle: now with floods that stream, with snows that melt, it will seem a happy land in the world, the land wherein footprints even of sheep may still be seen…

There thou shalt make waters flow in a bed [a mile] long; there thou shalt settle birds, by the ever-green banks that bear never-failing food. There thou shalt establish dwelling places, consisting of a house with a balcony, a courtyard, and a gallery. (Fargard II.24 and 26)

The extant texts of Middle Persian works come primarily from the 6th and 7th centuries CE, inspired by great Sassanian rulers such as Kosrau I (r. 531-579 CE) and continued, however unevenly, by his successors. The last monarch of the Sassanian Empire, Yazdegerd III (r. 632-651 CE) was too preoccupied in trying to stave off the invasion of his lands by the Muslim Arabs to devote any time to literary development but it seems Sassanian scribes were still at work on manuscripts when the empire fell to the Muslims in 651 CE.

In an effort to dominate the Persian culture, the conquerors destroyed libraries, temples, and other centers of learning, resulting in the loss of countless manuscripts which were not either hidden or carried out of the region. The Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE) was especially oppressive in terms of Persian culture but the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258 CE) was far more lenient, eventually adopting and then encouraging Persian customs at court and the revival of interest in a pre-Islamic Persian past. The poetic nature of the oral Persian literary tradition inclined itself especially to the more mystical concepts of Islamic theology and came to inform Muslim compositions on these themes. So-called “Muslim literature”, therefore, frequently draws on much earlier Persian concepts and modes of expression.

The Samanid Dynasty, Poetry, & the Shahnameh

Written Persian literature from the medieval period is informed by the same ancient oral tradition and found full expression during the Samanid Dynasty (819-999 CE), also known as the Samanid Empire, a political entity which flourished under Abbasid rule. Scholar Homa Katouzian comments:

It was under the Samanids that Persian literature and culture began to flourish, the foundations of classical Persian literature were laid, and Persian science experienced a period of glory. (84)

Katouzian notes that Samanid support and encouragement of Persian literature led later historians and commentators to conclude that they were “modern Iranian nationalists” trying to “shake off Arab rule and culture by promoting Persian language and literature” but how this claim ignores the actual nature of the Samanid Dynasty as Sunni Muslims, loyal to the Abbasid Caliphate, who encouraged Arabian Muslim literature at the same time, and with the same enthusiasm (84). A clearer interpretation of the Samanid support for Persian literature is simply that, by the time they were in power, Persian culture and language had come to influence and then inform the Abbasid court and this respectability encouraged interest and development of Persian literature.

The greatest of the Persian poets under the Samanids – referred to as “the father of Persian literature” and “the founder of classical Persian poetry” – was Rudaki (l. 859 - c. 940 CE) who is said to have been able to write in every literary form. Rudaki essentially created written Persian literature by establishing poetic forms as well as the means of transmission: the diwan (also given as divan), a collection of the shorter works of a given author, which would later become standard.

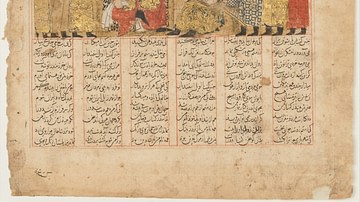

Following Rudaki, Persian literature was developed by the great poets who came after him and is exemplified in the literary masterpiece of the Shahnameh (the Persian Book of Kings) by Abolqasem Ferdowsi (l. c. 940-1020 CE). The Shahnameh was Ferdowsi's life's work, thought to have been composed between 977-1010 CE. It is a poem of some 50,000 rhymed couplets which tells the story of the mythological/legendary history of Iran and the Persians from the creation of the world up through the time of the Muslim Arab conquest. It is considered one of the greatest literary works in the world and remains popular in the present day.

Poetic phrasing was not restricted to the creation of imaginative verse, however, but informed all kinds of written works. The Persian polymaths Avicenna (l. c. 980-1037 CE) and Averroes (l. 1126-1198 CE) both wrote their scientific, medical, mathematical, and other works in verse.

Poets & the Message of Love

As noted, poetry also informs Persian prose histories, religious commentary, criticism, and biographies, as well as translations of works from other languages. The poetic form, however – what one would understand as “poetry” – was always considered the highest form of expression and reached its height in the 12th-15th centuries CE through the works of Persian poets drawing on the traditions and symbols of Sufism (the mystical approach to the practice of Islam) and the power of Divine and human love to give meaning to one's life.

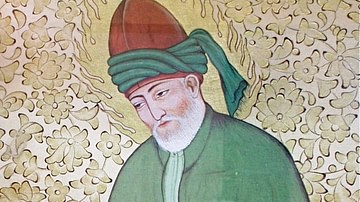

These poets are among the best-known in the West and include Sanai (l. 1080-c.1131) who would influence - among many others - the poets Attar of Nishapur (l. c. 1145-c.1220 CE) and the great Rumi (l. 1207-1273 CE) whose popularity in the present day attests to the enduring human truths he so eloquently expressed. Other poets who continue to be highly regarded are Saadi (l. 1210 - c. 1291 CE), best known for his book Bustan (“The Orchard”) and Nizami (l. c. 1141-1209 CE) whose Khamsa (“Quintet”) was equally popular and influential. Among the best-known Persian poets in the West – and easily the most popular throughout the 20th century CE – is Omar Khayyam (l. 1048-1131 CE) whose Rubaiyat – in the English version by the poet Edward Fitzgerald – remains among the most oft-quoted works in world literature even though, in Persian tradition, Khayyam is regarded as a great scientist and mathematician and only a minor poet.

The greatest artist of the Persian poetic tradition is considered Hafez Shiraz (also given as Hafez and Hafiz Shiraz, l. 1315-1390 CE) who combined the literary developments of the past with his own insight to produce some of the most memorable and evocative works not only in Persian but in world literature. Although many of Hafez's symbols and literary conceits were once considered original (as is also the case with Rumi), they were used earlier by Rudaki and those who came after him. Hafez's poem Now is the Time, for example, begins with the lines:

Now is the time to know

That all that you do is sacred.

Now, why not consider

A lasting truce with yourself and God?

Now is the time to understand

That all your ideas of right and wrong

Were just a child's training wheels

To be laid aside

When you can finally live

With veracity and love. (Abhay K., 1)

The poet here encourages an honest assessment of one's self, not bound by religious, cultural, or familial traditions, in recognizing the Divine, characterized as Love. Similar themes were addressed by Rudaki who emphasizes the importance of love over ritual in the lines:

What God accepts from you are love's transports

But prayers said by rote He won't admit. (Lewisohn, 77)

Rumi also explores the theme of transcendent love in depth in many of his poems, emphasizing the necessity of moving beyond the known and accepted world – including religious strictures – to experience the ultimate reality of love. His poem, The Gift of Water, concludes with the lines:

You knock at the door of reality,

Shake your thought-wings, loosen

Your shoulders,

And open. (Barks, 200)

Being open to love, in all its forms, is a central message of Persian literature no matter what form of expression it takes. In Hafez's works, this theme is thought by many scholars to be developed most eloquently with the highest degree of artistry, giving him the honor of being named the greatest Persian poet. Hafez himself, however, would no doubt credit those who came before him who responded to questions about the world by answering in verse. In doing so, they developed a body of literature which, in keeping with the great literary traditions of cultures around the world, assures readers that they are not alone in either their hopes or fears and that the final answer to life's questions is love.