Rochester Castle, located in Kent, England, was first constructed shortly after 1066 CE by the Normans, was converted into stone between 1087 and 1089 CE, and then added to over subsequent centuries, notably between 1127 and 1136 CE, and again in the mid-14th century CE. The imposing castle keep or donjon seen today was added in the 12th century CE and is one of the best-preserved and tallest of any medieval castle. Odo of Bayeux, half-brother of William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087 CE), was a famous resident as well as the bishops of Rochester. In 1215 CE Rochester was the scene of a major siege by King John of England (r. 1199-1216 CE) when rebel barons temporarily took over the castle. Today the site is managed by English Heritage and is an important surviving example of 12th-century CE castle architecture.

Early History

Rochester Castle is located in the English town of that name in the county of Kent, southern England, some 40 kilometres (25 miles) east of London. The castle lies on the banks of the River Medway, strategically located next to the medieval bridge which crossed the river and so directly on the route between London and Canterbury and Dover.

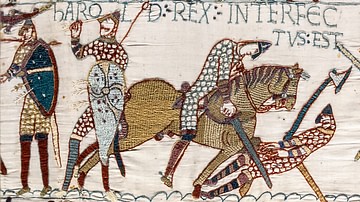

Rochester castle was first built shortly after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 CE and the subsequent Norman conquest of England and is mentioned in Domesday Book (1086-7 CE). The land on which it was built was acquired from the Bishop of Rochester in exchange for land in Aylesford, Kent. This largely wooden structure, likely a motte and bailey castle, included a curtain wall and dry moat.

The castle came into the hands of Odo of Bayeux (d. 1097 CE) who was the bishop of Bayeux in Normandy and the half-brother of William the Conqueror. Made the Earl of Kent and second most powerful man in England after the king, Odo used Rochester castle as one of his many bases - mighty Dover Castle was another of his residences. The rapacious Odo fell out with his half-brother for a time, and when William's son William II Rufus, inherited the throne (r. 1087-1100 CE), the new king had no time whatsoever for his scheming uncle, and Odo lost his castle at Rochester to a siege. Shortly after, the castle was then rebuilt in stone between 1087 and 1089 CE (the precise dates are not known), under the orders of Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester (appointed 1077 CE), for its new owner, William Rufus. Gundulf also had the cathedral rebuilt just next door to the castle, using Canterbury as a model, and he is credited with having a hand in the building of the White Tower of the Tower of London.

In 1127 CE Rochester castle was granted to the bishops of Rochester in perpetuity by Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135 CE). The keep seen today was then added under the auspices of the Archbishop, William of Corbeil, between 1127 and 1136 CE. Around 1172 CE Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189 CE) further improved the castle, spending the significant sum of 100 pounds on the project. King John was the next monarch to significantly invest in the castle, spending 115 pounds on upgrades in 1206 CE. Unfortunately for the king, the money was rather wasted as he then had to lay siege to his own castle in 1215 CE (see below).

Curtain Walls

As was typical of medieval castles, Rochester had a curtain or bailey wall. This no longer survives today except in sections, but the walls were originally an impressive 6.7 metres (22 ft.) high and 1.37 metres (4.5 ft.) thick at the base. Some small stretches of the castle's original 11th-century CE crenellated outer wall remain on the riverside, some of which were built on top of the city's ancient Roman walls. In the 13th and 14th century CE sections of the wall were rebuilt on the southeast and eastern sides of the castle; some parts of these are still visible today as the back walls of gardens belonging to housing in Rochester's High Street. Gundulf added a tower into the eastern side of the curtain walls and the foundations of this were built upon to create a new tower, one of two added in the 14th century CE. As with the Norman original, the later versions of the castle were surrounded by a wide dry moat.

The Castle Keep

Between 1127 and 1136 CE, then, a massive rectangular keep was added in the south corner of the complex. The material used was Kentish rag and dressed stones from Caen in Normandy. The tower, with three floors and a basement, was 34.4 metres (113 ft.) high with smaller corner towers rising above the wall walk by another 3.7 metres (12 ft.). The walls were made especially thick to resist stone missiles, some 3.7 metres thick at the base and tapering to a still-impressive 3 metres (10 ft.) at the top. The thickness allowed for many mural chambers and galleries to be cut into them in the interior at the higher levels. The tower was further strengthened by a massive internal cross-wall, dividing the keep in half from top to bottom. The interior rectangular floor space measured some 14 metres (46 ft.) x 6.4 metres (20 ft.).

For extra protection, the foundations were made extremely deep to deter undermining, there was a drawbridge, and a massive staircase entrance to the first floor of the tower which was entirely enclosed in a fore-building and tower on the north face. The main doorway was protected by a portcullis - its wall grooves are still clearly visible today. The staircase entrance seen today is modern, but it was built on the original entrance ramp. The keep at Rochester had wooden hoardings around the top to act as covered and overhanging firing platforms, as indicated by the presence of holes for beams in the stonework just below the crenellations.

Today, the floors and ceilings are no longer present within the tower following a fire of unknown date, but the impressive windows and arcades are still a reminder of its past grandeur. Spiral staircases in the northeast and southwest corners provided access between floors. Unusually, the tower had the castle's second chapel on the top floor (the other being in the fore-building), a reflection perhaps of its status as a bishop's residence. The middle floor had sumptuous private apartments, and these were given grandeur by ornate, carved decoration on the windows, doorways, and fireplaces, and by making the central cross-wall on this floor a columned arcade. The tower had its own well as a protection against a siege, the door can be seen at the base of a covered shaft which rises to the top of the structure within the central cross-wall, allowing each floor to access water using a rope and bucket. The well itself was cut down 18 metres (59 ft.) into the bedrock and the top half of it then lined in stone.

The Great Hall was likely on the first floor of the keep as suggested by the presence of several grand fireplaces. This hall would have hosted audiences with the archbishop, receptions, and impressive feasts. One inventory for supplies in 1266 CE, when the castle was the residence of Roger Leyburn, includes 251 herrings, 50 sheep, 51 salted pigs, and quantities of rice, figs, and raisins. Goods came to the castle from far and wide: fish from Northfleet, oats from Leeds, rye from Colchester, and wine from specialised dealers in London.

The Siege of King John

Rochester castle saw its greatest crisis in 1215 CE as it became the pawn in a complex game of kings, archbishops, and barons. In June 1215 CE the castle had been given to Stephen Langton, the Archbishop of Canterbury, but then in August of the same year ownership was transferred to Peter des Roches, the Archbishop of Winchester, a friend of King John. Then, in September, a group of rebel barons led by William de Albini claimed to be acting in the name of the castle's constable, Reginald de Cornhill (an opponent of the king) and seized control of it. King John, then in Dover, reacted swiftly and, leading his troops in person, besieged the castle from 11 October, taking the bridge across the Medway and so isolating the castle from reinforcements. The defenders did not have a great quantity of supplies but they did have the castle's garrison which numbered between 95 and 140 men (the medieval chroniclers do not agree), including a contingent of knights and crossbowmen.

Unfortunately for the rebels, King John organised a constant barrage, day and night, of heavy missiles from five large catapults and rotating units of archers and crossbowmen. The defenders became low on food and were forced to eat their own horses. The combination of catapults and tunnelling eventually did their job and so the attackers pierced the outer wall, allowing the king's men to approach the keep. Sappers were then instructed to mine under a corner of the keep, which they did. Next, props in the tunnel and quantities of flammable pig fat and wood were set ablaze causing the collapse of the tunnel and also the partial collapse of the southeast corner of the tower above. However, the defenders did not give up and continued to resist safe behind the cross-wall. Without food, though, they could not survive indefinitely and were obliged to surrender on 30 November.

The badly damaged tower was rebuilt with a new rounded corner section, and this is the form that can be seen today. The keep was further protected by the construction of a protective wall in front of it. Other additions after the siege included better fortifying the southern gate and, around 1225 CE, an extension and deepening of the moat, which then enclosed the rise called Boley Hill which John himself had used as a useful elevation from which to fire his catapults. In 1233 CE a drum tower was added to the now-repaired curtain walls. Significantly, though, the siege had shown the vulnerability of even the strongest castles and that attack was, indeed, the best form of defence.

Later History

King John's siege was not the end of Rochester's problems as the very next year Prince Louis of France (aka Louis VIII, r. 1223-1226 CE) briefly captured the castle as he launched his claim for the English throne. During more peaceful times, the Queen of Scotland, Marie de Coucy (c. 1218-1285 CE), visited the castle in 1248 CE. Rochester was again besieged, this time only for two weeks, as royalists in support of Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272 CE) took it over in April 1264 CE and they braced themselves to resist the attacking rebel forces led by Earl Simon de Montfort. The siege began on 17 April, once again the curtain wall was breached but the tower keep stood firm until the arrival of an army led by the king persuaded the attackers to withdraw on 26 April. This time, the castle was not repaired for over a century, masonry was even removed and used in other buildings, and the whole complex fell into a state of serious disrepair.

Rochester's saviour was King Edward III (r. 1327-1377 CE). A survey was carried out on the castle in 1340 CE and again in 1363 CE, both of which studies showed the massive funds needed to bring the castle back to its former glory. Work began in 1367 CE and continued, at a cost of 2262 pounds (equivalent to several million dollars today), until 1370 CE. Work carried on, too, over the next decade as every part of the castle was overhauled. Another major addition was made in the 1380s CE, the tower at the north end of the castle, now in ruins.

After the 14th century CE, the castle was not involved in any military events and James I (r. 1603-1625 CE) granted it to the statesman Sir Anthony Weldon (1583–1648 CE) whose descendants kept possession until the end of the 19th century CE. Various schemes regarding the castle came to no end, including a plan to demolish the whole thing or turn it into an army barracks. In 1965 CE the Corporation of Rochester handed over the lease to the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works, and since 1984 CE the castle has been managed by English Heritage.

![Rochester Cathedral.] Ward and Lock's Illustrated Historical Handbook to Rochester Cathedral. with Notices of Chatham and Its Dockyard and of Rochester and Its Castle, Etc.](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41LzBe4Gv3L._SL160_.jpg)