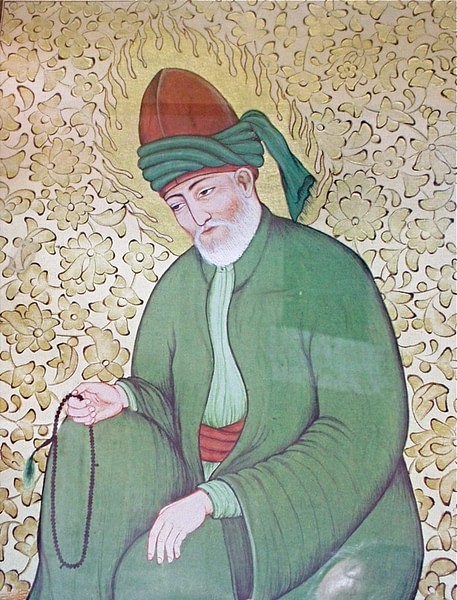

Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi (also given as Jalal ad-did Muhammad Balkhi, best known as Rumi, l. 1207-1273 CE) was a Persian Islamic theologian and scholar but became famous as a mystical poet whose work focuses on the opportunity for a meaningful and elevated life through personal knowledge and love of God.

He was a devout Sunni Muslim and, even though his poetry emphasizes a transcendence above religious strictures and dogma, it is grounded in an Islamic worldview. Rumi's God is welcoming to all, however, no matter their professed faith, and one's desire to know and praise this God is all that is required for living a spiritual life.

He was born in Afghanistan or Tajikstan to well-educated, Persian-speaking parents and followed in his father's profession as a Muslim cleric, establishing himself as a well-respected scholar and theologian until he met the Sufi mystic Shams-i-Tabrizi (l. 1185-1248 CE) in 1244 CE and embraced the mystical aspects of Islam. After Shams disappeared in 1248 CE, Rumi searched for him until he realized that Shams' spirit was with him always, even if the man himself was not present, and began composing verse which he claimed to receive from this mystical union.

Rumi's poetry is characterized by a deep understanding of the human condition which recognizes the grief of loss as well as the ecstatic joy of love. The power of transcendent love, whether for another person or God, is central to his work and conveyed through images, symbols, and stories drawn from the Quran, the hadiths, Persian mythology, legend and lore, as well as specific tableaus of daily life.

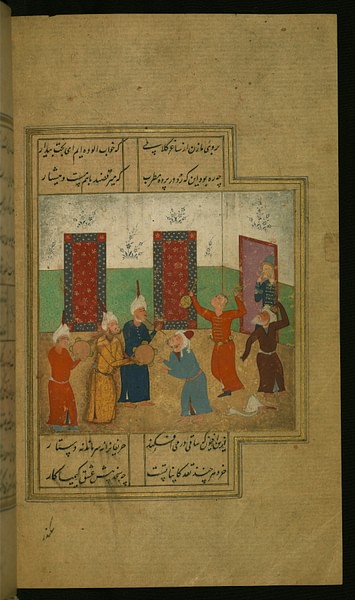

He composed his verse by spinning in circles, receiving the images he put into words, and dictating these to a scribe, thereby developing the Sufi practice of the whirling dervish as a means of apprehending the Divine. He is considered one of the greatest Persian poets of the medieval era as well as one of the most influential in world literature and his works continue to be bestsellers in the present day.

Early Life & Name

Rumi was born in the city of Balkh in modern-day Afghanistan. It has been suggested that his birthplace was Vakhsu (also given as Wakhsh) in Tajikstan but Balkh is more probable as it is known that a large Persian-speaking community flourished there in the early 13th century CE and, more significantly, one version of his name signifies his place of origin – Balkhi – “from Balkh”.

Almost nothing is known of his mother, but his father, Bahauddin Walad, was a Muslim theologian and jurist with an interest in Sufism. Sufism is the mystical approach to Islam, which rejects dogmatic strictures in favor of a personal, intimate relationship with God. Sufism is not a sect of Islam, but a transcendent path of personal spiritual revelation based on Islamic understanding. Although many orthodox Muslims of the time (and still today) rejected Sufism as a heresy, the city of Balkh encouraged its development and supported Sufi masters. How deeply Rumi's father immersed himself in Sufism in unknown, but Rumi was instructed in the mystic aspects of Sufism by one of his father's former students, Burhanuddin Mahaqqiq, which lay the foundation for his later acceptance of this spiritual path.

His name, Rumi, comes from this period as Anatolia was still referred to as the province of the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire, 330-1453 CE) it had been until 1176 CE when most of it was lost to the Muslim Turks. Someone who came from Anatolia, therefore, was referenced as a rumi, meaning a Roman.

Shams-i-Tabrizi

Shams-i-Tabrizi was a Sufi mystic who worked as a basket weaver, traveling from town to town, engaging with others but – according to legend – finding no one he could fully connect with as a friend and equal. He began to focus his travels on finding someone who, as he said, “could endure my company” and, one day, a disembodied voice answered his prayers asking, “What will you give in return?” to which Shams answered, “My head!” and the voice then replied, “The one you seek is Jelaluddin of Konya” (Banks, xix). Shams then traveled to Konya where he met Rumi.

There are a number of different accounts of this meeting but the one most often repeated is the story of the meeting in the street and Shams' question to Rumi. In this version, Rumi was riding his donkey through the marketplace when Shams seized the bridle and asked who was greater, the Prophet Muhammad or the mystic Bayazid Bestami. Rumi instantly answered that Muhammad was greater. Shams responded, "If so, why is it that Muhammad said to God 'I did not know you as I should' while Bestami said, 'Glory be to Me' in asserting that he knew God so completely that God lived and shone from within him." Rumi replied that Muhammad was still greater because he was always longing for a deeper relationship with God and acknowledged that, no matter how long he lived, he would never know God completely while Bestami embraced his mystical experience with the Divine as a final truth and went no further. After saying this, Rumi lost consciousness, falling from his donkey. Shams realized this was the man he was supposed to find and, when Rumi awoke, the two embraced and became inseparable friends (Banks, xix-xx; Lewis, 155).

Their relationship was so close that it strained Rumi's established rapport with his students, family, and associates and so, after some time, Shams left Konya for Damascus (or, according to other reports, Khoy in Azerbaijan). Rumi had him return, however, and the two resumed their former relationship which took the form of mentor-mentee on one level, with Shams as the teacher, but primarily as intellectual equals and friends.

They were conversing one evening when Shams was called to the back door. He went out to answer, did not return, and was never seen again. According to one tradition, he was murdered by one of Rumi's sons who had grown tired of the mystic monopolizing his father's time and distancing Rumi from his students. According to another, Shams chose that moment to depart from Rumi's life, possibly for the same reasons.

Either way, Rumi needed his friend back and went to find him. Scholar Coleman Banks elaborates:

The mystery of the Friend's absence covered Rumi's world. He himself went out searching for Shams and journeyed again to Damascus. It was there he realized,

Why should I seek? I am the same as

he. His essence speaks through me.

I have been looking for myself!

The union was complete. (xx)

Rumi understood there was no such thing as loss of a loved one because that person continues to live and speak and act through one's self. The depth of a close personal relationship cannot be diminished by the absence of the beloved because the beloved has become a part of the self. Rumi the theologian became Rumi the mystic poet at this realization and began composing verse which he believed came from Shams.

Rumi the Poet

Rumi's grief at the loss of his friend found expression in the poetic form of the ghazal which laments loss at the same time as it celebrates the experience being mourned. One would not be feeling such depth of loss, so a ghazal would say, if the experience had not been so beautiful; one should, therefore, be grateful for that experience even as one mourns. Rumi's early poetry was published as the Divan of Shams Tabrizi (a divan meaning a collection of an artist's short works) which Rumi believed to have been composed by Shams' spirit dwelling with his own.

These poems are not monumental in the Western sense of memorializing moments; they are not discrete entities but a fluid, continuously self-revising, self-interrupting medium. They are not so much about anything as spoken from within something. Call it enlightenment, ecstatic love, spirit, soul, truth, the ocean of ilm (divine luminous wisdom), or the covenant of alast (the original agreement with God). Names do not matter. Some resonance of ocean resides in everyone. Rumi's poetry can be felt as a salt breeze from that, traveling inland. (xxiii-xxiv)

Rumi drew on the entirety of his life – the lived experiences in the physical world as well as the numinous glimpses of eternity – to compose his verse but the underlying and resonating power of all of his poems was love. To Rumi, love was the great elevator from the mundane to the sublime, from the horizontal experience of everyday life to the vertical ascent to God in all of one's daily activities, no matter how simple. His efforts have been recognized in the creation of poetry which continues to resonate around the world.

Rumi's Works

Rumi's best-known works are the Masnavi, the Divan of Shams Tabrizi, and the prose works of the Discourses, Letters, and Seven Sermons. The Masnavi's title refers to the form of the work. A masnavi (known as mathnawi in Arabic) is a Persian form of poetry comprised of rhyming couplets of indefinite length. Rumi's Masnavi is a six-volume poetic work, considered not only his masterpiece but a masterpiece of world literature, exploring people's relationship to God as well as to themselves, each other, and the natural world. Scholar Jawid Mojaddedi writes:

Rumi's Masnavi holds an exalted status in the rich canon of Persian Sufi literature as the greatest mystical poem ever written. It is even referred to commonly as “the Koran in Persian”. (xx)

Although there is no doubt that Rumi drew on Shams' spirit for inspiration, he was well-educated in Arabic and Persian literature and folklore and especially inspired by earlier Persian poets such as Sanai (l. 1080 - c. 1131 CE) and Attar of Nishabur. Sanai, who resigned his position as court poet to pursue the Sufi path, wrote the masterpiece The Walled Garden of Truth in which he explores the concept of the unity of existence, claiming that “error begins with duality”. As soon as one distances one's self from others – or God – one establishes an “us vs. them” dichotomy which leaves one isolated and frustrated. One must embrace the totality of existence, recognizing no distance between one's self, others, and God, in order to understand the nature of existence and forge a personal relationship with the Divine. Artificial divisions of religious dogma only serve to isolate while acceptance of others' religious beliefs and practices enlarges one's own experience of God in whom there are no divisions, only acceptance and unconditional love.

Another well-known story in the Masnavi is the brief and simple tale in Book One about the lover who knocks on the door of his beloved's house (vv. 3069-76). When she asks, “Who's there?” he answers, “It is I!” and is consequently turned away. Only after being 'cooked by separation's flame' (v. 3071) does he learn from his mistake and perceive the reality of the situation. He returns to knock on her door, and this time, on being asked “Who's there?” he answers, “It is you”, and is admitted to where two I's cannot be accommodated. (xxv)

The lover and the beloved are one, whether on the earthly plane or the higher reaches of the Divine, and artificial definitions, shallow understandings, and prejudices only serve to separate one from true understanding of one's place in the universe and prohibit one from the possibility of honest communion with God. The more one insists on a “right way” to praise, serve, and worship God, the further one separates one's self, as illustrated in the poem Moses and the Shepherd.

In this poem, Moses (known as Musa in Islamic tradition) overhears a poor shepherd who is praising God saying how he would comb God's hair, wash his clothes, care for his shoes, serve him milk, and clean his house, he loves Him so much. Moses sharply rebukes the shepherd, telling him that God is infinite and has no need for any human to do any of these things and the man should refrain from speaking such nonsense. The shepherd accepts the rebuke and wanders away into the desert. God then chastises Moses, saying:

You have separated me from one of my own. Did you come as a Prophet to unite or to sever?

I have given each being a separate and unique way of seeing and knowing and saying that knowledge.

What seems wrong to you is right for him.

What is poison to one is honey to someone else.

I am apart from all that.

Ways of worshipping are not to be ranked as better or worse than one another. (Banks, 166)

Moses repents, tracks down the shepherd, and apologizes. The shepherd forgives him, telling him that he has already come to the realization that the nature of God is nothing like he imagined. Rumi, as narrator, comments, “Whenever you speak praise or thanksgiving to God, it is always like this dear shepherd's simplicity” (Banks, 168). This poem exemplifies Rumi's practice of using stories from the Quran, or other Islamic literature, to make a point his audience would already be apt to accept.

In the Quran, Surah 18:60-82, Moses is depicted in similar fashion when God sends him to follow Al-Khidr (God's representative). Al-Khidr tells Moses outright that, if he would follow him, he must not question any of his actions. Moses agrees but then questions Al-Khidr repeatedly. At the end of the story, Al-Khidr explains himself and it is apparent that Moses had no patience in accepting God's plan without knowing what that plan might entail and the end result. The use of a famous religious figure as a character who still needs to be taught, and is open to learning from God, would encourage humility in an audience who were nowhere near Moses' spiritual stature.

The greatest lesson one could learn, according to Rumi, could not be “taught” but had to be experienced, and that was the elevation of the soul through love. When one falls in love with another person, one does not limit that response by ticking off a list of what one should or should not do to please the other; one simply falls in love and allows the relationship to then dictate one's behavior.

In this same way, Rumi says, one should fall in love with the Divine and only then will one realize what is important in life and what can safely be let go of. Although Rumi was a devout Muslim, he refused to allow the dogma of his religion interfere with his relationship with God or other people. His poetry remains relevant in the present day for this very reason: the transcendence of Divine love does not recognize artificial human constructs and is open and welcoming to all people, no matter what they may believe or whether they believe at all.

Conclusion

Rumi expresses this concept in a number of poems but clearly in his Love Dogs in which a man continually cries out to God until he is silenced by a cynic who asks him why he continues to pray when he gets no answer. The man stops praying and falls into a fitful sleep in which Al-Khidr comes and asks him why he stopped his prayers. The man answers, “Because I've never heard anything back” and Al-Khidr answers, “This longing you express is the return message.” Rumi then speaks directly to the reader saying, “Listen to the moan of a dog for its master. /That whining is the connection” (Banks, 155-156). The human experience of longing for a relationship with the Divine, according to Rumi, is the answer to one's prayers. One should then embrace that longing as love, replacing doubt and confusion with faith and the comfort of the beloved one has longed for.

Rumi continued to compose his Masnavi (which was never completed) until his death in 1273 CE. By this time, he was known as Mawlawi (also given as Mevlana, “our master”) for his spiritual wisdom, insight, and skill in composing verse. His death was mourned by the diverse community of Konya –Muslims, Jews, and Christians united in grief at his passing – and the entourage followed the poet's remains to where they were interred in the sultan's rose garden beside Rumi's father's. The Sufi community Rumi had developed, the Mevlevi Order, built a grand mausoleum over his grave in 1274 CE which, today, is part of the Mevlana Museum of Konya, Turkey, a site visited by admirers from all over the world who still come to pay their respects to the master.