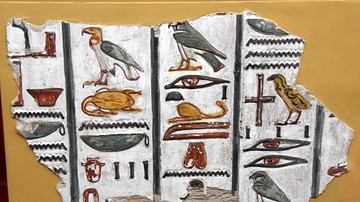

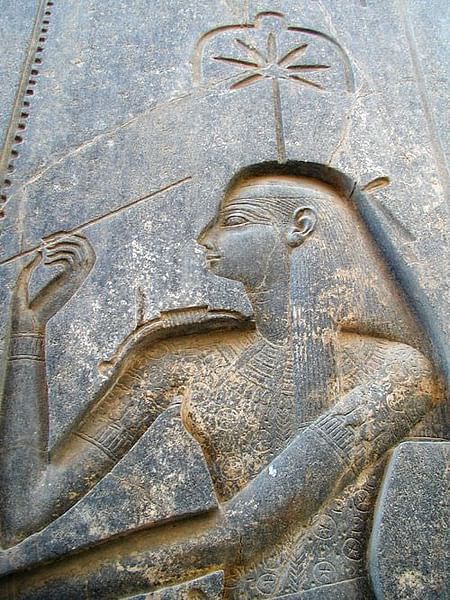

Seshat (also given as Sefkhet-Abwy and Seshet) is the Egyptian goddess of the written word. Her name literally means "female scribe" and she is regularly depicted as a woman wearing a leopard skin draped over her robe with a headdress of a seven-pointed star arched by a crescent in the form of a bow.

This iconography has been interpreted as symbolizing supreme authority in that it is common in Egyptian legend and mythology for one to wear the skin of a defeated enemy to take on the foe's powers, stars were closely associated with the realm of the gods and their actions, and the number seven symbolized perfection and completeness.

The leopard skin would represent her power over, and protection from, danger as leopards were a common predator. The crescent above her headdress, resembling a bow, could represent dexterity and precision, if one interprets it along the lines of archery, or simply divinity if one takes the symbol as representing light, along the lines of later depictions of saints with halos.

Among her responsibilities were record keeping, accounting, measurements, census-taking, patroness of libraries and librarians, keeper of the House of Life (temple library, scriptorium, writer's workshop), Celestial Librarian, Mistress of builders (patroness of construction), and friend of the dead in the afterlife. She is often depicted as the consort (either wife or daughter) of Thoth, god of wisdom, writing, and various branches of knowledge.

She first appears in the 2nd Dynasty (c. 2890- c. 2670 BCE) of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) as a goddess of writing and measurements assisting the king in the ritual known as "stretching of the cord" which preceeded the construction of a building, most often a temple.

The ancient Egyptians believed that what was done on earth was mirrored in the celestial realm of the gods. The daily life of an individual was only part of an eternal journey which would continue on past death. Seshat featured prominently in the concept of the eternal life granted to scribes through their works. When an author created a story, inscription, or book on earth, an ethereal copy was transferred to Seshat who placed it in the library of the gods; mortal writings were therefore also immortal.

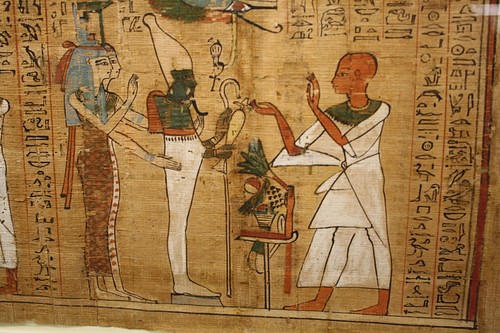

Seshat was also sometimes depicted helping Nephthys revive the deceased in the afterlife in prepration for their judgment by Osiris in the Hall of Truth. In this capacity, the goddess would have helped the new arrival recognize the spells of The Egyptian Book of the Dead, enabling the soul to move on toward the hope of paradise.

Unlike the major gods of Egypt, Seshat never had her own temples, cult, or formal worship. Owing to the great value Egyptians placed on writing, however, and her part in the construction of temples and the afterlife, she was venerated widely through commonplace acts and daily rituals from the Early Dynastic Period to the last dynasty to rule Egypt, the Ptolemaic Dynasty of 323-30 BCE. Seshat is not as well known today as many of the other deities of ancient Egypt but, in her time, she was among the most important and widely recognized of the Egyptian pantheon.

Responsibilities & Duties

According to one myth, the god Thoth was self-created at the beginning of time and, in his form as an ibis, lay the primordial egg which hatched creation. There are other versions of Thoth's birth as well but they all make mention of his vast knowledge and the great gift of writing he offered to humanity.

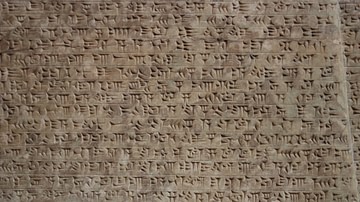

Thoth was worshipped as early as the Pre-Dynastic Period (c. 6000- c. 3150 BCE) at a time when Egyptian writing consisted of pictographs, images representing specific objects, prior to their development into hieroglyphics, symbols representing sounds and concepts. At this time, Thoth seems to have been considered a god of wisdom and knowledge - as he remained - and once a writing system was developed it was attributed to him.

Perhaps because Thoth already had so many responsibilities, the Egyptians transferred the supervision of writing to the goddess Seshat. Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson notes how Seshat appears in reliefs and inscriptions in the Early Dynastic Period as a goddess of measurements and writing, clearly indicating she was already an important deity at that time:

Representations show the king involved in a foundation ritual known as "stretching the cord" which probably took place before work began on the construction of a temple or of any addition. These depictions usually show the king performing the rite with the help of Seshat, the goddess of writing and measurement, a mythical aspect which reinforced the king's central and unique role in the temple construction. (Symbol & Magic, 174)

Seshat's responsibilities were many. As record-keeper she documented everyday events but, beginning in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2613-c. 2181 BCE), she also recorded the spoils of war in the form of animals and captives. She also kept track of tribute owed and tribute paid to the king and, beginning in the New Kingdom (c. 1570- c. 1069 BCE), was closely associated with the pharaoh recording the years of his reign and his jubilee festivals.

Egyptologist Rosalie David notes how she "wrote the king's name on the Persea tree, each leaf representing a year in his allotted lifespan" (Religion and Magic, 411). Throughout all these periods, and later, her most important role was always as the goddess of precise measurements and all forms of the written word. The Egyptians placed great value on attention to detail and this was as true, if not more so, in writing as any other aspect of their lives.

Importance of Writing in Egypt

The written word was considered a sacred art. The Greek designation hieroglyphics for the Egyptian writing system means "sacred carvings" and is a translation from the Egyptian phrase medu-netjer, "the god's words". Thoth had given the gift of writing to humanity and it was a mortal's responsibility to honor that gift by practicing the craft as precisely as possible. Rosalie David comments on the Egyptian ideal of writing:

The main purpose of writing was not decorative and it was not originally intended for literary or commercial use. Its most important function was to provide a means by which certain concepts or events could be brought into existence. The Egyptians believed that if something were comitted to writing it could be repeatedly "made to happen" by means of magic. (Handbook,199)

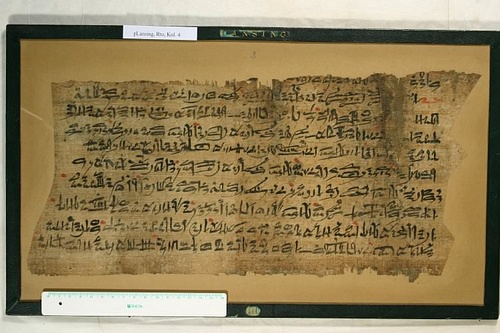

The spells of The Egyptian Book of the Dead are the best examples of this concept. The Book of the Dead is a guide through the afterlife written for the deceased. The spells the soul speaks help one to navigate through assorted dangers to arrive at the perfect paradise of the Field of Reeds. One needed to know how to avoid demons, how to transform one's self into various animals, and how to address the entities one would meet in the next world and so the spells had to be precise in order to work.

The Book of the Dead evolved from the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom but, even before this time, one can see the Egyptian precision in writing at work in the Offering Lists and Autobiographies of tombs in the latter part of the Early Dynastic Period. Writing, as David notes, could bring concepts or events into existence - from a king's decree to a mythological tale to a law, a ritual, or an answered prayer - but it also held and made permanent that which had passed out of existence.

Writing made the transitory world of change into one everlasting and eternal. The dead were not gone as long as their stories could be read in stone; nothing was ever really lost. The sacred carvings of the Egyptians were so important to them that they dedicated whole sections of temples or temple complexes to a literary institution known as The House of Life.

House of Life

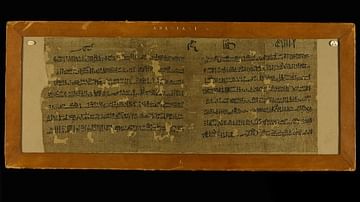

The House of Life was a combination library, scriptorium, institute of higher learning, writer's workshop, print shop/copy center, publisher, and distributor. The Egyptians referred to the institution as Per-Ankh (literally "House of Life") and it is first mentioned in inscriptions from the Middle Kingdom.

These were located in temples or temple complexes and would have been presided over by Seshat and Thoth no matter which god the temple was dedicated to. Since the gods were thought to literally reside in their temples, this arrangement would be comparable to having a permanent house-guest in one's home who takes care of responsibilities one may value but simply has not time for. Wilkinson notes how "by virtue of her role in the foundation ceremony [Seshat] was a part of every temple building" (Complete Gods, 167). She was also an integral part of the temple through her supervision of the House of Life. Historian and Egyptologist Margaret Bunson describes their function:

Research was conducted in the House of Life because medical, astronomical, and mathematical texts perhaps were maintained there and copied by scribes. The institution served as a workshop where sacred books were composed and written by the ranking scholars of the times. It is possible that many of the texts were not kept in the Per-Ankh but discussed there and debated. The members of the institution's staff, all scribes, were considered the learned men of their age. Many were ranking priests in the various temples or noted physicians and served the various kings in many administrative capacities. (204-205)

The scribes were most commonly associated with the sun god Ra in earlier times and with Osiris in later periods no matter which god resided in a particular temple. Bunson claims that probably only very important cities could support a Per-Ankh but other scholars, Rosalie David among them, cite evidence that "every sizable town had one" (Handbook, 203). Bunson's theory is substantiated by the known structures identified as a Per-Ankh at Amarna, Edfu, and Abydos, all important cities in ancient Egypt, but this does not mean there were not others elsewhere; only that these have not been positively identified as yet.

Seshat's role at the House of Life would have been the same as anywhere else: she would have received a copy of the texts written there for the library of the gods where it would be kept eternally. Rosalie David writes:

It would seem that the House of Life had both a practical use and a deeply religious significance. Its very title may reflect the power of life that was believed to exist in the divinely inspired writings composed, copied, and often stored there...In one ancient text the books in the House of Life are claimed not only to have the ability to renew life but actually to be able to provide the food and sustenance needed for the continuation of life. (Handbook, 203-204)

It is a certainty that the majority of the priests and scribes of the Per-Ankh were men but some scholars have pointed to evidence for female scribes. Since Seshat was herself a divine female scribe it would make sense that women practiced the art of writing as well as men.

Female Scribes

Women in ancient Egypt enjoyed a level of equality unmatched in the ancient world. It is well substantiated that women could be, and were, scribes in that we have names of female physicians and images of women in important religious posts such as God's Wife of Amun; both of these occupations required literacy. Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley writes:

Although the only Egyptian woman to be depicted actually putting pen to paper was Seshat, the goddess of writing, several ladies were illustrated in close association with the traditional scribe's writing kit of palette and brushes. It is certainly beyond doubt that at least some of the daughters of the king were educated and the position of private tutor to a royal princess could be one of the highest honour. (118-119)

It is known, for example, that the female pharaoh Hatshepsut (r. 1479-1458 BCE) hired a tutor for her daughter Neferu-Ra and that Queen Nefertiti (r. c. 1370- c. 1336 BCE) was literate as was her mother-in-law, Queen Tiye (r. 1398-1338 BCE). Still, when it comes to the majority of women in Egypt, images and inscriptions leave some doubt as to how many could actually read and write. Egyptologist Gay Robins explains:

In a few New Kingdom scenes, women are depicted with scribal kits under their chairs and it has been suggested that the women were commemorating their ability to read and write. Unfortunately, in all cases but one, the woman is sitting with her husband or son in such a way that it would cramp the available space to put the kit under the man's chair, and so it may have been moved back to a place under the woman's. This happens in a similar scene when the man's dog is put under the woman's chair. So one cannot be sure that the scribal kit belonged to the woman. If there was a large group of literate women in ancient Egypt, they do not seem to have developed any surviving literary genres unique to themselves. (113)

While this may be true, one cannot discount the possibility that female scribes were responsible for works of literature, either in creating or copying them. Egyptian society was quite conservative and written works generally adhered to a set structure and theme throughout the various periods of history. Even in the New Kingdom, where literature was more cosmopolitan, it still adhered to a basic form which elevated Egyptian cultural values. Arguing that there were few female scribes based on there being no "women's literature" in ancient Egypt seems in error as the literature of the culture could hardly be considered "masculine" in any respect save for the kings' monumental inscriptions.

In the famous story of Osiris and his murder by Set it is not Osiris who is the hero of the tale but his sister-wife Isis. Although the best-known creation myth features the god Atum standing on the ben-ben at the beginning of time, an equally popular one in Egypt has the goddess Neith creating the world. Bastet, goddess of the hearth, home, women's health and secrets, was popular among both men and women and the goddess Hathor was regularly invoked by both at festivals, parties, and family gatherings.

The deity who presided over the brewing of beer, the most popular drink in Egypt, was not male but the goddess Tenenet and the primary protector and defender of Isis when she was a single mother safe-guarding Horus was the goddess Serket. Seshat is only one of a number of female deities venerated in ancient Egypt reflecting the high degree of respect given to women and their abilities in a number of different areas of daily life.

Seshat the Foundation

As noted, although Seshat never had a temple of her own, she was the foundation of the temples constructed in her role as Mistress of Builders and her participation in the ritual ceremony of "stretching the cord" which measured the dimensions of the structure to be raised. The floor plan of the temple was laid out through the "stretching the cord" ceremony after an appropriate area of land had been decided upon. Wilkinson comments on the process of situating a temple and Seshat's ritual role in this:

The rite involved the careful orientation of the temple by astronomical observation and measurement. Apparently this was usually accomplished by sighting the stars of a northern circumpolar constellation through a notched wooden instrument called a merkhet and thus acquiring a true north-south orientation which was commonly used for the temple's short axis. According to the texts, the king was assisted in this ritual by Seshat (or Sefkhet-Abwy), the scribal goddess of writing and measurement. (Temples, 38)

In addition to setting the foundation of the temple, Seshat also was responsible for the written works that temple produced and housed in its House of Life and, further, for gathering these works into her eternal library in the realm of the gods. Although Thoth was responsible for the initial gift of writing, his consort Seshat lovingly gathered the works that gift produced, presided over them in the libraries on earth, and kept them eternally safe on her shelves in the heavens.

As writing was both a creative and preserving art, one which brought concepts to life and caused them to endure, which bestowed eternal life on both the writer and the subject, Seshat would be considered by the ancient Egyptians as the goddess responsible for the preservation of Egyptian culture and its enduring fascination among the people of the present day.