Shinto means 'way of the gods' and it is the oldest religion in Japan. Shinto's key concepts include purity, harmony, family respect, and subordination of the individual before the group. The faith has no founder or prophets and there is no major text which outlines its principal beliefs.

The flexibility in the definition of what Shinto is exactly may be one of the reasons for its longevity. Shinto has become so interwoven with Japanese culture in general that it is almost inseparable as an independent body of thinking. Consequently, Shinto has become part of the Japanese character whether the individual claims a religious affiliation or not.

Origins of Shinto

Unlike many other religions, Shinto has no recognised founder. The peoples of ancient Japan had long held animistic beliefs, worshipped divine ancestors and communicated with the spirit world via shamans; some elements of these beliefs were incorporated into the first recognised religion practised in Japan, Shinto, which began during the period of the Yayoi culture (c. 300 BCE - 300 CE). For example, certain natural phenomena and geographical features were given an attribution of divinity. Most obvious amongst these are the sun goddess Amaterasu and the wind god Susanoo. Rivers and mountains were especially important, none more so than Mt. Fuji, whose name derives from the Ainu name 'Fuchi,' the god of the volcano.

In Shinto gods, spirits, supernatural forces and essences are known as kami, and governing nature in all its forms, they are thought to inhabit places of particular natural beauty. In contrast, evil spirits or demons (oni) are mostly invisible with some envisioned as giants with horns and three eyes. Their power is usually only temporary, and they do not represent an inherent evil force. Ghosts are known as obake and require certain rituals to send away before they cause harm. Some spirits of dead animals can even possess humans, the worst being the fox, and these individuals must be exorcised by a priest.

Kojiki & Nihon Shoki

Two chronicles, commissioned by the imperial house (Emperor Temmu), are invaluable sources on Shinto mythology and beliefs. The Kojiki ('Record of Ancient Things') was compiled in 712 CE by the court scholar Ono Yasumaro, who drew on earlier sources, mostly genealogies of powerful clans. Then the Nihon Shoki ('Chronicle of Japan' and also known as the Nihongi), written by a committee of court scholars, came in 720 CE which sought to redress the bias many clans thought the earlier work had given to the Yamato clan. These works, then, describe the 'Age of the Gods' when the world was created and they ruled before withdrawing to leave humanity to rule itself. They also gave the imperial line a direct descent from the gods - the original purpose of their composition - with the goddess Amaterasu's great-great-grandson Jimmu Tenno being the first emperor of Japan. Jimmu's traditional rule dates are 660-585 BCE, but he may well be a purely mythical figure. The Nihon Shoki, gives us our first textual instance of the word 'Shinto.'

Other important sources on early Shinto beliefs include the Manyoshu or 'Collection of 10,000 Leaves.' Written c. 760 CE, it is an anthology of poems covering all manner of topics not limited to religion. Another source is the many local chronicles, or Fudoki, which were commissioned in 713 CE to record local kami and associated legends in the various provinces. Finally, there is the Engishiki, a collection of 50 books compiled in the 10th century CE, covering the laws, rituals and prayers of Shinto.

Shinto Gods

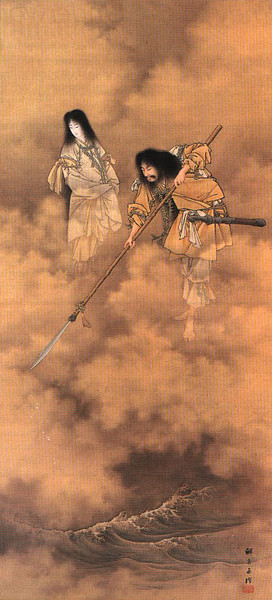

As with many other ancient religions, the Shinto gods represent important astrological, geographical, and meteorological phenomena which are ever present and considered to affect daily life. These gods or ujigami, were associated with specific ancient clans or uji. Unusually, the sun and supreme deity is female, Amaterasu. Her brother is Susanoo, the god of the sea and storms. The creator gods are Izanami and Izanagi, who formed the islands of Japan. From Izanagi's left eye was born Amaterasu while from his nose sprang Susanoo. From the god's right eye Tsukuyomi, the moon god was born.

Susanoo and Amaterasu battled with each other following Susanoo's disgraceful behaviour. Amaterasu hid herself in a cave, darkening the world, and the gods could not tempt her out again despite offering fine jewels and a mirror. Finally, an erotic dancer caused such laughter that Amaterasu relented and came out to see the fuss. Susanoo turned over a new leaf, and, slaying an eight-headed dragon monster which was terrifying a farming family, he gave the sword he found in one of the creature's eight tails to Amaterasu in reconciliation. The dispute is taken by historians to represent the victory of the Yamato clan (represented by Amaterasu) over their rivals the Izumo (represented by Susanoo).

Susanoo returned to earth, the 'Reed Plain,' and married a daughter of the family he had saved from the monster Yamato no Orochi. Together they created a new race of gods who ruled the earth. Eventually, Amaterasu became concerned at the power these gods wielded, and so she sent her grandson Honinigi with certain symbols of sovereignty. These were the jewels and mirror the gods used to persuade Amaterasu out of her cave and the sword given to her by Susanoo, known later as Kusanagi. These three objects would become part of the imperial regalia of Japan. Another symbol carried by Honinigi was the magnificent magatama jewel which had special fertility powers.

Honinigi landed on Mt. Takachio in Kyushu and made a deal with the most powerful of the gods, Okuninushi. For his loyalty to Amaterasu, Okuninushi would have the important role of protector of the future royal family. Later, the god would be regarded as the protector of all Japan.

Other important divine figures include Inari the rice god kami, seen as particularly charitable and important also to merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans. Inari's messenger is the fox, a popular figure in temple art. The 'Seven Lucky Gods' or Shichifukujin are understandably popular, especially Daikokuten and Ebisu who represent wealth. Daikokuten is also considered the god of the kitchen and so is revered by cooks and chefs.

As described below, the Shinto and Buddhist faiths became closely intertwined in ancient Japan, and as a consequence, some Buddhist figures, the bosatsu or 'enlightened beings,' became popular kami with practitioners of Shinto. Three such figures are Amida (ruler of the Pure Land, i.e. heaven), Kannon (protector of children, women in childbirth, and dead souls) and Jizo (protector of those in pain and the souls of dead children). Another popular figure who crosses both faiths is Hachiman, a warrior god.

Finally, some mortals were given divine status after their deaths. Perhaps the most famous example is the scholar Sugawara no Michizane, aka Tenjin (845-903 CE), who was badly treated at court and exiled. A wave of devastating fires and plague shortly after his death hit the imperial capital which many took as a sign from the gods of their anger at Tenjin's unjust treatment. The impressive Kitano Tenmangu shrine at Kyoto was built in 947 CE in his honour, and Tenjin became the patron god of scholarship and education.

Shinto & Buddhism

Buddhism had arrived in Japan in the 6th century BCE as part of the Sinification process of Japanese culture. Other elements not to be ignored here are the principles of Taoism and Confucianism which travelled across the waters just as Buddhist ideas did, especially the Confucian importance given to purity and harmony. These different belief systems were not necessarily in opposition, and both Buddhism and Shinto found enough mutual space to flourish side by side for many centuries in ancient Japan.

By the end of the Heian period (794-1185 CE), some Shinto kami spirits and Buddhist bodhisattvas were formally combined to create a single deity, thus creating Ryobu Shinto or 'Double Shinto.' As a result, sometimes images of Buddhist figures were incorporated into Shinto shrines and some Shinto shrines were managed by Buddhist monks. Of the two religions, Shinto was more concerned with life and birth, showed a more open attitude to women, and was much closer to the imperial house. The two religions would not be officially separated until the 19th century CE.

What are the Key Concepts in Shinto?

The main beliefs or key concepts of Shinto are:

- Purity - both physical cleanliness and the avoidance of disruption, and spiritual purity.

- Physical well-being.

- Harmony (wa) exists in all things and must be maintained against imbalance.

- Procreation and fertility.

- Family and ancestral solidarity.

- Subordination of the individual to the group.

- Reverence of nature.

- All things have the potential for both good and bad.

- The soul (tama) of the dead can influence the living before it joins with the collective kami of its ancestors.

Shinto Shrines

Shinto shrines, or jinja, are the sacred locations of one or more kami, and there are some 80,000 in Japan. Certain natural features and mountains may also be considered shrines. Early shrines were merely rock altars on which offerings were presented. Then, buildings were constructed around such altars, often copying the architecture of thatched rice storehouses. From the Nara period in the 8th century CE temple design was influenced by Chinese architecture - upturned gables, and a prodigious use of red paint and decorative elements. Most shrines are built using Hinoki Cypress.

Shrines are easily identified by the presence of a torii or sacred gateway. The simplest are merely two upright posts with two longer crossbars and they symbolically separate the sacred space of the shrine from the external world. These gates are often festooned with gohei, twin paper or metal strips each ripped in four places and symbolising the kami's presence. A shrine is managed by a head priest (guji) and priests (kannushi), or, in the case of smaller shrines, by a member of the shrine elders committee, the sodai. The local community supports the shrine financially. Finally, private households may have an ancestor shrine or kamidana which contains the names of the family members who have passed away and honours the ancestral kami.

The typical Shinto shrine complex includes the following common features:

- The torii or sacred entrance gate.

- The honden or sanctuary which contains an image of the shrine's kami.

- The goshintai or sacred object inside the honden which is invested with the spirit of the kami.

- The sando or sacred path joining the torii and haiden.

- The haiden or oratory hall for ceremonies and worship.

- The heiden, a building for prayers and offerings.

- The saisenbako, a box for money offerings.

- The temizuya, a stone water trough for ritual cleansing.

- The kaguraden, a pavilion for ritual dancing and music.

- Larger shrines also have a large assembly hall and stalls where charms are sold by miko ('shrine virgins').

The most important Shinto shrine is the Ise Grand Shrine dedicated to Amaterasu with a secondary shrine to the harvest goddess Toyouke. Beginning in the 8th century CE, a tradition arose of rebuilding exactly the shrine of Amaterasu at Ise every 20 years to preserve its vitality. The broken-down material of the old temple is carefully stored and transported to other shrines where it is incorporated into their walls.

The second most important shrine is that of Okuninushi at Izumo-taisha. These two are the oldest Shinto shrines in Japan. Besides the most famous shrines, every local community had and still has small shrines dedicated to their particular kami spirits. Even modern city buildings can have a small Shinto shrine on their roof. Some shrines are even portable. Known as mikoshi, they can be moved so that ceremonies can be held at places of great natural beauty such as waterfalls.

Worship & Festivals

The sanctity of shrines means that worshippers must cleanse themselves (oharai) before entering them, commonly by washing their hands and mouth with water. Then, when ready to enter, they make a small money offering, ring a small bell or clap their hands twice to alert the kami and then bow while saying their prayer. A final clap indicates the end of the prayer. It is also possible to request a priest offer one's prayer. Small offerings might include a bowl of sake (rice wine), rice, and vegetables. As many shrines are in places of natural beauty such as mountains, visiting these shrines is seen as an act of pilgrimage, Mt. Fuji being the most famous example. Believers sometimes wear Omamori, too, which are small embroidered sachets containing prayers to guarantee the person's well-being. As Shinto has no particular view on the afterlife, Shinto cemeteries are rare. Most followers are cremated and interred in Buddhist cemeteries.

The calendar is punctuated by religious festivals to honour particular kami. During these events, portable shrines may be taken to sites linked to a kami, or there are parades of colourful floats, and worshippers sometimes dress to impersonate certain divine figures. Amongst the most important annual festivals are the three-day Shogatsu Matsuri or Japanese New Year festival, the Obon Buddhist celebration of the dead returning to the ancestral home which includes many Shinto rituals, and the annual local matsuri when a shrine is transported around the local community to purify it and ensure its future well-being.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.