The 1588 Spanish Armada was a fleet of 132 ships assembled by King Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598) to invade England, his 'Enterprise of England'. The Royal Navy of Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) met the Armada in the English Channel and, thanks to superior manoeuvrability, better firepower, and bad weather, the Spanish were defeated.

After the battle, the remains of the Armada were then obliged to sail around the dangerous shores of Scotland and so more ships and men were lost until only half of the fleet eventually made it back to Spanish waters. The English-Spanish war continued, and Philip tried to invade with future naval expeditions, but the defeat of the 1588 Armada became the stuff of legend, celebrated in art and literature and regarded as a mark of divine favour for the supremacy of Protestant England over Catholic Spain.

Prologue: Three Queens & One King

Philip of Spain's interest in England went back to 1553 when his father, King Charles V of Spain (r. 1516-1556) arranged for him to marry Mary I of England (r. 1553-1558). Mary was a staunch Catholic but her reversal of the English Reformation and proposed marriage to a prince of England's great rival and then the richest country in Europe led to open revolt - the Wyatt Rebellion of January 1554. Mary quashed the revolt, persecuted Protestants to earn her nickname 'Bloody Mary', and married Philip anyway. As it turned out, the marriage was not a happy one, and Philip spent most of his time as far as possible from his wife. Philip became the King of Spain in 1556 and so Mary its queen but she died in 1558 of cancer. Philip wasted no time whatsoever and proposed to Mary's successor, her sister Elizabeth. The Virgin Queen rejected the offer, along with many others, and she steered her kingdom away from Catholicism.

Elizabeth reinstated the Act of Supremacy (April 1559), which put the English monarch at the head of the Church (as opposed to the Pope). As a result, the Pope excommunicated the queen for heresy in February 1570. Elizabeth was also active abroad. She attempted to impose Protestantism in Catholic Ireland but this only resulted in frequent rebellions (1569-73, 1579-83, and 1595-8) which were often materially supported by Spain. The queen also sent money and arms to the Huguenots in France and financial aid to Protestants in the Netherlands who were protesting against Philip's rule.

The queen's religious and foreign policies put Elizabeth directly against Philip who saw himself as the champion of Catholicism in Europe. Then a third monarch arrived on the stage, Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542-1567). Catholic Mary was the granddaughter of Mary Tudor, sister of Henry VIII, and she had been unpopular in Protestant Scotland and forced to abdicate in 1567 and then flee the country in 1568. Kept in confinement by her cousin Elizabeth, Mary became a potential figurehead for any Catholic-inspired plot to remove Elizabeth from her throne. Indeed, for many Catholics, Elizabeth was illegitimate as they did not recognise her father's divorce from his first wife Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536). Several plots did occur, notably a failed rebellion in the north of England stirred up by the earls of Northumberland and Westmorland, both staunch Catholics. Then the conspiratorial Duke of Norfolk, who had plotted with Spain to mount an invasion of England and crown Mary queen (the 1571 Ridolfi plot), was executed in 1572. These were dangerous times for Elizabeth as seemingly everyone wanted her throne, none more so than Philip of Spain.

English-Spanish Relations

When Mary, Queen of Scots was executed on 8 February 1587, Philip had one more reason to attack England. Philip was angry at rebellions in the Netherlands which disrupted trade and Elizabeth's sending of several thousand troops and money to support the Protestants there in 1585. If the Netherlands fell, then England would surely be next. Other bones of contention were England's rejection of Catholicism and the Pope, and the action of privateers, 'sea dogs' like Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596) who plundered Spanish ships laden with gold and silver taken from the New World. Elizabeth even funded some of these dubious exploits herself. Spain had not been entirely innocent either, confiscating English ships in Spanish ports and refusing to allow English merchants access to New World trade. When Drake attacked Cadiz in 1587 and 'singed the king's beard' by destroying valuable ships and supplies destined for Spain, Philip's long-planned invasion, what he called the 'Enterprise of England', was delayed, but the Spanish king was determined. Philip even gained the blessing and financial aid of Pope Sixtus V (r. 1585-90) as the king presented himself as the Sword of the Catholic Church.

The Fleets

Philip finally assembled his massive fleet, an 'armada' of 132 ships, although his financial problems and the English attacks on supplies from the New World did not allow him to build a navy quite as large as he had hoped. The Armada, packed already with 17,000 soldiers and 7,000 mariners, sailed from Lisbon (then under Philip's rule) on 30 May 1588. It was intended that the Armada would establish dominance of the English Channel and then reach the Netherlands in order to pick up a second army led by the Duke of Parma, Philip's regent there. Parma's multinational army consisted of Philip's best troops and included Spaniards, Italians, Germans, Burgundians, and 1,000 disaffected Englishmen. The fleet would then sail to invade England. Philip's force was impressive enough but the king hoped that once in England, it would be swelled by English Catholics eager to see Elizabeth's downfall. The Armada was commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, and Philip had promised Medina on his departure, "If you fail, you fail; but the cause being the cause of God, you will not fail" (Phillips, 123).

Henry VIII of England (r 1509-1547) and Mary I had both invested in England's Royal Navy and Elizabeth would reap the rewards of that foresight. England's fleet of around 130 ships was commanded by Lord Howard of Effingham. The large Spanish galleons - designed for transportation, not warfare - were much less nimble than the smaller English ships which would, it was hoped, be able to dash in and out of the Spanish fleet and cause havoc. In addition, the 20 English royal galleons were better armed than the best of the Spanish ships and their guns could fire further. The English also benefitted from such experienced and audacious commanders as vice-admiral Drake whom the Spanish called 'El Draque' ('the Dragon') and who had circumnavigated the globe in the Golden Hind (1577-80). Another notable commander with vast sailing experience was Martin Frobisher (c. 1535-1594) in the Triumph, while old sea salts like John Hawkins (1532-1595) had ensured, as treasurer since 1578, the navy had the best equipment Elizabeth could afford, including such fine ships as Drake's flagship, the Revenge, and Howard's flagship, the ultra-modern Ark Royal.

Battle

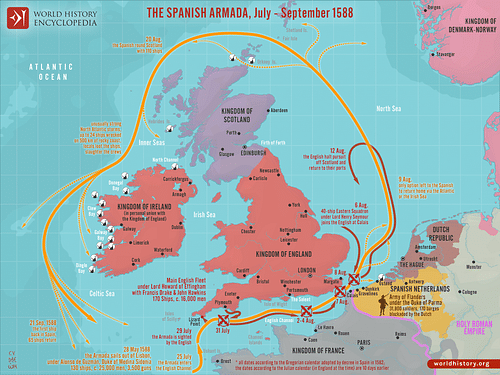

Facing storms, the Armada was obliged to first make for the port of Coruña and so it took two months to finally reach the English Channel. By this time, the invasion was no surprise to the English who spotted the Spanish galleons off the coast of Cornwall on 19 July. Fire beacons spread the news along the coast and, on 20 July, the English fleet sailed from its homeport of Plymouth to meet the invaders. There were about 50 fighting ships on each side and there would be three separate engagements as the navies battled each other and storms. These battles, spread over the next week, were off Eddystone, Portland, and the Isle of Wight. The English ships could not take advantage of their greater manoeuvrability or the superior knowledge of tides of their commanders as the Spanish adopted their familiar disciplined line-abreast formation - a giant crescent. The English did manage to fire heavily at the wings of the Armada, 'plucking their feathers' as Lord Howard put it (Guy, 341). Although the English fleet outgunned the Spanish, both sides found themselves with insufficient ammunition and commanders were obliged to be frugal with their volleys. The Spanish prudently retreated to a safe anchorage off Calais on 27 July having lost only two ships and suffered only superficial damage to many others.

Six fireships, organised by Drake, were then sent into the Spanish fleet on the night of 28 July. Strong winds blew the unmanned ships into the anchored fleet and quickly spread the devastating flames amongst them. The English ships then moved in for the kill off Gravelines off the Flemish coast on 29 July. The Spanish fleet broke its formation still having lost only four ships but many more were now badly damaged by cannon shots. Even worse, 120 anchors had been hastily cut and lost in order to escape the fire ships. The loss of these anchors would be a serious hindrance to the manoeuvrability of the Spanish ships over the coming weeks. The Armada was then hit by the increasingly strong winds from the south-west. The Duke of Medina Sidonia, unable to get close enough to grapple and board with the flighty English ships and with Parma's force blockaded in by Dutch ships, ordered a retreat and abandonment of the invasion.

God hath given us so good a day in forcing the enemy so far to leeward as I hope in God that the Prince of Parma and the Duke of Sidonia shall not shake hands these few days; and whensoever they shall meet, I believe neither of them will greatly rejoice of this day's service.

(Ferriby, 226)

The Armada was forced by the continuing storm to sail around the tempestuous and rocky shores of Scotland and Ireland in order to return home. Several English ships pursued the Spanish to Scotland but the bad weather and unfamiliar coastlines did the real damage. Stores quickly ran out, horses were thrown overboard, ships were wrecked, and those mariners who escaped to shore were handed over to the authorities for execution. There was another bad storm in the Atlantic, and only half of the Armada made it back to Spain in October 1588. Incredibly, England was saved. 11-15,000 Spaniards had died compared to around 100 Englishmen.

Tilbury

Meanwhile, Elizabeth visited her land army in person, gathered at Tilbury in Essex in order to defend London should the Armada make landfall. Another English army had been stationed on the north-east coast and a mobile force followed the Armada as it had progressed along the English coast. The army at Tilbury, consisting of infantry and cavalry totalling 16,500 men, was to have been led by the queen's favourite Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester (l. c. 1532-1588) but he was too unwell to do so. Elizabeth, wearing armour and riding a grey gelding, roused her troops with the following celebrated speech:

My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes for fear of treachery, but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear…I always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good will of my subjects, and therefore I am come amongst you as you see me at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live or die amongst you all, to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and for my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust.

I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and a king of England too, and think it foul scorn that Parma or Spain or any Prince of Europe, should dare invade the borders of my realm, to which, rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field. I know already for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns; and we do assure you, on the word of a Prince, they shall be duly paid to you…By your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over these enemies of God, of my kingdom and of my people.

(Phillips, 122)

Aftermath

Philip did not give up despite the disaster of his great 'Enterprise', and he tried twice more to invade England (1596 and 1597) but each time his fleet was repelled by storms. The Spanish king also supported rebellions in Catholic Ireland by sending money and troops in 1601, as he had done prior to the Armada in 1580. On the other side, Elizabeth sanctioned the failed counterattack on Portugal in 1589. A mix of private and official ships and men, this expedition had confused aims and so achieved nothing. In essence, the queen then continued to favour defence over attack as the backbone of her foreign policy. In addition, high taxes were needed to pay for the war with Spain and this was a burden that added to the many others the English people had to endure, such as rises in inflation, unemployment and crime, all of which went on top of a run of bad harvests.

The defeat of the Spanish Armada did give England a new confidence and showed the importance of sea power and modern cannon firepower. A well-armed fleet with well-trained crews could extend the power of a state far beyond its shores and seriously damage the supply lines of its enemies. This was perhaps the most lasting legacy of the Armada's defeat. The Tudors had both built and now thoroughly tested the foundations of the Royal Navy which under the next ruling dynasties would grow ever-bigger and sail on to change world history from Tahiti to Trafalgar.