A Sutra (Sanskrit for “thread”) is a written work in the belief systems of Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism which is understood to accurately preserve important teachings of the respective faiths and guide an adherent on the path from ignorance and entrapment in the endless cycle of rebirth and death (samsara) toward spiritual liberation.

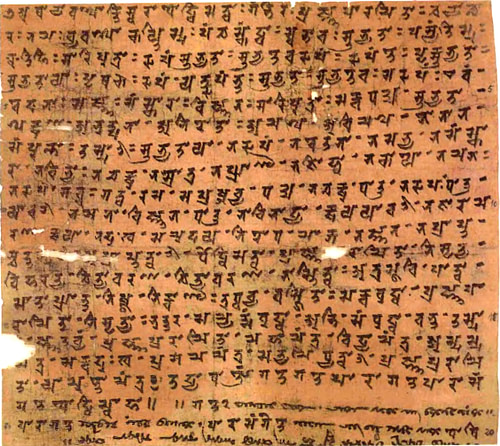

A sutra is, therefore, regarded as an integral aspect of the scripture of these respective faiths. The works are known as sutras because, like a thread (or twine or string), they bind in written form a previously oral tradition. The term was almost certainly also initially descriptive since the works were written on leaves or pressed bamboo slats which were then bound together with thread.

The Hindu Vedas were preserved in oral form before being committed to writing during the Vedic Period (c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE) and so were the scriptures of Jainism, known as the Agamas, whose written form dates from the 6th-3rd centuries BCE, with later sutras dating up through the 5th century CE, and those of Buddhism from the 1st century BCE - 6th century CE. Most sutras fit the above definition of authoritative representations of the original words of foundational sages, but a number are manuals on how one should conduct one's self, on political matters, or relate criticism and commentary on various other subjects.

Hinduism (known by adherents as Sanatan Dharma, “Eternal Order”) maintains that it has no founder and its tenets were relayed by Brahman, creator of the universe and the Universe itself, who spoke the Vedas (knowledge) directly to humanity and its sutras, a part of the Vedas, are therefore considered wholly divine in origin. The sutras of Jainism purport to preserve the original teachings of the 24th tirthankara (“ford builder”), the sage Vardhamana (better known as Mahavira l. c. 599-527 BCE). The Jain sutras are also known as suyas and provide adherents with the essential guidelines for navigating a meaningful life toward the goal of liberation. The sutras of Buddhism (also known as suttas) follow the same paradigm in that they are understood as the authentic words of the sage Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha, l. c. 563 - c. 483 BCE) which were memorized by one of his closest disciples and later committed to writing to preserve his vision.

The sutras of each faith have informed the belief systems from generation to generation down through the ages and are still referred to for guidance and proper understanding. Each of these belief system's sutras differ, sometimes significantly, from each other but their essential message is the same: humans are held in bondage through ignorance of the true nature of existence and, by freeing one's self from this bondage, one can attain complete spiritual liberation and break the cycle of rebirth and death.

Ignorance of the true nature of life and one's self causes the soul to experience repeated incarnations in a physical body which must suffer sickness, loss, old age, and death and blinds one to transformative possibilities; the sutras serve as a kind of handbook guiding one toward recognition of a higher, and more meaningful, life. The works have been copied and preserved multiple times, in many different languages, since they were first committed to writing and still serve to guide adherents in the present day.

Hinduism & the Nastika Schools

As noted, Hinduism claims to have no founder as its tenets are said to have been first transmitted from the Universe directly to humanity. According to the belief system, the entity known as Brahman – creator and overseer of the universe and the Universe itself – set all things in motion and maintains them. Brahman is recognized as far too overwhelmingly majestic to be comprehended by a mortal mind, however and, remaining remote but still wishing for contact with humans, placed a divine spark of itself within each individual.

This spark is known as the atman, and each person's atman links the individual to all other humans and all other living things as well as to Brahman. The purpose of life, according to Hinduism, is to be faithful to one's dharma (duty), a responsibility no one else can perform, in accordance with one's karma (right action) in order to escape from the cycle of rebirth and death and attain oneness with one's atman, which then draws one naturally back to unity with Brahman.

This knowledge of the Eternal Order and the nature of life was spoken by Brahman in vibrations which were “heard” by Indian sages of the ancient past who preserved them in oral form. During the Vedic Period, these “vibrations” were committed to writing as the Vedas. At some point around 600 BCE, a general upheaval of social, political, and religious thought occurred in India which led some religious thinkers and reformers to question the basic tenets of Hinduism and its practices.

The Vedas, after all, were written in Sanskrit – a language the common people could not understand – and so were interpreted for them by the Hindu clergy who lived at a level of luxury far above the common lot. Further, the Hindu priests told the people that whatever they might be suffering or think they were suffering, it was all a part of the Eternal Order and no one should complain.

This perceived injustice led to a reformation movement, which resulted in a splintering of orthodox Hinduism. Many different schools were established which either agreed with the Hindu vision or dispensed with it to create their own. Those schools which recognized the divine authority of the Vedas were known as astika (“there exists”) while those which rejected orthodoxy and embraced heterodoxy were known as nastika (“there does not exist”). The three nastika schools which received the most attention and attracted the most followers were Charvaka, Jainism, and Buddhism.

Charvaka, founded c. 600 BCE by the reformer Brhaspati, completely rejected the supernatural aspects of Hinduism and claimed that direct, personal experience was the only way of establishing truth. The Charvakan school, emphasizing materialism as reality, also maintained that anything that was not able to be apprehended by the senses did not exist, that the observable elements of air, earth, fire, and water are all that do exist, that religion is an invention of the strong to control the weak, and that the pursuit of one's personal understanding of pleasure is the meaning and goal of life.

Charvakan emphasis on the practical and empirical would influence the development of the scientific method in India and open possibilities for advancement in many fields which would never have been explored by the earlier orthodox theism which informed the thoughts of the people. The school's insistence on pleasure for pleasure's sake as the end goal in life, and its denial of an afterlife of rewards and punishments, failed to meet the needs of the people, however, and led to its decline. No Charvaka sutras have ever been discovered, and all that is known of the philosophy comes from later Buddhist and Jain texts which denounce it.

Hindu Sutras

Hindu sutras, on the other hand, are well known and have exerted a powerful influence on the lives of adherents, and world spirituality since they were first committed to writing. According to Hindu belief, that which Brahman originally spoke is known as Shruti (“what is heard”) and applies to the Vedas. Other texts, including the sutras, are known as Smritis (“what is remembered”) in that they preserve the concepts, teachings, and interpretations relating to the Vedas by earlier sages. There are a significant number of Hindu sutras and, owing to considerations of space, only a few will be discussed here.

Brahma Sutras: Composed between c. 200 BCE and 200 CE, the earliest form of this text is attributed to the sage Badarayana, associated with Veda Vyasa, the traditional author of the great Indian epic Mahabharata. The Brahma Sutras discuss the fundamental nature of Brahman, provide commentary on the Upanishads, and criticize unorthodox schools of thought such as Buddhism, Jainism, Samkhya, and Yoga. It is the foundational text of the Vedanta school of Hinduism, one of the six astika schools formed after c. 600 BCE, and maintains the orthodox Hindu tradition of the Vedic Period.

Nyaya Sutras: Composed c. 300 BCE by the Vedic sage Gautama, this text comprises the view of another of the early astika schools, the Nyaya, whose primary focus was epistemology: how one knows what one knows. The work presents the four pramanas (ways of establishing truth/foundations of knowledge): sense perception, inference, comparison, testimony of an expert. The Nyaya school was primarily responsible for turning people away from Buddhism by debating Buddhist teachers publicly and defeating them.

Yoga Sutras: Composed between c. 100 BCE - c. 500 CE and attributed to the sage Patanjali, this is the classic text on the philosophy and practice of yoga (“discipline”). There are many different kinds of yoga other than hatha yoga (which most people, especially in the West, know as “yoga”) such as jian yoga (intellectual discipline) or bhakti yoga (devotional discipline). The Yoga Sutras are the foundational text of the Yoga Darshana (philosophy of yoga) and the most popular of the Hindu sutras overall.

Samkhya Sutra: The date of composition is unknown as it is attributed to the Vedic sage Kapila (dates unknown but possibly c. 620 BCE), founder of the astika school of Samkhya which emphasized rationalism and the duality of spirit and matter. Samkhya philosophy informs Yoga and so the Samkhya Sutra is often paired, with the Yoga Sutra in that the former establishes the spiritual condition and the latter addresses how one responds to it. Kapila, whose philosophy may have influenced the Buddha's later thought, introduced the concept of the three qualities of the soul to Hinduism known as the gunas (Sattva=Wisdom; Rajas=Passion; Tamas=Confusion), which became central to the belief system.

Kama Sutra: Composed c. 300 BCE by the sage Vatsyayana, the Kama Sutra is another of the best-known Hindu texts in the West. Although it is often wrongly referenced as an esoteric “sex manual”, it is actually a treatise on the spiritual value of erotic love, sensory pleasure as a divine gift, and romantic attachment as a means to higher understanding and personal fulfillment.

Jain Sutras

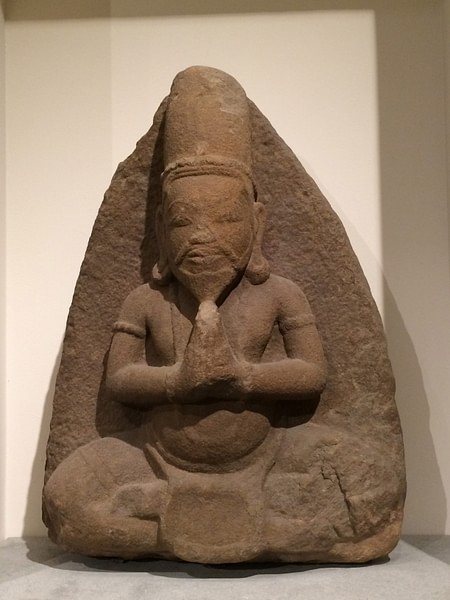

Jainism maintains an ancient and divine origin on par with Hinduism, also claiming that its basic tenets were first “heard” by sages long ago who are known as tirthankaras. A tirthankara (“ford builder”) is an enlightened soul who constructs spiritual “bridges” over the difficult aspects of existence, enabling others to cross over them and pursue the spiritual discipline which will release them from the suffering of samsara and grant liberation. The 24th tirthankara to appear from the time of the first revelation was Mahavira, and the Jain sutras contain his teachings.

There are a number of Jain sutras which are regularly consulted by adherents such as the Chedasutras, Culikasutras, Malasutras, and Prakinasutras, but the foundational text is the Tattvartha Sutra (composed 2nd-5th centuries CE) which presents and expounds upon the essential vision of Mahavira including the Five Vows and the Seven Truths. Jainism redefines the Hindu concept of karma as action to mean karma as physical entrapment. The soul attracts karmic particles, becomes incarnated, believes it is the physical body it inhabits, and suffers accordingly, blindly subjecting itself to endless incarnations on the wheel of samsara.

The Tattvartha Sutra presents the Seven Truths one must recognize to begin the process of awakening:

- Jiva: The soul exists

- Ajiva: Non-sentient matter exists

- Aasrava: Karmic particles exist which are attracted to the soul

- Bandha: These karmic particles adhere to the soul and cause incarnation

- Samvar: The attraction of karmic particles to the soul can be stopped

- Nirjara: Karmic particles can be caused to fall away from the soul

- Moksha: Liberation from bondage is achieved once karmic particles are released

After recognizing the Seven Truths, one commits to the Five Vows:

- Ahimsa (non-violence)

- Satya (speaking the truth)

- Asteya (non-stealing)

- Brahmacharya (chastity or faithfulness to a spouse)

- Aparigraha (non-attachment)

The Jain adherent then proceeds through 14 spiritual steps which lead the individual, under the guidance of the teachings of the tirthankara, to liberation. At the end of one's path, one either dies and is freed from rebirth or remains to teach others and become a "ford builder".

Buddhist Sutras

Buddhism was founded by Siddhartha Gautama, traditionally understood to have been a Hindu prince who became disillusioned with the ephemeral nature of life and renounced his position to pursue a spiritual path, leading to his enlightenment. Upon attaining awareness, he understood that people suffered (and so bound themselves to the wheel of endless suffering through samsara) because they failed to understand that the nature of life was constant change. In trying to hold on to ever-changing experiences as permanent states, one trapped one's self in a cycle of craving and fear which one could free one's self from through acknowledgement of the Four Noble Truths and the spiritual discipline of the Eightfold Path.

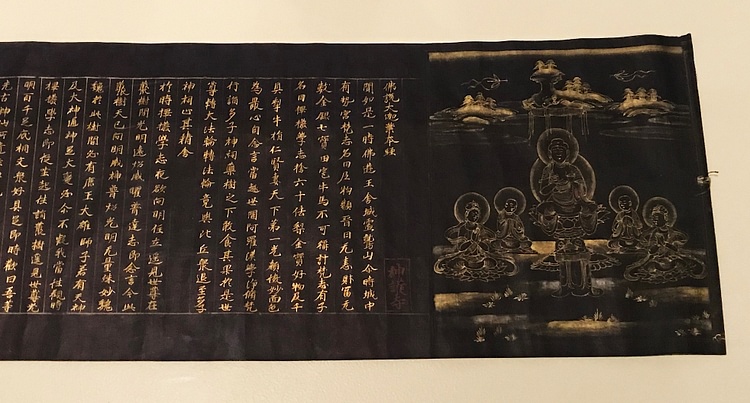

The canonical scriptures of Buddhism, written by the Buddha's students after his death, are known as the Tripitaka (“three baskets”) because they are made up of three categories of teachings: the Vinaya, the Sutta Pitaka, and the Abhidhamma which, respectively, address monastic life and conduct, the teachings of the Buddha, and commentary/analysis of those teachings. Other Buddhist sutras comment on or explain aspects of the Tripitaka or address and expand upon the core beliefs it expresses.

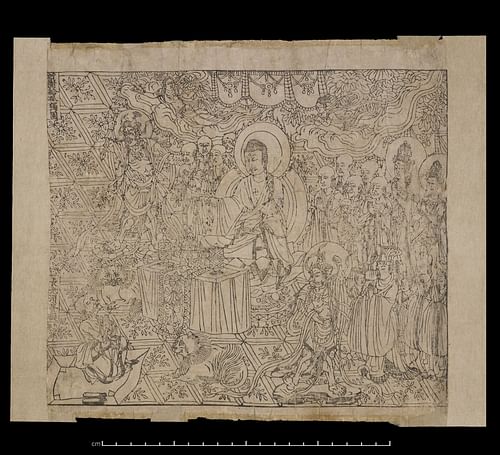

As with the other two belief systems, there are many Buddhist sutras but the best-known is the foundational text of a collection of 38 sutras under the title Prajnaparamita – Perfection of Wisdom. These sutras were composed between c. 50 BCE - c. 600 CE and the two most famous are the Diamond Sutra and the Heart Sutra. The Diamond Sutra derives its name from a line of the Buddha's in which he states that the discourse should be so named because it will cut through ignorance like a diamond. The work addresses the difference between what one perceives as reality and true reality as well as how definitions of aspects of reality separate one from actual reality. Calling a piece of furniture with a flat surface and four legs a “table”, for example, prevents one from seeing the true nature of that object; one labels it a “table”, becomes comfortable with that definition, and never recognizes its true nature could be something different. In the same way, labels which are applied to anything separate one from true reality. The Diamond Sutra, like the rest of the works in Perfection of Wisdom, seeks to engage a reader fully in discarding accepted illusions and awakening to full awareness.

The Heart Sutra, composed c. 660 CE, is a summary of the earlier sutras which distills their meaning to present a focused treatise on the importance of discarding illusion and recognizing truth. The Heart Sutra is the most popular and widely read Buddhist work, regularly recited, in whole or in part, by Buddhists of the Mahayana school who often memorize long passages from it. Through a series of dialogues, the work draws an audience toward the experience known as sunyata (“clear vision”), a state of mind in which one can rightly tell reality from illusion and is liberated from the ignorance which imprisons the soul and causes one to suffer.

Conclusion

The reformist efforts of the nastika schools succeeded in establishing wholly new belief systems but Hinduism retained its hold on the religious imagination of the majority of the populace. The efforts of the Nyaya school, especially, dissuaded many from accepting Buddhist and Jain doctrines and Buddhism remained a small philosophical sect until it was embraced by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka the Great (r. 268-232 BCE) who not only popularized the Buddha's teachings in India, but sent missionaries to spread his vision to other countries including Sri Lanka, China, Korea, and Thailand where it became far more popular than it had been (or remains even now) in its homeland.

Chinese Buddhists embarked on pilgrimage to India, and some, such as the famous traveler Xuanzang (l. 602-664 CE), translated numerous Buddhist sutras into Chinese and brought them back to China. Among these was the Diamond Sutra, which was later printed from wooden blocks of text pressed to paper in 868 CE, pre-dating the Gutenberg Bible by centuries and establishing the Diamond Sutra as the first known printed book in the world.

Although the sutras of Hinduism and Jainism have exerted their own significant levels of influence outside of India, Buddhist sutras are the most widely known simply because of its adoption by so many people of other nationalities. The works of all three religions complement each other, however, far more than they disagree on the essential message of ignorance as the foundation of human suffering and compassion as the first step toward a meaningful life and liberation from illusion.