Tarquinia (Etruscan name: Tarch'na or Tarch, Roman name: Tarquinii) is a town located on the western coast of central Italy which was an important Etruscan and then Roman settlement. It is famous today as the site of around 200 Etruscan tombs which were rich in artefacts and decorated with magnificent wall paintings showing lively scenes from mythology and Etruscan everyday life. The tombs are designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

EARLY SETTLEMENT & MYTHOLOGY

The site of modern Tarquinia (formerly Corneto), or Tarch(u)na as it was known to the Etruscans, is today located on a plateau some 6 km from the central Italian coast, 90 km north of Rome. Excavations in the 19th century CE revealed that the site was inhabited in the Late Bronze Age, and from the 9th century BCE, by the Iron Age culture known as the Villanovan, a precursor of the Etruscans.

According to Etruscan mythology, the city was founded by Tarchon, grandson of Hercules and the son of Tyrrhenus, the king of the Tyrrhenian Sea. The site was also the spot where Tages, the wise child, sprang from the earth. This legendary figure was revealed when a field near Tarquinia was being ploughed and he showed Tarchon, or the 12 Etruscan priests called the lucumones, the art of divination through reading omens and animal entrails, and how to maintain contact with the gods (Etrusca Disciplina). It is interesting to note that archaeologists have discovered a 9th-century BCE child burial at the site which was the subject of a long cult, and this may perhaps be a physical link to the myth of Tages.

A THRIVING ETRUSCAN CITY

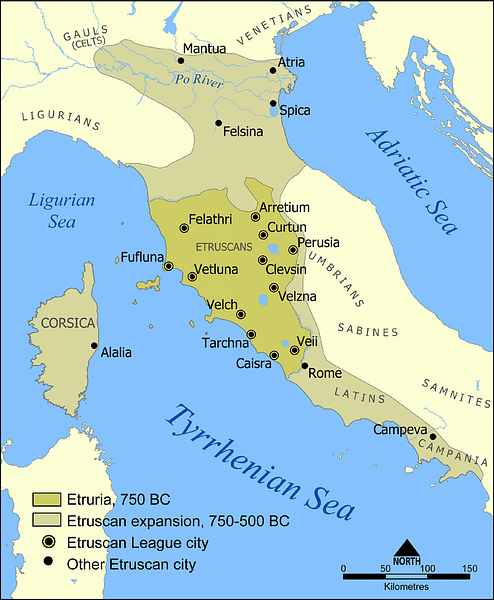

Tarquinia became the most important of the 12 (or perhaps 15) Etruscan towns which formed the loose confederacy known as the Etruscan League. Very little is known of the league except that its members had common religious ties and leaders met annually at the Fanum Voltumnae sanctuary near Orvieto (exact location as yet unknown). The other members of the league included Cerveteri (Cisra), Chiusi, Populonia, Vulci (Velch), and Volterra. The precise workings of Tarquinia's political structure are not known beyond that it was first a monarchy and then likely had a government dominated by the aristocrats of the city.

Tarquinia's prosperity from the 8th century BCE was based on its role as a trade centre and the presence of rich mineral deposits nearby. Fertile land was put to good use for agriculture, especially the cultivation of olives and vines. Goods were manufactured and exported such as bronze work, gold jewellery, and linen. A wealthy elite was formed as testified by large and handsomely decorated tombs. One resident, Demaratus of Corinth, who was the father of Rome's King Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, indicates the cultural links with Greece at that time. A port was established at Gravisca and goods were imported and exported across the Mediterranean, especially with Greek cities, Phoenician traders, and, later, Carthage. Greek Art, especially the Eastern Greek or Ionian style, was especially influential on Etruscan art and can be seen both in the tomb wall-paintings of Tarquinia and in the appreciation of Greek art objects such as fine black-figure pottery, found in abundance in the city's tombs.

Continuing to flourish in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, the city constructed large fortification walls (10 km in total length), a temple, and impressive chamber tombs. The temple, built in the 4th century BCE on the site of an earlier structure and known by the later name of the Ara della Regina (Altar of the Queen), was dedicated to an unknown god or goddess (although a votive bronze rod found there was dedicated to Artemis). Terracotta winged horses were added to the building in the 4th century BCE.

Etruscans cities, in general, suffered a partial decline between 450 and 350 BCE when Syracuse gained control of the lucrative local shipping routes. Tarquinia did recover somewhat, but a new and more deadly threat approached from the southern horizon: the Romans. Initially, treaties were signed between the two cultures, but as the Romans expanded, they realised that the weak political alliance of the Etruscan cities made them ripe for conquest. Indeed, the Etruscan cities were known to have fought each other in long-standing rivalries for regional dominance. An ongoing war against Rome ensued with atrocities on both sides – notably the sacrifice of 307 Roman prisoners in the forum in 356 BCE, which brought a retaliation murder of 358 Tarquinian prisoners in Rome.

In 281-280 BCE Etruria finally fell under Roman control, and in 181 BCE, a Roman colony was founded at Gravisca. In 89 BCE Tarquinia was demoted to the status of a municipium, but its inhabitants were by now granted the right of Roman citizenship. A slow slide into obscurity followed, and Tarquinia was abandoned in the medieval period with the population shifting to nearby Corneto, which would eventually change its name to Tarquinia.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS

The Monterozzi cemetery has Etruscan remains and, beneath these, evidence of an extensive Villanovan settlement. The remains of the 4th-century BCE temple are located on the Pian di Civita. It is the largest known Etruscan temple with a surviving limestone blocks base measuring 77 x 34 m. The temple was of Tuscan design, with side walls protruding at the front and an access ramp flanked by steps on the east side. The inner cella had three chambers at the rear. Pieces of its decorative sculpture also survive, including a charioteer with a lance and, also in terracotta, reliefs of two winged horses and fragments of a goddess which was part of a plaque placed over a beam-end of one of the pediments.

Other artefacts excavated from the site include painted marble sarcophagi and bronze hand mirrors which are engraved with scenes on the back (especially of myths). These mirrors typically had wood, bone, or ivory handles and were a symbol of status in Etruscan society. Another artefact common to Tarquinia is relief slabs. Carved from the local nenfro stone, they have scenes showing figures embracing, dancing, dining, and scenes from mythology, usually in pairs of figures separated by decorative frames. The slabs were perhaps used as tomb markers.

There are many examples of the Etruscan bucchero wares with its shiny dark grey surface and bronze work such as vessels and tripods. Finally, there is a series of 1st-century CE Latin inscriptions, known as the Elogia Tarquiniensia, which describes the lives of the city's most celebrated citizens. The inscriptions were carved on marble slabs and placed on the pediments of a statue of the person described.

THE TOMBS OF TARQUINIA

The earliest tombs at Tarquinia date from the late 7th century BCE. In total, there are 6,000 tombs, around 200 of which had painted interior walls. They constitute the largest pre-Roman tomb complex from antiquity, and many of the chambers therein are decorated with colourful and lively wall paintings. They are an invaluable source of information on Etruscan daily life and religious practices. The paintings are applied to a thin base layer of plaster wash with the artists first drawing outlines using chalk or charcoal.

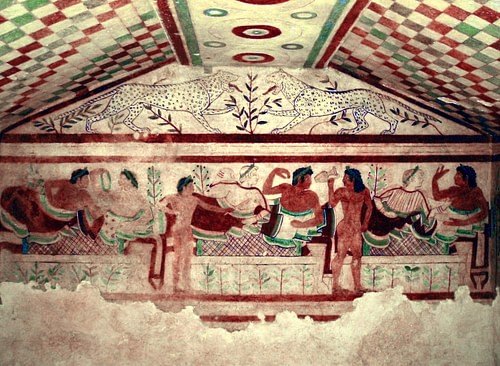

The earliest tombs are rectangular rock-cut chambers which are painted to replicate the architectural features of real houses. Others have ceilings painted to mimic tent fabric, alluding to the earlier Etruscan practice of using tents to cover the deceased. Mythical creatures are commonly painted on pillars, and banquet scenes near the ceilings. Later tombs have false doorways and more ambitious painted scenes covering entire walls, especially scenes showing diners reclining on couches, drinkers on mats, Dionysiac revelry, hunting, games, and figures bidding a fond farewell to the deceased.

The Tomb of the Bulls, dating to 540-530 BCE, is a typical example and has the name of its occupant painted on one wall: Aranth Spurianas. The tomb has a central chamber leading to two smaller rooms. Painted scenes include Achilles attacking Troilos, the young Trojan prince. A frieze above this scene shows two copulating couples (one heterosexual trio and one homosexual couple) and two bulls. Another wall in the tomb has the myth of Bellerophon and Pegasus, with the hero riding a horse and facing the Chimera and a sphinx. Finally, there is a scene of a young man riding a hippocamp (mythical seahorse) over the ocean, perhaps as a metaphor for the tomb occupant's journey into the next life.

The misleadingly named Tomb of the Lionesses, built 530-520 BCE, actually has two painted panthers, a large drinking party scene, and is interesting for its unusual checkered pattern ceiling and six painted wooden columns. There is also a fine frieze of dolphins, birds, palmettes, and lotus flowers. The Tomb of the Augurs (c. 520 BCE) has a scene of two nude wrestlers – named as Teitu and Latithe, and probably slaves – while between them lie three bowls, the prizes for the victor. There is also a representation of a figure who appears in several other tombs, Phersu - a man wearing a black-bearded mask who holds a ferocious dog on a long leash, which attacks a man whose head is wrapped in a cloth. This may be a scene of prisoner execution.

The Tomb of The Baron (named after its discoverer Baron Kestner), dating to c. 510 BCE, has various human figures either standing or riding, and these include a woman caught in the act of saying farewell, presumably to the tomb's occupant. Contemporary with this tomb is the Cardarelli Tomb (named after a local poet), which has a scene of a woman, wearing a flowing cape and red pointed shoes, accompanied by a slave girl and boy, the latter carrying a fan. Other figures include two nude boxers, dancers, and musicians.

The c. 480 BCE Tomb of the Bigas has a representation of athletic games and a chariot (bighe) race, watched by a crowd of spectators, imaginatively drawn with some figures in three-quarter view and others foreshortened to provide perspective. The Tomb of the Dying and Tomb of the Dead Man (c. 470 BCE) are unusual in that they actually portray the occupant laid out on their deathbed surrounded by mourning relatives. Finally, the Tomb of the Blue Demons (420-400 BCE) gives a rare glimpse of the Etruscan vision of the Underworld, here inhabited by blue- and black-skinned demons, one of which holds two snakes, but there are also the more welcoming, already dead relatives of the tomb's occupant, awaiting the family's reunification in the afterlife.