The Theodosian Walls are the fortifications of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire, which were first built during the reign of Theodosius II (408-450 CE). Sometimes known as the Theodosian Long Walls, they built upon and extended earlier fortifications so that the city became impregnable to enemy sieges for 800 years. The fortifications were the largest and strongest ever built in either the ancient or medieval worlds. Resisting attacks and earthquakes over the centuries, the walls were particularly tested by Bulgar and Arab forces who sometimes laid siege to the city for years at a time. Sections of the walls can still be seen today in modern Istanbul and are the city's most impressive surviving monuments from Late Antiquity.

Making the City Safe

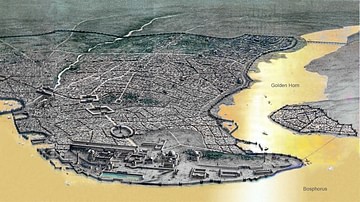

Although the city had benefitted from previous emperors building fortifications, especially Constantine I when he moved his capital from Rome to the east, it is Emperor Theodosius II who is most associated with Constantinople's famous city walls. It was, though, Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) who began the project of improving the capital's defences by building the Golden Gate of Constantinople in November 391 CE. The massive gate was over 12 metres high, had three arches, and a tower either side. It was entirely built of marble and decorated with statues and was topped with a sculpture of a chariot pulled by four elephants. The Golden Gate probably marked the start of triumphal processions which ended in the Hippodrome. Two decades later, Theodosius II was alarmed at the recent fall of Rome to the Goths in 410 CE and set about building a massive line of triple fortification walls to ensure Constantinople never followed the same fate. The man credited with supervising their construction is Theodosius' Praetorian Prefect Anthemius. The walls extended across the peninsula from the shores of the Sea of Marmara to the Golden Horn, eventually being fully completed in 439 CE and stretching some 6.5 kilometres. They expanded the enclosed area of the city by 5 square kilometres.

Design & Architecture

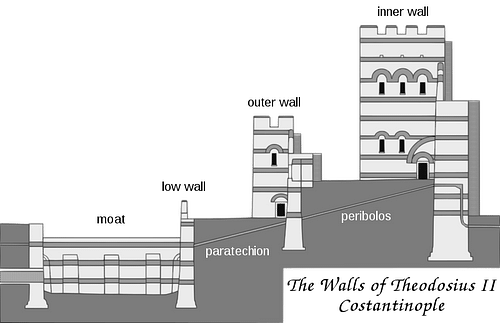

The defensive walls were made of a combination of elements designed to make the city impregnable. Attackers first faced a 20-metre wide and 7-metre deep ditch which could be flooded with water fed from pipes when required. The water, once in, was retained by a series of dams. Behind that was an outer wall which had a patrol track to oversee the moat. Behind this was a second wall which had regular towers and an interior terrace so as to provide a firing platform to shoot down on any enemy forces attacking the moat and first wall. Then, behind that wall was a third, much more massive, inner wall. This final defence was almost 5 metres thick, 12 metres high, and presented to the enemy 96 projecting towers. Each tower was placed around 70 metres distant from another and reached a height of 20 metres. The towers, either square or octagonal in form, could hold up to three artillery machines. The towers were so placed on the middle wall so as not to block the firing possibilities from the towers of the inner wall. The inner wall was constructed using bricks and limestone blocks while the outer two were built from mixed rubble and brick courses with a limestone facing. Access to the city when not under attack, besides via the Golden Gate, was provided by ten additional gates.

The walls were built on a rising embankment so that the defenders could easily fire down on the structures in front of them if necessary. The plan of the fortifications ensured that the enemy could not place their siege engines anywhere near the all-important inner wall, and even artillery fire from a distance was presented with a much more limited target than in more traditional, single-wall fortifications. The distance between the outer ditch and inner wall was 60 metres while the height difference was 30 metres. A formidable obstacle indeed, especially when the defenders also had their secret weapon, the incendiary liquid known as “Greek Fire” which could be poured down upon or fired in grenades at the attackers. Defenders were organised according to the factions of the Hippodrome of the city. The four supporter groups were also responsible for the upkeep of the walls. By stocking up on food, rounding up livestock and with plenty of water in the city's massive cisterns, Constantinople was ready to withstand all comers.

Significant Sieges

The city was severely tested several times in its long history but the massive walls never let down the capital's inhabitants. There was an unsuccessful siege in 626 CE by the army of Persian king Kusro II helped by his Slav and Avar allies. One of the most persistent attacks came with the Arab siege of 674-678 CE when the walls withstood siege engines and artillery fire from massive catapults. Another Arab siege came in 717 CE, this time an all-year-round affair involving 1,800 ships and an army of 80,000 men. Rumours of the approaching army provoked the Byzantine emperor into insisting that any family without three-years' worth of provisions flee the city. In the end, the harsh winter did more harm to the attackers than the defenders, and Constantinople survived yet again. The next to try his luck was Thomas the Slav, who besieged the capital in 821 CE but, predictably, the city held on. In 860 CE, 941 CE, and 1043 CE Russian attacks proved as ineffectual as any that had gone before.

Finally, after 800 years, the city's defences were breached by the knights of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 CE, although the attackers got in through a carelessly left-open door and not because the fortifications themselves had failed in their purpose. Byzantine emperor Michael VIII (r. 1261-1282 CE) rebuilt the fortifications in the 1260s CE, but they could not withstand a second successful attack on them when the walls suffered severe damage from Ottoman canon fire in 1453 CE.

Large parts of the Theodosian Long Walls, including many towers, can still be seen today in Istanbul, where portions have been significantly restored. The Golden Gate still stands, too, as it was made part of the castle treasury of Mehmed II in 1453 CE.