The Upanishads are the philosophical-religious texts of Hinduism (also known as Sanatan Dharma meaning “Eternal Order” or “Eternal Path”) which develop and explain the fundamental tenets of the religion. The name is translated as to “sit down closely” as one would to listen attentively to instruction by a teacher or other authority figure.

At the same time, Upanishad has also been interpreted to mean “secret teaching” or “revealing underlying truth”. The truths addressed are the concepts expressed in the religious texts known as the Vedas which orthodox Hindus consider the revealed knowledge of creation and the operation of the universe.

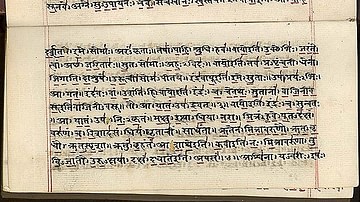

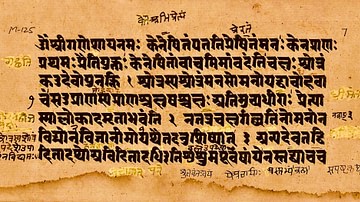

The word veda means “knowledge” and the four Vedas are thought to express the fundamental knowledge of human existence. These works are considered Shruti in Hinduism meaning “what is heard” as they are thought to have emanated from the vibrations of the universe and heard by the sages who composed them orally before they were written down between c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE. The Upanishads are considered the “end of the Vedas” (Vedanta) in that they expand upon, explain, and develop the Vedic concepts through narrative dialogues and, in so doing, encourage one to engage with said concepts on a personal, spiritual level.

There are between 180-200 Upanishads but the best known are the 13 which are embedded in the four Vedas known as:

- Rig Veda

- Sama Veda

- Yajur Veda

- Atharva Veda

The Rig Veda is the oldest and the Sama Veda and Yajur Veda draw from it directly while the Atharva Veda takes a different course. All four, however, maintain the same vision, and the Upanishads for each of these address the themes and concepts expressed. The 13 Upanishads are:

- Brhadaranyaka Upanishad

- Chandogya Upanishad

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- Aitareya Upanishad

- Kausitaki Upanishad

- Kena Upanishad

- Katha Upanishad

- Isha Upanishad

- Svetasvatara Upanishad

- Mundaka Upanishad

- Prashna Upanishad

- Maitri Upanishad

- Mandukya Upanishad

Their origin and dating are considered unknown by some schools of thought but, generally, their composition is dated to between c. 800 - c. 500 BCE for the first six (Brhadaranyaka to Kena) with later dates for the last seven (Katha to Mandukya). Some are attributed to a given sage while others are anonymous. Many orthodox Hindus, however, regard the Upanishads, like the Vedas, as Shruti and believe they have always existed. In this view, the works were not so much composed as received and recorded.

The Upanishads deal with ritual observance and the individual's place in the universe and, in doing so, develop the fundamental concepts of the Supreme Over Soul (God) known as Brahman (who both created and is the universe) and that of the Atman, the individual's higher self, whose goal in life is union with Brahman. These works defined, and continue to define, the essential tenets of Hinduism but the earliest of them would also influence the development of Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, and, after their translation to European languages in the 19th century CE, philosophical thought around the world.

Early Development

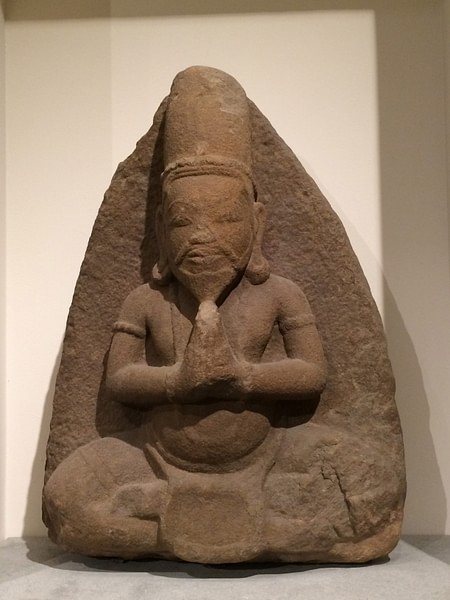

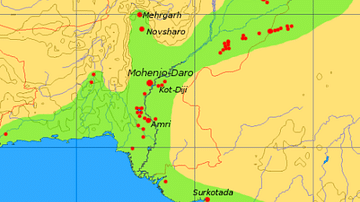

There are two differing claims regarding the origin of Vedic thought. One claims that it was developed in the Indus Valley by the people of the Harappan Civilization (c. 7000-600 BCE). Their religious concepts were then exported to Central Asia and returned later (c. 3000 BCE) during the so-called Indo-Aryan Migration. The second school of thought, more commonly accepted, is that the religious concepts were developed in Central Asia by the people who referred to themselves as Aryans (meaning “noble” or “free” and having nothing to do with race) who then migrated to the Indus Valley, merged their beliefs and culture with the indigenous people, and developed the religion which would become Sanatan Dharma. The term 'Hinduism' is an exonym (a name given by others to a concept, practice, people, or place) from the Persians who referred to the peoples living across the Indus River as Sindus.

The second claim has wider scholarly support because proponents are able to cite similarities between the early religious beliefs of the Indo-Iranians (who settled in the region of modern-day Iran) and the Indo-Aryans who migrated to the Indus Valley. These two groups are thought to have initially been part of a larger nomadic group which then separated toward different destinations.

Whichever claim one supports, the religious concepts expressed by the Vedas were maintained by oral tradition until they were written down during the so-called Vedic Period of c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE in the Indo-Aryan language of Sanskrit. The central texts of the Vedas themselves, as noted, are understood to be the received messages of the Universe, but embedded in them are practical measures for living a life in harmony with the order the Universe revealed. The texts which deal with this aspect, which are also considered Shruti by orthodox Hindus, are:

- Aranyakas – rituals and observances

- Brahmanas – commentaries on the rituals

- Samhitas – benedictions, mantras, prayers

- Upanishads – philosophical dialogues in narrative form

Taken together, the Vedas present a unified vision of the Eternal Order revealed by the Universe and how one is supposed to live in it. This vision was developed through the school of thought known as Brahmanism which recognized the many gods of the Hindu pantheon as aspects of a single God – Brahman – who both caused and was the Universe. Brahmanism would eventually develop into what is known as Classical Hinduism, and the Upanishads are the written record of the development of Hindu philosophical thought.

Central Concepts of Upanishads

Brahman was recognized as incomprehensible to a human being, which is why It could only be apprehended even somewhat through the avatars of the Hindu gods, but was also understood as the Source of Life which had given birth to humanity (essentially each person's father and mother). It was recognized as impossible for a mere human to come close to the enormity which was Brahman but seemed equally impossible for Brahman to have created people to suffer this kind of separation from the Divine.

The Vedic sages solved the problem by shifting their focus from Brahman to an individual human being. People obviously moved and ate food and felt emotions and saw sights but, the sages asked, what was it that enabled them to do these things? People had minds, which caused them to think, and souls, which caused them to feel, but this did not seem to explain what made a human being a human being. The sages' solution was the recognition of a higher self within the self – the Atman – which was a part of Brahman each individual carried within. The mind and soul of an individual could not grasp Brahman intellectually or emotionally but the Atman could do both because the Atman was Brahman; everyone carried a spark of the Divine within them and one's goal in life was to reunite that spark with the source from which it had come.

The realization of the Atman led to the obvious conclusion that duality was an illusion. There was no separation between human beings and God – there was only the illusion of separation – and, in this same way, there was no separation between individuals. Everyone had this same divine essence within them, and everyone was on the same path, in the same ordered universe, toward the same destination. There is, therefore, no need to look for God because God is already dwelling within. This concept is best expressed in the Chandogya Upanishad by the phrase Tat Tvam Asi – “Thou Art That” – one is already what one wants to become; one only has to realize it.

The goal of life, then, is self-actualization – to become completely aware of and in touch with one's higher self – so that one could live as closely as possible in accordance with the Eternal Order of the Universe and, after death, return home to complete union with Brahman. Each individual was thought to have been placed on earth for a specific purpose which was their duty (dharma) which they needed to perform with the right action (karma) in order to achieve self-actualization. Evil was caused by ignorance of the good and the resulting failure to perform one's dharma through the proper karma.

Karma, if not discharged correctly, resulted in suffering – whether in this life or one's next – and so suffering was ultimately the individual's own fault. The concept of karma was never intended as a universal deterministic rule which fated an individual to a set course; it always meant that one's actions had consequences which led to certain predictable results. The individual's management of his or her own karma led one to success or failure, satisfaction or sorrow, not any divine decree.

The transmigration of souls (reincarnation) was considered a given in that, if a person failed to perform their dharma in one life, their karma (past actions) would require them to return to try again. This cycle of rebirth and death was known as samsara and one found liberation (moksha) from samsara through the self-actualization which united the Atman with Brahman.

The Principal Upanishads

These concepts are explored throughout the Upanishads which develop and explain them through narrative dialogues which Western scholars often equate to the philosophical dialogues of Plato. Some scholars have criticized the interpretation of the Upanishads as philosophy, however, arguing that they do not present a cohesive train of thought, vary in focus from one to the next, and never arrive at a conclusion. This criticism completely misses the point of the Upanishads (and, actually, Plato's work as well) as they were not created to provide answers but to provoke questions.

The interlocutors in the dialogues are sometimes between teacher and student, sometimes husband and wife, and in the case of Nachiketa in the Katha Upanishad, between a youth and a god. In every case, there is someone who knows a truth and someone who needs to learn it. An audience is encouraged to identify with the seeker who wants to learn from the master and, in doing so, is forced to ask the seeker's same questions of themselves: Who am I? Where did I come from? Why am I here? Where am I going?

The Upanishads have already answered these questions in the phrase Tat Tvam Asi, but one cannot realize that one already is what one wants to become without doing the personal work to discover who one is as opposed to who one thinks one is. The Upanishads encourage an audience to explore their inner landscape through interaction with the characters who are doing the same thing.

There is no narrative continuity between the different Upanishads, though each one has its own to greater or lesser degrees. They are given here in the order in which they were composed with a brief description of their central focus.

Brhadaranyaka Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda and the oldest Upanishad. Deals with the Atman as the Higher Self, the immortality of the soul, the illusion of duality, and the essential unity of all reality.

Chandogya Upanishad: Embedded in the Sama Veda, it repeats some of the content of the Brhadaranyaka but in metrical form which gives this Upanishad its name from Chanda (poetry/meter). The narratives further develop the concept of Atman-Brahman, Tat Tvam Asi, and dharma.

Taittiriya Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda, the work continues on the theme of unity and proper ritual until its conclusion in praise of the realization that duality is an illusion and everyone is a part of God and of each other.

Aitareya Upanishad: Embedded in the Rig Veda, the Aitareya repeats a number of themes addressed in the first two Upanishads but in a slightly different way, emphasizing the human condition and joys in a life lived in accordance with dharma.

Kausitaki Upanishad: Embedded in the Rig Veda, this Upanishad also repeats themes addressed elsewhere but focuses on the unity of existence with an emphasis on the illusion of individuality which causes people to feel separated from one another/God.

Kena Upanishad: Embedded in the Sama Veda, the Kena develops themes from the Kausitaki and others with a focus on epistemology. The Kena rejects the concept of intellectual pursuit of spiritual truth claiming one can only understand Brahman through self-knowledge.

Katha Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda, the Katha emphasizes the importance of living in the present without worrying about past or future and discusses the concept of moksha and how it is encouraged by the Vedas.

Isha Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda, the Isha focuses emphatically on unity and the illusion of duality with an emphasis on the importance of performing one's karma in accordance with one's dharma.

Svetasvatara Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda, the focus is on the First Cause. The work continues to discuss the relationship between the Atman and Brahman and the importance of self-discipline as the means to self-actualization.

Mundaka Upanishad: Embedded in the Atharva Veda, focuses on personal spiritual knowledge as superior to intellectual knowledge. The text makes a distinction between higher and lower knowledge with “higher knowledge” defined as self-actualization.

Prashna Upanishad: Embedded in the Atharva Veda, concerns itself with the existential nature of the human condition. It focuses on devotion as the means to liberate one's self from the cycle of rebirth and death.

Maitri Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda, and also known as the Maitrayaniya Upanishad, this work focuses on the constitution of the soul, the various means by which human beings suffer, and the liberation from suffering through self-actualization.

Mandukya Upanishad: Embedded in the Athar Veda, this work deals with the spiritual significance of the sacred syllable of OM. Detachment from life's distractions is stressed as important in realizing one's Atman.

Any one of the Upanishads offers an audience the opportunity to engage in their own spiritual struggle to apprehend Ultimate Truth but, taken together along with the Vedas, they are thought to elevate one above the distractions of the mind and daily life toward higher levels of consciousness. The more one engages with the texts, it is claimed, the closer one comes to Divine knowledge. This is encouraged by the paradox of the inherently rational, intellectual, nature of the discourses contrasted with repeated emphasis on rejecting rational, intellectual attempts at apprehending truth. Divine Truth could only finally be experienced through one's own spiritual work. This aspect of the Upanishads would influence the development of Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism.

Conclusion

The Upanishads informed the development of Hinduism solely until they were translated into Persian under the reign of the prince Dara Shukoh (also given as Dara Shikoh, l. 1615-1659 CE), son and heir of the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan (r. 1628-1658 CE, best known for building the Taj Mahal). Dara Shukoh was a liberal Muslim and patron of the arts who believed the Upanishads transcended the vision expressed by any religion and, in fact, informed all. He, therefore, presented the works as “secret teachings” which revealed the final truths of existence.

The Upanishads were later translated into Latin by the great French philologist and Orientalist Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron (l. 1731-1805 CE) who first brought them to the attention of European scholars in 1804 CE. The first translation into English was done by the British Sanskrit scholar and Orientalist Henry Thomas Colebrooke (l. 1765-1837 CE) who translated the Aitareya Upanishad in 1805 CE. At about this same time, the Indian reformer Ram Mohan Roy (l. 1772-1833 CE) was translating the works from Sanskrit into Bengali as part of his initiative to demystify Hinduism and return it to the people in what he considered its proper form.

Through these efforts, the Upanishads drew considerable attention throughout the early part of the 19th century CE until they were championed by the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (l. 1788-1860 CE) who declared them the equal of any philosophical text in the world. Eastern philosophy and religion had already been introduced to the West through the Transcendentalist Movement of the early 19th century CE but Schopenhauer's admiration for the Upanishads encouraged a revival of interest which became more pronounced when 20th-century CE writers began drawing on the Upanishads in their work.

The American poet T.S. Eliot (l. 1888-1965 CE) used the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad in his masterpiece The Wasteland (1922 CE), introducing the work to an entirely new generation. The Upanishads would become more popular, however, after the 1944 CE publication of the novel The Razor's Edge by the British author Somerset Maugham (l. 1874-1965 CE) who used a line from the Katha Upanishad as the epigraph to the book and the Upanishads as a whole as central to the plot and development of the main character.

The writers and poets of the Beat Generation of the 1950s CE would continue to popularize the Upanishads in their works and this trend continued through the 1960s CE. In the present day, the Upanishads are recognized as among the greatest philosophical-religious works in the world and continue to engage a modern audience as fully as they have those of the near and ancient past.