Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552-1618 CE) was an English courtier, soldier, mariner, explorer, and historian. A one-time favourite of his queen, Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE), Raleigh organised three expeditions to form a colony on the coast of North America in the 1580s CE. The colony was abandoned but the expeditions were notable for introducing tobacco and the potato to England. Unsuccessful at colonisation and falling out with his queen when he married one of her ladies-in-waiting, Raleigh turned instead to finding El Dorado, the fabled golden city of South America. Once more, success was elusive. Back in England, the adventurer was accused of treason by King James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE) and imprisoned in the Tower of London for 13 years. Writing poetry and an important work of history, the beached mariner was improbably freed in 1616 CE to explore one last time South America. This final expedition was another failure and led once again to imprisonment. Raleigh was executed in the Tower in 1618 CE.

Early Life

Walter Raleigh (or Ralegh as he himself preferred) was born c. 1552 CE in Devon, the son of a member of the local gentry. Educated at Oxford University, Walter volunteered to serve in France to assist the Huguenots there against Catholic oppression. Moving on to Ireland in the mid-1570s CE and establishing a plantation there, Walter was a young captain involved in putting down the Irish rebellions against English colonialism. Raleigh hardly covered himself in glory, though, when he participated in the massacre of 600 surrendered Italian troops at Smerwick in 1580 CE.

From 1581 CE Raleigh arrived at court and his family connection to Elizabeth I's childhood nurse was a helpful point of introduction to his monarch. He made a positive impression with his height, good looks and quick wit. Although 20 years her junior, Raleigh's charm and poetry soon attracted the good favour of his queen. Polite and chivalrous - at least in outward form, Raleigh's eccentricity is illustrated by the likely fictional story that he once lay down his cloak upon a puddle so that the queen need not get her feet wet. Raleigh's good relationship with Elizabeth was helped by his position as captain of the Yeoman Guard which gave him more access to his queen than most. The relationship thus had practical and often lucrative consequences. Over time, Raleigh accumulated large estates in the southwest, Midlands and Ireland which went along with his political influence as a Member of Parliament for Devon and Cornwall. He was given royal monopolies for tin and playing cards, and licences for taverns for 30 years. Rich and proud of showing it, critics once quipped that Raleigh's jewelled shoes alone cost a ridiculous £6,000. The pinnacle came when he was knighted in 1585 CE. All this social progress came despite the rumour Raleigh was said to have denied the immortality of the soul and questioned Elizabeth's foreign policy as not aggressive enough; Raleigh once joked, "Her Majesty did all by halves" (Guy, 289). Perhaps, for this very reason, Raleigh was never admitted to the Privy Council, England's executive seat of government.

Virginia & the Roanoke Colony

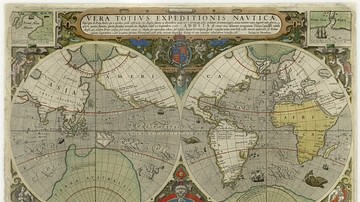

Raleigh's early colonial career was more as an armchair traveller when he masterminded three expeditions to the New World without ever going in person. First, Raleigh acquired from his queen a six-year patent to create a colony in North America. The 1584 CE Amadas-Barlowe Expedition was formed to investigate what is today North Carolina, USA to see if this was suitable territory for England's first colony. Friendly contact with the Native Americans was made on Roanoke Island, and it did seem a fertile land with commodities available via trade such as skins and pearls.

Raleigh organised his second expedition in 1585 CE and this time a small fleet captained by Richard Grenville (1542-1591 CE) carried a number of settlers, all men, and led by Ralph Lane (d. 1603 CE). Landing on Wokokan Island, the settlers then moved to nearby Roanoke Island but their provisions were limited and the Roanoke Indians were reluctant to trade with the Europeans as they had little surplus themselves. By the following spring, relations had soured and Lane attacked the Roanokans' village (perhaps as a preemptive strike), killing their chief. The settlers were relieved to leave for England in June 1586 CE when Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE) passed by on his way back from a raid in the Caribbean. Back in England, the showing of novelties such as tobacco and potatoes convinced investors to back Raleigh's plans for a third expedition to the land he had named in honour of his queen: Virginia.

The 1587 CE expedition aimed to establish a colony for its own sake and not in order to form a base from which to attack Spanish ships in the Caribbean. Accordingly, the ships carried another group of settlers but this time included families, who were led by the experienced painter and cartographer John White (d. 1593 CE). White painted the colony, wildlife and Native Americans of the region, creating an invaluable pictorial record which still survives today. Hoping to settle in the Chesapeake Bay area, White was obliged by storms to settle again on Roanoke Island in July. The indigenous peoples had not forgotten Lane's attack the previous year and after the ships had sailed back to England, it seems likely the settlers were killed. The exact fate of the Europeans is not known as a relief ship could not be sent to them until August 1590 CE. No trace of the settlers was found except the word 'Croatoan' carved on a tree. This was the name of an island to the south but storms prevented any investigation at the time, hence the Roanoke Colony became known as the 'Lost Colony'. It was not an auspicious start for English colonial plans but it was a beginning and would be followed up with more successful expeditions in the 17th century CE; Raleigh had shown the way.

Marriage & Fall from Grace

Although he became a firm favourite of his queen, Elizabeth was often susceptible to jealousy if any of her male courtiers showed interest in other women. Raleigh's star, already a little less glittering because of the Roanoke failure, plummeted in August 1592 CE when the queen imprisoned Raleigh in the Tower of London for a month. Elizabeth had discovered that in November of the previous year Raleigh had married without her knowledge and fathered a son. Even worse, Raleigh's wife, Elizabeth 'Bess' Throckmorton (1565 - 1647 CE), was a lady-in-waiting at court, and she soon joined her husband in his confinement.

Raleigh was often involved in the privateering that helped fill adventurers' pockets and Elizabeth's state coffers whenever loot was taken from Spanish treasure ships sailing from the New World back to Europe. Raleigh now saw this as the best way to restore relations with his sovereign. Indeed, the most celebrated capture ever made was in 1592 CE when a fleet of ships partly bankrolled by Raleigh - he had wanted to lead them in person but the queen recalled him to his confinement in London - won the Battle of Flores in the Azores and captured the Portuguese Madre de Deus (aka Madre de Dios). Portugal was at the time ruled by Philip II of Spain, and the Madre de Deus was actually coming from the East Indies. The ship, crewed by up to 700 men and bristling with 32 cannons, was no sitting duck, but on 3 August, it was attacked and captured by the fleet of English vessels.

The Madre de Deus was packed full of valuable cargo that included diamonds, rubies, gold and silver coins, pearls, fine cloth, ebony, pepper and spices. The ship was the single richest prize ever taken by Elizabeth's privateers and was sailed triumphantly into Dartmouth on 9 September. Despite much pilfering by English parties and squabbles amongst the multiple investors of the whole enterprise, Raleigh managed to sell-off the more cumbersome goods still left in the ship's hold and so Elizabeth got more than her fair share, perhaps around £80,000 worth on her original investment of £3,000.

Back in the queen's good books (almost), Raleigh was released from the Tower in September 1592 CE but forbidden to see the queen for a year. Elizabeth Throckmorton was never forgiven and obliged to live a retired life at Raleigh's home in Sherborne, Dorset. The couple's first son, Damerai, had died aged one of plague, but they did have a second son, Walter (Wat), who was born in 1593 CE. A third son, Carew, was born in 1605 CE.

In Search of El Dorado

The failure of the Roanoke Colony and necessity to restore his position at court may have pushed Raleigh to try exploration firsthand. Accordingly, in 1595 CE Raleigh set off on his own adventures, this time his goal was to find the fabled city of gold: El Dorado. The name means 'Gilded Man' or 'Golden One' and actually refers to the coronation ceremony of kings of the Muisca civilization (600-1600 CE) in modern Colombia. In the ceremony held at Lake Guatavita, the king was plastered with resin and then covered in gold dust before he dived into the waters. This tradition became garbled in translation and the fables that reached the Spanish Conquistadors convinced them there was a city paved with gold somewhere in the remote northern Andes. The Spanish tried and failed to find El Dorado but Raleigh wished to now make his own attempt.

Raleigh arrived first in Trinidad and from there he explored the Orinoco River in what is today Venezuela and Guiana. Progress was halted by formidable waterfalls and they found nothing more remarkable than pineapples, which Raleigh described as 'the princess of fruits' (Williams, 223). In the sweltering climate, Raleigh employed local guides but was obliged to give up after four weeks and return home empty-handed. A second expedition, this time without Raleigh, was sent to explore the coast of Guiana to see if there were an easier route to the mountainous interior but again no positive results were gained. Raleigh would have to wait 21 years to try again.

Cadiz Raid

In June 1596 CE Raleigh was part of the expedition led by Lord Howard (1536-1624 CE) and the queen's new favourite and Raleigh's great rival, Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex (1567-1601 CE) which attacked and then captured Cadiz, destroying 50 Spanish ships in the process. Cadiz was still Spain's main Atlantic port and the strike was designed as a preemptive one to prevent Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598 CE) forming another Armada with which he might invade England. Raleigh fought with aplomb but was wounded in the action and suffered a limp thereafter. Another English raid on Spanish territory the next year was a dismal failure as storms and disagreement over objectives scuppered the offensive. If Raleigh had had his way, Cadiz would have been garrisoned and might have become a long-term English stronghold on the Continent like Calais had been in the past and Gibraltar would be in the future, but it was not to be.

Second Imprisonment

In 1603 CE, Elizabeth I died without an heir and so her cousin, James VI of Scotland, became the new king of England as James I of England. Immediately, there were plots to dethrone this first of the Stuart kings, and one was said to have involved Raleigh and Lord Cobham, the plan being to replace James with his cousin Lady Anabella Stuart. The plot was discovered, and Raleigh, with powerful enemies at court and accused of treason, was imprisoned in the notorious Bloody Tower of the Tower of London. The adventurer's old rivalry with the late-Earl of Essex had not been helpful as the king had been a frequent correspondent of Robert Devereux. Tried and convicted on trumped-up charges, Raleigh's days were numbered, or so it seemed.

As it turned out, Raleigh would remain in the tower for years. At least he was permitted visits from his family and a number of attendants suitable to his rank. In 1610 CE the king forbade Elizabeth Throckmorton to live with her husband in the Tower, although she was given a modest pension. With time on his hands, Raleigh wrote an ambitious and influential work of history, the History of the World. This sprawling epic was never completed but it became so popular it ran into ten editions, double that of Shakespeare's collected works. The fallen courtier also wrote many other works such as a commentary on contemporary politics, the Dialogue between a Councillor and a Justice of the Peace. Raleigh wrote, too, the Report of the Truth of the Fight about the Isles of Azores which described Richard Grenville's heroic battle captaining the Revenge against a large fleet of Spanish ships in September 1588 CE. Besides experimenting in alchemy, distilling fresh water from seawater, mixing herbal medicines, and finding a way to cure tobacco, the beached adventurer also composed poetry and wrote such poignant verses as these:

Even such is Time, that takes in trust,

Our youth, our joys, and all we have,

And pays us but with earth and dust.

Who, in the dark and silent grave,

When we have wandered all our ways,

Shuts up the story of our days.

And from which earth and grave and dust,

The Lord shall raise me up I trust.

(Jones, 300)

The Final Search for El Dorado

Unexpectedly, Raleigh was at last released from his long confinement in March 1616 CE. His frequent pleas to James I that he should be allowed to try once again to find the treasure of El Dorado had finally swayed the almost bankrupt king. Raleigh was freed and, although under constant supervision, he spent the next year preparing his expedition back to South America. In March 1617 CE Raleigh sailed from Plymouth aboard the aptly named Destiny. Contrary winds and a near-skirmish with a Spanish vessel - when expressly told not to privateer - were ominous signs of worse to come. Disease spread through the ship's crew, afflicting Raleigh, too. The adventurer was so ill he was obliged to remain at the expedition's base on Trinidad while the main party, led by Raleigh's son Wat, explored the Orinoco River. Wat rashly attacked a Spanish village and was killed in the process. There was no El Dorado and no gold. Raleigh was forced to return to England and face the wrath of his king. Many attempts have, of course, since been made to explore Lake Guatavita and even empty it but none have been successful in finding the hoped-for treasure of El Dorado.

On the old adventurer's return home in June 1618 CE, his monarch refused to see him. The attack on the Spanish settlement in Guiana was a highly embarrassing episode just when England and Spain were trying to repair their diplomatic relations. The Spanish ambassador called for Raleigh's head and his fate was sealed. Facing his execution on 29 October 1618 CE, Raleigh denied all the charges against him and declared that he was guilty only of seeking glory for himself and his country. The adventurer conceded he was a "man full of all vanity" who had lived "a sinful life, in all sinful callings, having been a soldier, a captain, a sea-captain and a courtier, which are all places of wickedness and vice" (Bicheno, 319). He met his death with dignity and humour, entertaining the crowd with a few last pleasantries before the axe fell.

Sir Walter Raleigh has become a legendary figure for his achievements, his vision in the potential of the New World, and because of the age in which he lived but as Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626 CE) noted in his mini-biography of Raleigh:

Those who came after him, who never met him, have instinctively liked Raleigh, or their version of Raleigh. He was certainly a most astonishing and compelling man, in his writings as in the rest of his life touched by genius and greatness, the focus of legend. It should not be forgotten, however, that many of those who lived in the small world of the Elizabethan court, after long association with Raleigh, either disliked him intensely or distrusted him profoundly.

(ibid, 300)