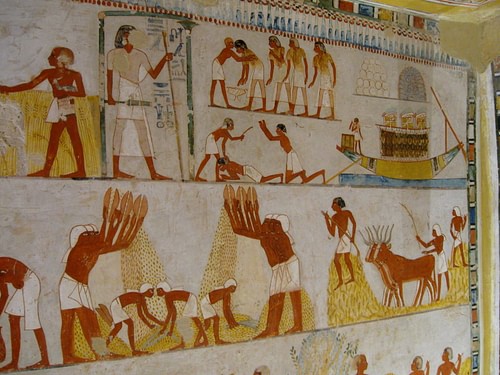

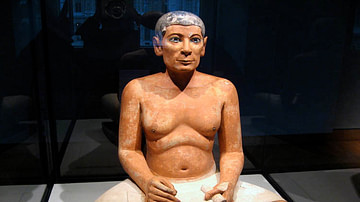

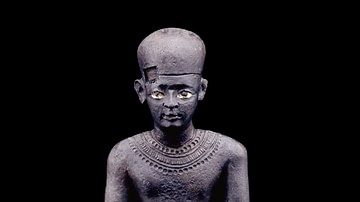

The society of ancient Egypt was strictly divided into a hierarchy with the king at the top and then his vizier, the members of his court, priests and scribes, regional governors (eventually called 'nomarchs'), the generals of the military (after the period of the New Kingdom, c. 1570- c. 1069 BCE), artists and craftspeople, government overseers of worksites (supervisors), the peasant farmers, and slaves.

Social mobility was not encouraged, nor was it observed for most of Egypt's history, as it was thought that the gods had decreed the most perfect social order which was in keeping with the central value of the culture, ma'at (harmony and balance). Ma'at was the universal law which allowed the world to function as it should and the social hierarchy of ancient Egypt was thought to reflect this principle.

The people believed the gods had given them everything they needed, and set them in the most perfect land on earth, and had then placed the king over them as an intermediary between the mortal and divine realms. The primary responsibility of the ruler was to keep ma'at and, when this was accomplished, all the other obligations of his office would fall naturally into place.

An Egyptian monarch could not personally oversee every aspect of the society, however, and so the position of the vizier was created as far back as the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150- c. 2613 BCE). The vizier (a sort of prime minister) delegated responsibilities to other members of the court, sending messages through scribes, and also oversaw the military and the operations of regional governors, public works projects, and tax collections among his many other duties.

At the bottom rung of this hierarchy were the slaves (people who could not pay their debts, criminals, or those taken in wars) and, just above them, the peasant farmers who made up 80% of the population and provided the resources which allowed the civilization to survive and flourish for over 3,000 years.

The Rise of the Gods & the Cities

As far as we know, human habitation in the Sahara Desert region dates back to c. 8000 BCE and these people migrated toward the Nile River Valley to settle in the lush region known as the Fayum (also Faiyum). A farming community was established in this area as early as c. 5200 BCE and pottery has also been found in the same region dating to 5500 BCE. It should be noted that these dates relate only to established agrarian communities, not to the initial human habitation of the Fayum region which dates to c. 7200 BCE.

The Fayum in c. 5000 BCE was a lush paradise in which the people would have enjoyed fairly comfortable lives with abundant water and natural resources. At some point around 4000 BCE, however, a drought seems to have changed these ideal living conditions. The waters dried up and the wildlife moved on to find a more suitable environment.

The people who had established themselves in the region migrated toward the Nile River Valley and left the Fayum basin relatively deserted. These people then formed the communities which grew into the early Egyptian cities along the Nile River. This migration falls within the era known as the Predynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000- c. 3150 BCE) before the establishment of a monarchy.

At this time, it is thought the people formed themselves into tribes for protection against the environment, wild animals, and other tribes and one of their most important defenses against all these dangers was a belief in the protective power of their personal gods. Egyptologist and historian Margaret Bunson comments on this:

The Egyptians lived with forces that they did not understand. Storms, earthquakes, floods, and dry periods all seemed inexplicable, yet the people realized acutely that natural forces had an impact on human affairs. The spirits of nature were thus deemed powerful in view of the damage they could inflict on humans. (98).

In the same way that people recognized the ability of these forces to injure, however, they also believed the same could protect and heal. This early belief in supernatural forces was expressed in three forms:

- Animism - the belief that inanimate objects, plants, animals, and the earth have souls and are imbued with the divine spark;

- Fetishism - the belief that an object has consciousness and supernatural powers;

- Totemism - the belief that individuals or clans have a spiritual relationship with a certain plant, animal, or symbol.

In the Predynastic Period, animism was the primary understanding of the universe, as it was with early people in most cultures. Bunson writes, "Through animism humankind sought to explain natural forces and the place of human beings in the pattern of life on earth" (98). In time, animism led to the development of fetishism through the creation of symbols (such as the djed or ankh) which both represented a higher concept and had its own innate powers.

Fetishism then branched into totemism through the development of specific spiritual forces which watched over and guided an individual, a tribe, or community. Once totemism became the accepted understanding of how the world worked, these forces were anthropomorphized (given human characteristics) and these became the gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt.

These deities provided the foundation for the culture for the next 3,000 years. The gods had created the world, all the people in it, and established everything on the principle of harmony and balance. Ma'at was established at the creation of the world, empowered by heka (magic), and so harmony was valued in Egyptian culture as the defining concept of a stable and productive life.

If one were living in balance, according to the will of the gods, one would enjoy a full life and, just as importantly, would contribute to the joy and success of one's community and, by extension, the country. Everyone benefited from knowing their place in the universe and what was expected from them and it was this understanding which gave rise to the social structure of the civilization.

The Social Classes

As with most if not all civilizations from the beginning of recorded history, the lower classes provided the means for those above them to live comfortable lives, but in Egypt, the nobility took care of those under them by providing jobs and distributing food. Since the king represented the gods, and the gods had created the world, the king officially owned all the land. In keeping with ma'at, however, he could not just take from the people whatever he pleased but received goods and services through taxation. Taxes were levied and collected through the offices of the vizier and, once stored, these goods were then redistributed back to the people.

The jobs of the upper class are well known. The king ruled by delegating responsibility to his vizier who then chose the best people beneath him for the necessary tasks. Bureaucrats, architects, engineers, and artists carried out domestic building projects and the implementation of policies, and the military leaders took care of defense. The priests served the gods, not the people, and cared for the temple and the gods' statues while doctors, dentists, astrologers, and exorcists dealt directly with clients and their needs through their skills in magic and application of medicines.

One needed to work if one wanted to eat, but there was no shortage of jobs at any time in Egypt's history, and all labor was considered noble and respectable. Therefore, this redistribution was not a “handout” or charity but fair wages for one's labor. Egypt was a cashless society until the coming of the Persians in 525 BCE and so trade was conducted through the barter system based on a monetary unit known as the deben.

There was no actual deben coin but a deben represented the universally accepted monetary unit used to set the value of a product. If a woven mat cost one deben and a quart of beer cost the same, the mat could be traded fairly for the beer. Workers were regularly paid in beer for a day's labor as beer was considered healthier to drink than the waters of Egypt and was more nutritious but people were also paid in bread, clothing, and other goods for their work.

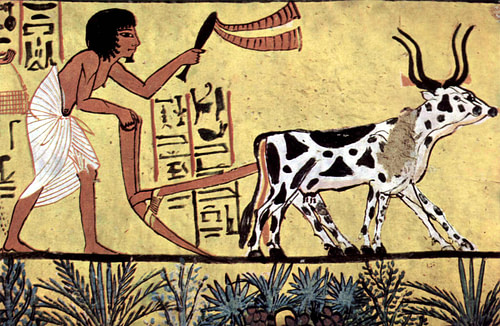

The details of the people's jobs are known from medical reports on the treatment of injuries, letters, and documents written on various professions, literary works (such as The Satire of the Trades), tomb inscriptions, and artistic representations. This evidence presents a comprehensive view of daily work in ancient Egypt, how the jobs were done, and sometimes how people felt about their work. The Egyptians seem to have felt pride in their work no matter their occupation. Everyone had something to contribute to the community, and no skills were considered non-essential. The potter who produced cups and bowls was as important to the community as the scribe, and the amulet-maker as vital as the doctor.

Part of making a living, regardless of one's special skills, was taking part in the king's monumental building projects. Although it is commonly believed that the great monuments and temples of Egypt were achieved through slave labor - specifically that of Hebrew slaves - there is absolutely no evidence to support this claim. The pyramids and other monuments were built by Egyptian laborers who either donated their time as community service or were paid for their labor.

From the top of the hierarchy to the bottom, everyone understood their place and what was required of them for their own success and that of the kingdom. During most of Egypt's history this structure was adhered to and the culture prospered. Even during those eras known as “intermediate periods” – in which the central government was weak or even divided – the hierarchy of the society was recognized as unchangeable because it was so obvious that it worked and produced results. Toward the end of the New Kingdom, however, the system began to break down as those at the top began neglecting those at the bottom and members of the lower classes lost faith in their king.

Deterioration of the Hierarchy

The king's primary duty was to uphold ma'at and maintain the balance between the people and their gods. In doing so, he needed to make sure that all of those below him were well cared for, that the borders were secure, and that rites and rituals were performed according to the accepted tradition. All of these considerations provided for the good of the people and the land as the king's mandate meant that everyone had a job and knew their place in the hierarchy of society. This hierarchy, however, began to break down toward the end of the reign of Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE) when the bureaucracy which helped maintain it floundered due to lack of resources.

Ramesses III is considered the last good pharaoh of the New Kingdom. He defended Egypt's borders, navigated the uncertainty of changing relations with foreign powers, and had the temples and monuments of the country restored and refurbished. He wanted to be remembered in the same way that Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) had been - as a great king and father to his people – and early in his reign he succeeded at this.

Egypt under Ramesses III, however, was not the supreme power it had been under Ramesses II and the country Ramesses III ruled over had suffered a loss in status with attendant diminishing resources from tribute and trade. These problems were caused by the expense of mounting a defense against the invasion by the Sea Peoples in 1178 BCE as well as well as the costs of maintaining the provinces of the Egyptian Empire.

Still, for over 20 years Ramesses III had done his best for the people and, as he approached his 30th year, plans were set in motion for a grand jubilee festival to honor him. The problem was that, unlike in the past, there simply were not the resources available to mount such an elaborate festival. In order to provide Ramesses III with his celebration, the needs of someone else further down the hierarchy would have to be sacrificed; this “someone else” turned out to be the highly-paid tomb workers at Deir el-Medina outside of Thebes.

These workers were among the most respected and well-compensated artisans in Egypt. They built and decorated the tombs of the kings and other nobility and, since these were considered the eternal homes of the deceased, those who worked on them were held in high esteem. In 1159 BCE, three years before Ramesses III's festival, the monthly wages of these workers arrived almost a month late. The scribe Amennakht, who also seems to have served as a kind of shop steward, negotiated with local officials for the distribution of corn to the workers but this was only a temporary solution to a serious problem: the failure of an Egyptian monarch to maintain balance in the land.

Instead of looking into what had caused the problem with delivery of the worker's wages, and trying to prevent it from happening again, officials continued on as though nothing was wrong in preparation for the grand festival. The payment to the workers at Deir el-Medina was again late and then again until, as Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson writes, “the system of paying the necropolis workers broke down altogether, prompting the earliest recorded strikes in history.” (335). The workers had waited for 18 days beyond their payday and refused to wait any longer. They lay down their tools and marched on Thebes to demand what they were owed.

The officials at Thebes had no idea how to deal with this crisis because nothing like it had ever happened before. It was simply impossible, in their experience, for workers to refuse to do their jobs – much less mobilize and march on their superiors. After a number of insufficient remedies were attempted (such as trying to placate the workers by serving them pastries), the government found the means to pay them and the strike ended. The problem had not been resolved, however, and payment to the tomb workers would be late again in the coming years.

The strike of the tomb workers is significant because it signaled the beginning of the end of the belief system which supported the Egyptian hierarchy. The tomb workers were right in their protest: the king had failed them and, in so doing, had failed to maintain ma'at. It was not the job of these workers to recognize and uphold ma'at for the king – quite the reverse – and once balance was lost at the top of the hierarchy, faith was lost by those who made up the far more substantial base.

This is not to claim that Egyptian society fell apart following the tomb worker's strike of 1159 BCE. The hierarchy would continue in its traditional form throughout the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE) and on until Rome annexed Egypt in 30 BCE. Even though the social structure remained the same, however, the understanding of ma'at and the belief in the supremacy and divine nature of the king had changed and never fully regained its former strength in later periods.

This loss of faith affected the cohesion of the society and contributed to the further breakdown of the bureaucracy and the rule of law based on ma'at. Tomb robbing became more commonplace, as was corruption among police, priests, and government officials. When the Persians came in 525 BCE they found a very different Egypt than the great power of the days of empire; once the foundational value of ma'at had been breached, all that had been built on it became unstable.