At its fullest extent, the Roman Empire stretched from around modern-day Aswan, Egypt at its southernmost point to Great Britain in the north but the influence of the Roman Empire went far beyond even the borders of its provinces as a result of commerce and population movements. Contrary to popular belief which holds that the Sahara Desert was an impossible obstacle to trade prior to the Middle Ages, the Romans had a robust and dynamic network of connections to Sudanic and Sub-Saharan Africa. Slaves, gold, foodstuffs, and spices were transported from complex urban settlements on the Niger river, onwards to oasis cities in the Sahara, before finally reaching Rome's bustling ports on the coast of North Africa. Going in the opposite direction, gemstones, textiles, and coins reached cities along the fertile banks of the Middle Niger.

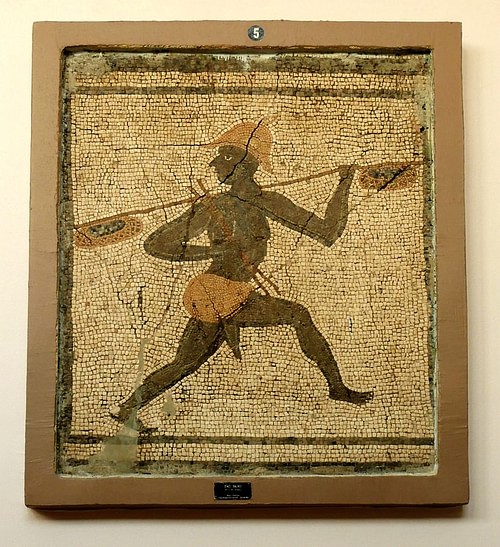

Classical Greek and Roman writers refer to all of Sudanic and Sub-Saharan Africa as 'Aethiopia', while the term 'Africa' originally referred only to the Maghreb region on the northwestern coast of the continent. Most Aethiopians in the Roman Empire likely came from East Africa through Egypt and Nubia but new evidence has also highlighted the role of trade and military interactions between West Africa and the Roman Empire.

Roman Exploration in West Africa

Roman expeditions into the Sahara were well documented beginning in the early Imperial period, though they decreased in Late Antiquity as a result of the accelerating desertification of North Africa. In 19 BCE, the Roman proconsul Cornelius Balbus led a force of 10,000 legionaries into Libya to punish the Garamantes, a Berber people who inhabited the Fezzan region of the Libyan Desert in the northeast Sahara, for rebellious activity. Balbus conquered the city of Ghadames before marching on Garama (Germa) and conquering it. After this, he penetrated the continent further south until reaching what is believed to be the Niger River.

The Roman general Suetonius Paulinus quelled a rebellion in Mauretania in 40 CE, before embarking on a celebrated expedition across the Atlas Mountains and into the Fezzan region of the Sahara (c. 41 CE). In 50 CE a general named Septimius Flaccus led a military expedition against nomadic bandits who were troubling Leptis Magna in modern-day Libya. His expedition proved successful but what was most impressive was that his journey went far further south than the Saharan desert. In fact, Flaccus made it as far as an enormous lake surrounded by elephants and rhinoceroses (Lake Chad) before returning.

According to the 2nd-century CE Alexandrian historian Ptolemy, a Roman merchant named Julius Maternus led an expedition to retread Flaccus' footsteps and open up new trade routes in West Africa. This journey is thought to have been sometime around 83 CE and plotted through what is now Libya to the city of Garama. The Garamantian king allowed Maternus to accompany him on an expedition south and sent letters of introduction to the African kings in the south on behalf of the Roman. Maternus ultimately travelled to Lake Chad before returning to Rome with a two-horned rhinoceros which was displayed in the Colosseum. This animal would have been either a black or white rhinoceros from Central Africa and was a sensation in Rome - due to its performance in the arena. The Roman Emperor Domitian (81-96 CE) was so impressed with the beast and its reception that he minted coins bearing its image sometime between 83 and 85 CE.

SOURCES OF TRADE ON THE NIGER RIVER

Ancient cities and polities in West Africa which had developed along the Middle Niger were participants in the sporadic trans-Saharan trade relations of antiquity. These settlements developed independently in West Africa and are based on a radically different economic, social, and architectural model than the urban centres of Mesopotamia, North Africa, and the Mediterranean. These cities and settlements traded goods like locally grown crops with Saharan contacts for rare foreign imports.

Djenne-Djenno, built near modern-day Djenne, Mali by the Iron Age Nok culture in the early 3rd century BCE, has some of the oldest known evidence of Classical Mediterranean trade in West Africa. Traders in Djenne-Djenno were importing glass beads of Roman or Hellenistic origin as early as the 3rd century BCE. Evidence of trans-Saharan trade has been found in Kissi, Burkina Faso and Dia Shoma, Mali which means that this trade did not deal exclusively with the cities of the Middle Niger but extended to the Niger Bend as well.

Saharan Intermediaries

The extent of trans-Saharan contact between the peoples inhabiting the Sahara desert has long been debated despite the frequent allusions of the Greek and Roman accounts, including sources like The Histories by the 5th-century BCE Greek author Herodotus and Pliny the Elder's 1st-century CE Natural History.

Between the 1st and 4th centuries CE, Rome was trading closely with the Garamante Kingdom, which had become a client state of Rome. Graeco-Roman stereotypes of the Garamantes often dismissed them as unruly nomads:

On its [Libya's] borders dwell the Garamantians, a lightly clad, agile tribe of tent-dwellers subsisting mainly by the chase. (Lucian of Samosata, Dipsas the Thirst-Snake, Ch. 2, translated by Fowler, p. 27)

Archaeologists have uncovered a different picture by demonstrating that they had permanent settlements which were supported by advanced irrigation techniques. Excavations at Garama have revealed a dynamic trade centre with a population of around 10,000.

Mediterranean amphorae containing olive oil and wine as well as imported pottery attest to frequent trade with the Roman Empire. Further evidence of Roman influences comes in the form of Roman-style marble, concrete, and wine presses. Most striking, however, is the presence of a large mausoleum with very clear architectural inspiration from its Roman counterparts.

Carbuncles, Gold & Ancient Grains

One of the most important items that the Garamantes had to offer both Roman and West African traders were semi-precious stones like carnelian and amazonite. These small stones (referred to as carbuncles) were highly prized by Romans and are the primary commodity referenced in literary accounts of this exchange. Carbuncles and other semi-precious stones are the most well-represented objects from the trans-Saharan trade in West Africa. These carbuncles likely acted as a regional commodity and status symbol to locals of the Niger Bend given their rarity and the difficulty involved in obtaining them.

In addition to this, the Garamantes provided the Romans with foodstuffs, exotic Sub-Saharan slaves, and possibly textiles, salt, gold, and ivory in exchange for Roman wine, olive oil, and pottery. Although a large amount of Sub-Saharan goods made it to the Mediterranean, Mediterranean goods did not reach the Sub-Sahara in the same volume. The reason for this was that the Garamantes and other intermediaries tended to keep the expensive Roman products for themselves rather than exchanging them with their contacts in the south. Instead, they provided their West African neighbours with salt, food, and textiles. Glass beads and copper items from the Roman Mediterranean were also traded but only occasionally.

The Garamantes imported a wide range of West African crops like rice, sorghum, cotton, and pearl millet, and some of these crops were cultivated at Garama. Leather and ivory from animals like hippopotami were also imported from Sub-Saharan Africa. Domesticated animals from North Africa such as camels, chickens, and donkeys were first brought across the Western Sahara in the 4th century CE as a result of trans-Saharan trade.

A West African gold trade route is thought to have opened up to the Roman Empire for a brief time during Late Antiquity. Gold ore was mined in the Niger Bend before being transported upriver and ultimately reaching Roman cities in North Africa. The existence of this pre-Islamic gold trade has been reinforced by the fact that Roman gold coin mintage in Carthage and Alexandria only began in 295 CE and lasted until 429 CE when it was disrupted by the Vandal invasion of North Africa. This gold trade explains the appearance of Roman glass, carnelian, and textiles in Kissi, near the Sirba goldfields on the Niger Bend during the late 3rd century CE. This trade was a precursor to the medieval gold trade which was carried out in West Africa by Islamic traders beginning in the 7th century CE.

Archaeological finds of Roman coins in Sub-Saharan Africa are extremely rare but the same is true of Arabic coins, despite the enormous scale of the medieval Islamic trans-Saharan trade. This is largely due to the fact that West African societies did not use a system of minted coinage as currency and so any imported coins would most likely be recirculated back north or melted down for their precious metals.

Slave Trade

More than rice and gemstones were brought north of the Sahara, however, and, in many ways, the movement of people has left a more enduring impact on the archaeological record than gold. Sub-Saharan slaves fulfilled an important role as labourers in Garama, where vast amounts of manpower were needed to maintain the expansive canal systems. Garamantian raiding activity against their Sub-Saharan neighbours may well have been an important source for the trans-Saharan slave trade of antiquity, more so than voluntary exchange. The Garamantes were reported to routinely hunt their southern neighbours from horse-drawn chariots:

These Garamanteans of whom I speak hunt the "Cave-dwelling" Aethiopians [Troglodytes] with their four-horse chariots... (Herodotus, The Histories, Book IV, Ch. 183, translated by Godley p. 387)

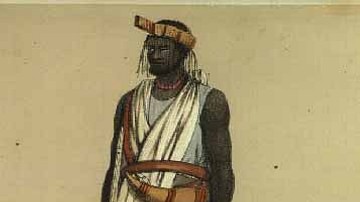

Saharan rock paintings which portray Garamantian chariots have been pointed to as evidence of periodic raids. The Garamantes also exported slaves to their Roman trading partners. Certain “Aethiopians” within the Roman Empire were associated with the Garamantes which implies Roman familiarity with Sub-Saharan Africans in Garamantian society. These slaves were transported as part of trade caravans which embarked from cities like Garama and travelled through the Sahara to the North African coast.

The Roman trade in Sub-Saharan slaves dealt primarily in children and was conducted through port cities like Alexandria and Roman Carthage before reaching Europe and the Near East. In the Imperial Period, this trade seems to have been heavily weighted towards the Roman sex industry as there were far less expensive sources of slaves for agricultural or other manual labour, such as Italy, Gaul, and the Near East.

While most West Africans in the Roman Empire likely ended up in the Mediterranean as a result of slavery, doubtless others lived within the borders of the empire as free people. “Aethiopians” are known to have served in the Roman military, were living in territories captured by the Romans, and travelled to Roman territories under their own initiative as traders or envoys. Even foreigners originally enslaved by Rome could find themselves freed and enfranchised. “Aethiopian” scholars, soldiers, athletes, and performers are known to have contributed to Roman society based on art, literature, remains, and inscriptions from throughout the Roman world.

A New Perspective on Two Ancient Worlds

In the popular imagination, European and Middle Eastern contact with Sub-Saharan Africa is a relatively recent development but this is clearly not so; the intermittent relationship between the Roman Mediterranean and West Africa discussed above shows how very different cultures attempted to reach far outside the horizons of their known world much earlier than many suppose. Through trade networks like these, ancient civilisations were able to overcome the Sahara desert, one of the greatest natural barriers in the world, an achievement which was rewarded by material and cultural wealth for those involved.