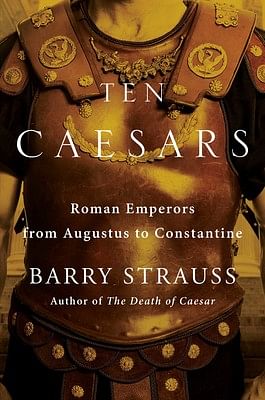

Dr. Barry Strauss' Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine tells the epic story of the Roman Empire from its rise to its eastern reinvention, from Augustus, who founded the empire, to Constantine, who made it Christian and moved the capital east to Constantinople. Highlighting the achievements and legacies of ten Roman emperors, Barry Strauss' new title examines an enduring heritage and legacy that still shapes the Western world today. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Dr. Strauss about the leaders who shaped imperial Roman power and civilization.

JBW: Dr. Strauss, it is always a pleasure to interview you, and I am delighted to learn more about Ten Caesars, which was just published.

What was it that spurred you to write this book?

BS: Ever since watching I, Claudius on PBS' Masterpiece Theatre in the 1970s, I have been fascinated with the personalities of Rome's emperors. They were larger than life, they did great things, and they were very wicked. Writing a book about them is a challenge that I relished. I also believe that the Roman emperors are a tale for our time. As in our era, they had to deal with a large, diverse, and changing society, marked by immigration, and with poverty at home and threats abroad as major challenges.

The emperors did a brilliant job of making friends with change instead of fighting it. They

accepted the evolution of Roman society while preserving those parts of their way of life that they considered essential. They were pragmatists, often ruthlessly so, and sometimes, alas, murderously so.

JBW: How did you select the ten emperors - Augustus (r. 27 BCE-14 CE), Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE), Nero (r. 54-68 CE), Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE), Trajan (r. 98-117 CE), Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE), Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE), Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE), Diocletian (r. 286-305 CE), and Constantine (r. 306-324 CE) - whose lives are examined therein?

BS: Half of them selected me! You could not possibly tell the story without Augustus, Nero, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, and Constantine. Tiberius and Septimius Severus were each key figures and fascinating individuals, so they were easy choices. Vespasian, Trajan, and Diocletian are no less important but it would have been possible to work around them.

I toyed with replacing them with Caligula (r. 37-41 CE), Commodus (r. 177-180 CE), and Aurelian (r. 270-275 CE), but of those three, only Aurelian, I think, compares in interest with Vespasian, Trajan, and Diocletian. Aurelian is the one who got away! By the way, I decided to end with Constantine because Roman history becomes a very different story afterwards.

JBW: I have read in other interviews that Marcus Aurelius is your favorite emperor and Nero is your least favorite. That being acknowledged, I am curious to know, which of the ten emperors in Ten Caesars is the most underrated in your estimation, and why?

BS: Tiberius. He suffers from second-generation syndrome. Augustus is the star who founded the monarchy but it was his successor, Tiberius, who made it last. Like anyone who follows a visionary founder, Tiberius was underrated. Yet it was he who took the ugly but necessary security measures to protect the regime by permanently housing the Praetorian Guard in Rome. It is deplorable that Tiberius had certain senators executed, but maybe it was unavoidable. Maybe more important, Tiberius stopped Rome's expansion.

By pulling back in Germany, he began the process of turning Rome from a conquering empire to an administrative and bureaucratic empire. Tiberius made the Roman monarchy durable but he was rewarded mainly with opprobrium and a lack of deification. He was like a great but underrated ball player who never got into the "Hall of Fame."

JBW: Which primary sources did you consult the most often as you researched this new title? I would imagine it would be the De Vita Caesarum by Suetonius (c. 69-122 CE), but he was rather gossipy like many Roman writers, right?

BS: Suetonius's Lives are gossipy but brilliant and essential. Some of my other most important literary sources are Tacitus (c. 56-120 CE), Josephus (c. 37-100 CE), Pliny the Younger (61-113 CE), Cassius Dio (155-235 CE), Herodian (170-240 CE), and The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. Of course, I read many, many other ancient literary texts in Latin and Greek. I also read a large number of inscriptions, and I consulted a great deal of other material cultural evidence. I was lucky enough to visit quite a few ancient sites.

JBW: Dr. Strauss, you do highlight the importance of various imperial Roman women—the mothers, wives, and mistresses of the emperors—who exercised substantial influence and power over their male counterparts.

BS: On the one hand, Augustus worsened conditions for Roman women because he punished childlessness, celibacy, and adultery (with a free woman, not a slave). He was intent on rebuilding Roman families and population numbers after decades of civil war. Eventually, he even conspicuously punished his own daughter.

On the other hand, Augustus gave extraordinary power to his sister, Octavia (69-11 BCE), and to his wife, Livia (27 BCE-14 CE). He freed both from male guardianship and made them inviolable. Each woman was rich, ran her own household, and even sponsored public buildings. Livia set a trend for elite Roman women by traveling abroad with her husband; the previous practice had been for wives to stay at home. Livia also wielded great influence as one of her husband's advisors. Ultimately Livia's son, Tiberius, inherited the power of his stepfather Augustus and served as his successor. A hostile literary tradition accused Livia of poisoning Augustus' grandsons to remove them from Tiberius' way, but this is surely misogynistic slander. Hostility to a powerful woman is one Roman custom that Augustus did not abolish, unfortunately.

JBW: Is there a woman from the imperial era who most intrigues you and perhaps typifies the imperial Roman era? If so, whom and why?

BS: We might look for a typical Roman woman in, say, Ostia or one of the apartment complexes of capital, or in one of many, many grave inscriptions. I studied elite women in Ten Caesars, of course, and they were not typical. Still, one whose rags-to-riches stories fascinated me is Caenis. She was a slave but she was brilliant and endowed with a photographic memory. She was probably Greek. She served as secretary to the very powerful Antonia the Younger (36 BCE-37 CE), who was the mother of Emperor Claudius and grandmother of Caligula (Gaius). Caenis wrote the letter that Antonia sent to the emperor Tiberius to expose the plot by Sejanus (20 BCE-31 CE), and the result was to save Tiberius and destroy Sejanus.

Later, Antonia freed her. Caenis became the mistress of the talented and ambitious soldier Vespasian. I suspect that she helped him in his rise to power. Later, when he was emperor and a widower, he took Caenis as his common-law wife. She became rich and lived in a luxurious villa in the suburbs of Rome. Supposedly she sold favors and access to the emperor. After her death, her villa was reopened as a set of public baths. One of Caenis' freedmen dedicated a beautiful grave monument to her, including laurel wreaths as a discreet reference to the emperor. Caenis' story opens a fascinating window into social mobility, gender, and power in Imperial Rome in the 1st century CE.

JBW: By the 4th century CE, the Roman Empire had changed so dramatically in its geography, ethnicity, religion, and culture that it would have been virtually unrecognizable to Augustus. However, Constantine's conversion to Christianity is only one facet in the story of the Roman Empire's reorientation eastwards in the 4th and 5th centuries CE.

I suspect much of this had not only to do with the Roman Empire's vast Greek-speaking population and the rise of Christianity but also the military might of Sasanian Persia. Can you tell us more about this complex political, cultural, and economic shift to the east?

BS: Rome's borders were porous, nowhere more so than in the east, where trade and culture traveled both ways. There is an upcoming, terrific new exhibition - The World between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East - about the border region in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, in fact, that I am greatly looking forward to seeing. The East was always the cultural and economic powerhouse of the Roman Empire.

But, as you say, it faced a very serious challenge from Sasanian Persia. The emperors had no choice but to devote an enormous amount of resources to war and diplomacy on the border, although they might have avoided dangerous adventures like Julian's march into Mesopotamia. Persia represented Rome's only peer-polity competitor. The Germanic peoples in the west who challenged Rome were much less well organized. It is ironic, in a way, that the Roman Empire survived in the east and fell in the west.

JBW: Dr. Strauss, aside from adapting when necessary and always persevering no matter the cost, what other lessons can Roman emperors impart in the 21st century CE?

BS: It is a great question, but I have so much to say in response that it is hard to know where to begin, James. Let me make five points:

- Every new boss has to clean house. He or she should do so sharply and swiftly at the outset and then make friends. The opposite, starting out nice and only later going nasty, breeds nothing but opposition. Augustus and Hadrian got it right; Tiberius got it backwards and paid a price for it.

- A successful leader has to have an outstanding and trustworthy second-in-command. Augustus, for example, could never have gained power without Agrippa (c. 64-12 BCE), and keeping power would have been much more difficult without him as well. The same is true, but only more so, when it comes to having a good and supportive wife (or husband). Livia for Augustus, Caenis for Vespasian (a common-law wife but a wife nonetheless), Plotina (d. c. 122) for Trajan, and Julia Domna (160-217 CE) for Septimius Severus, all come to mind.

- The Roman emperors succeeded because they knew how to make change their friend. Let us take diversity. The emperors welcomed immigrants, extended the citizenship, and worked with slaves and freedmen. Indeed, the emperors themselves represented the openness of the Roman system to change. Augustus was a member of the nobility only on his mother's side. Many emperors came from outside Italy: from Spain, North Africa, Syria, and the Balkans, to take the main examples.

Ara Pacis Augustae

Ara Pacis Augustae - A less happy lesson is the uses of violence. The Romans acquired their empire by a combination of carrots and sticks. They were, for example, exceptionally generous in extending their citizenship. But we cannot forget the stick, that is, violence. Every Roman emperor, even a good person like Marcus Aurelius, was ready and willing to use force to maintain power. And they often abused it, as in the brutal suppression of rebellions in Britain and Judea, among other places. The Roman example makes us think about where and when a large state can or must use force.

- There is no substitute for greatness. Let us face it: most of Rome's emperors were rather forgettable. But a few of them rose to the challenge of an exceptionally difficult job. How men from such diverse backgrounds as Augustus, Hadrian, Septimius Severus, and Diocletian, for example, were all able to succeed is food for thought. The best education for leaders is a perennial question, and the Romans provide no end of material.

JBW: You close Ten Caesars with an epilogue focused on the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West in 476 CE, and its survival and transformation into the Byzantine Empire in the East. You also briefly examine the lives of Justinian (r. 527-565 CE) and Theodora (r. 527-548 CE).

Why are they are nice “bookend” to a title of imperial Roman history? In which ways do they resemble their ancient predecessors and yet still anticipate a more “medieval” style of statesmanship?

BS: Like their ancient predecessors, Justinian and Theodora were a tough and ruthless couple who provided mutual support in the pursuit of power. They were the equal of Augustus and Livia or Septimius Severus and Julia Domna. They insisted on getting at least a foothold in the old imperial heartland in Italy. The prominence of horse races in the Constantinople of their era, for better or worse, is reminiscent of imperial Rome.

Yet the hieratic style of the Ravenna mosaics, which portrays an orderly organization of both church and state around Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora, seems to look forward more to the age of faith than it does to the world of the philosophers. There is something static both about the worldview of those mosaics and the interior space of Hagia Sophia that also recalls medieval notions of order more than imperial Roman ones. So, yes, Justinian and Theodora are indeed a Janus-like pair, who look in two directions.

JBW: I thank you so much for speaking with me on behalf of Ancient History Encyclopedia! Per usual, I wish you many exciting adventures in research.

BS: Thanks, James!

Dr. Barry S. Strauss is a classicist and a military and naval historian and consultant. As the series editor of the Princeton History of the Ancient World, Professor Strauss is a recognized authority on the subject of leadership and the lessons that can be learned from the experiences of the greatest political and military leaders of the ancient world (Caesar, Hannibal, Alexander among many others). He is the author of eight books on ancient history, including Ten Caesars, The Death of Caesar (2016), The Battle of Salamis (named one of the Best Books of 2004 by the Washington Post), and The Trojan War: A New History (2006). Writing in the Washington Post, Tom Holland hailed his The Spartacus War (2009) for having “all the excitement of a thriller.” Books & Culture named it one of its favorite books of 2009. His books have been translated into 14 foreign languages, from French to Korean. Professor Strauss holds a BA from Cornell University and an MA and Ph.D. from Yale University.