In the aftermath of the failure of the Second Crusade (1147-1149 CE), which only managed to bring Damascus under Nur ad-Din's (sometimes also given as Nur al-Din, l. 1118-1174 CE) dominion, Egypt acquired top priority – both from a strategic and economic point of view, for the Crusaders and the Zengids (Oghuz Turkic rulers of regions in Syria and Iraq). Both parties made multiple attempts between 1163 CE and 1169 CE to take the kingdom which was then ruled by the Fatimids, who were inclined towards neither side as they considered both Christian Crusaders and Sunni Zengids as their rivals. In the end, the Zengids prevailed as the Crusaders posed an imminent and dire threat to the Fatimids who appealed for the former's help.

The conquest of Egypt in 1169 CE by Syrian forces under Asad ad Din Shirkuh (d. 1169 CE) and his nephew Saladin (l. 1137-1193 CE) was a turning point in the Middle East Crusades (1095-1291 CE), for it allowed the Muslims to envelop the Crusader states and pose a threat from two fronts: Syria, directly under Nur ad-Din; and Egypt, Nur ad-Din's vassal state (although this was to change soon enough). The event also holds special importance in Saladin's rise to power, as his uncle died shortly after assuming control of the newly conquered state and he would succeed him as the de facto ruler of the Kingdom of Nile – from where he would eventually found the Ayyubid Dynasty and start his own holy war or Jihad, against the Crusaders, culminating in the Battle of Hattin (1187 CE).

Egypt under the Fatimids

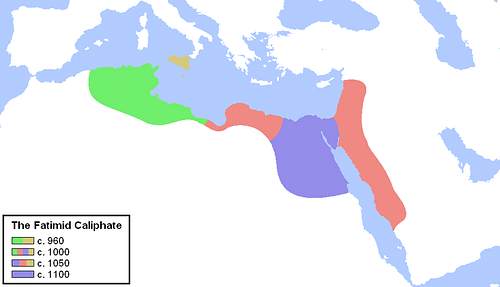

The Fatimids (909-1171 CE) were an Arabic dynasty, which at their peak ruled over vast stretches from North Africa to the Hejaz, Levant, and parts of Syria, they also held onto Sicily from 909 CE to 965 CE. They claimed to be the descendants of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad through his daughter Fatima (hence the term Fatimid) and served as a rival (anti-)Caliphate to the Abbasids. They were driven by a radical version of Shi'ism called Ismailism (Ismaili / Sevener Shia) and held different views as that of the modern and moderate Twelver Shias. Although initially spanning over a vast area, they had been reduced to Egypt by the time of the First Crusade (1095-1099 CE).

Their attempts to fight off the Crusaders from Jerusalem and Ascalon (the gateway to Egypt) had ended in crushing and humiliating defeats in 1099 CE and 1153 CE respectively. This had brought both crucial territories under Crusader occupation. From Ascalon, a full-scale Crusader invasion into Egypt was only a matter of time, and since the Fatimids were in no state of repelling it, they had been forced to offer tribute to the King of Jerusalem.

Though loaded with riches, the internal state of Egypt was no different from its failures in the field. Although the Fatimids were themselves Shias, the majority of the Muslim population of their realm was Sunni, in fact, they were a minority subgroup (perhaps even less in number than Jews) ruling over a sea of alien factions. Alexandria, the most important port city under their dominion, was the hub of opposition against their policies, and it was there that the Sunni fervor against their Shia overlords (who were growing weaker and weaker as time passed) was gaining momentum.

After the death of the eleventh Fatimid caliph, Al Hafiz (r. 1132-1149 CE), a series of child caliphs were coronated of which the last was Al Adid (r. 1160-1171 CE), who ascended the throne at the age of nine. The caliphs, hence, possessed no real authority of their own; instead, all power rested in the hands of the vizier (in modern terms a prime minister). It was during Al Adid's tenure that the court chamberlain Dirgham (d. 1164 CE) refused to continue to pay tribute to the Crusaders; he ousted the vizier Shawar (d. 1169 CE) and assumed the office for himself.

The Motives of the Zengids & the Crusaders

Nur ad-Din Zengi, the ruler of Aleppo (r. 1146-1174 CE), which he inherited from his father in 1146 CE, and Damascus (r. 1156-1174 CE), which entered his dominion after a failed attempt of the knights of the Second Crusade to besiege it, sought to drive out the Crusaders from the Holy Land just as his father had. But he was quite a different ruler from his father. Imad ad-Din, Nur ad-Din's father, considered jihad his moral duty, but he was not very pious, he drank alcohol and enjoyed the pain of others - both of these are haram or unlawful in Islam. Nur ad-Din, on the other hand, was a pious and God-fearing man; he never abused his power, nor did he spend money for himself from the state treasury (on one occasion, he even refused to give his wife some extra money to buy new clothes from the treasury). In the words of William of Tyre, he valued “justice next to godliness”, but he would not give people second chances. (When he retook Edessa, he put all Eastern Orthodox Christians, who had betrayed him by allying themselves with the Crusaders, to death.)

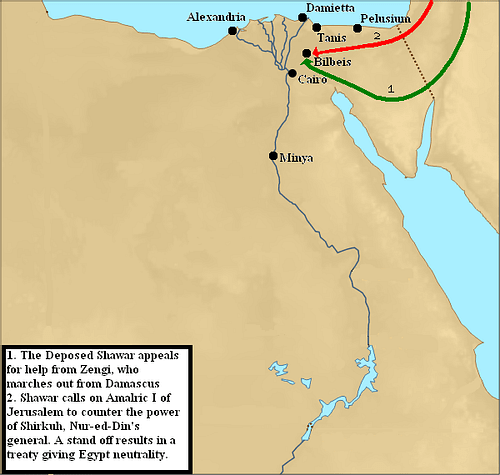

His kingdom threatened the eastern portions of the Outremer, but the western part was safe as the Fatimids were rivals of the Sunni Zengids, being Shias themselves. Since his worst rival – Damascus had been dealt with, Nur ad-Din set his eyes on Egypt, for he wished to envelop the Crusader states from both sides in a fatal pincer move. So when in 1163 CE, the deposed Shawar sought out Nur ad-Din's help for reinstating him as the vizier in Egypt, the latter, despite some initial hesitation, was only too happy to oblige. Moreover, Shawar had promised to pay for all the expenditures of the campaign and to offer one-third of the state revenue to the Zengids as an annual tribute.

There was also another, more desperate reason behind Nur ad-Din's decision to invade Egypt, one that is mostly ignored (as pointed out by historian A. R. Azzam): the survival of Islam depended on it. Hejaz, the heartland of Islam, which hosts the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina, depended heavily on Egypt for trade and support through the Red Sea. If Egypt were to fall to the Crusaders, Hejaz would be vulnerable to a Crusader invasion, which if successful would have brought an end to Islam itself.

The Crusader King of Jerusalem, Amalric I (r. 1163-1174 CE) also realized the imminent threat of a Zengid invasion of Egypt, he made multiple attempts to take over the Kingdom of the Nile between 1163 CE and 1169 CE. Amalric was a strong-willed military leader and an able king; although he stammered in his speech, his vision was crystal clear: he realized that the only hope for the Crusaders to maintain their existence was the wealth of Egypt, which would be able to finance military expeditions against the Zengids and other Muslim forces in the area. His desperation has been confirmed by multiple historians who point out that the Crusaders were constantly requesting financial aid from Europe (one can imagine that many of these requests must have been ignored considering the internal unrest in Europe itself), hence money was indeed imperative not only for their further expansion but also for their mere survival.

Unfortunately for him, Nur ad-Din felt the same way and was not going to let him take this ultimate price (ironically he would not technically be taking it for himself either). The outcome of the holy war hung in the balance on either side: neither Jihad nor Crusade could emerge victorious if the other received the backing of the lucrative trade and fertility of Egypt – war was inevitable.

The First Crusader Invasion & Nur ad-Din's Intervention

In 1163 CE, a quarrel ensued between the new vizier Dirgham and Amalric regarding the annual tribute that the Fatimids had been paying to the kingdom, and this provoked an invasion by the latter in 1163 CE. After suffering a defeat at the hand of the Franks, Dirgham, in his hour of desperation, ordered dams to be destroyed and flooded his realm to check Amalric's advance, who retreated back to Palestine.

Nur ad-Din had now made up his mind; he sent his best general on the mission – a Kurd named Asad ad Din Shirkuh – who had loyally and ably served his father and himself and whose skills on the battlefield were beyond any doubt the best among the Zengids. Shirkuh was the uncle of Saladin; most historians debate whether or not the latter was with him on this first expedition, but considering the major role he played in the subsequent forays, it is safe to assume that he was a part of the first one as well. This itself is proof of Saladin's expertise, the 26-year-old subordinate had been well-trained in warfare by his uncle and apparently was trusted by him, more than his own sons as he had picked him over them.

Dirgham tried in vain to gain the support of the locals against Shirkuh's forces, which were advancing fast, and he even stood outside the caliph's palace for his blessings but got neither. In the end, the victors were minutes away from entering Cairo, he had been deserted by his guard forces, so he tried to escape but was thrown off his horse. The fickle-minded people of Cairo, who had once supported him against Shawar, cut off his head and presented it to his rivals. Hence Shirkuh's arrival in Cairo, with only a few handpicked men, was enough for Shawar to be made the vizier.

In 1164 CE, Shawar was back in his office but he was to act as a vassal for the Zengids, and he was not ready to fulfill the promises he had made to his allies. Shawar cleverly excluded the Syrians from the walled city of Cairo, he then tried to pay off Shirkuh and Saladin so that they would leave, but the two would not budge unless ordered by their Sultan. Sensing Shawar's treachery, Shirkuh occupied the fortified city of Bilbeys. Shawar betrayed his allies and asked Amalric for help. This decision not only tarnished his reputation in the annals of history but also led to his much-celebrated death – in the words of historian David Nicolle, “history has not been kind to Shawar” (44).

Shawar's Betrayal & the Second Crusader Invasion

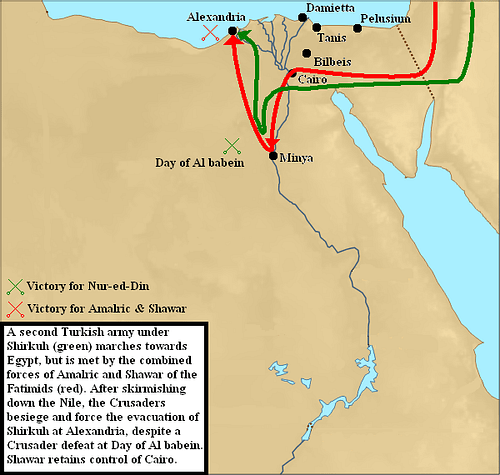

Amalric, who was eagerly preparing to attack Egypt, welcomed Shawar's appeal for help and arrived with his Crusader army; outnumbered heavily, the Syrians entrenched themselves in Bilbeys. For three months, they resisted all assaults of the combined Fatimid-Frankish force, but they were losing patience as rations fell and morale was at an ever-lowest as apparently there was no way out. In the meanwhile, news reached the Crusader camp that Nur ad-Din, who saw the absence of Amalric as an opportunity, had led a very successful assault on Palestine; he had taken Harim and was laying siege on Banias (which was going to surrender). Amalric was direly needed for the defense of his kingdom. His nobles had failed him in his absence as many of them had been taken captive.

Both sides could not continue the fight: the Syrians were at their breaking point and the Crusaders were needed back in their kingdom. A truce was signed between the two parties, the Syrians filed out of the city surrendering it to Amalric's forces. They retreated to Damascus, where they found some consolation in Nur ad-Din's gains, but Shirkuh was not content.

Shirkuh Strikes Back & the Third Crusader Invasion

Shirkuh was restless after his failure, but Nur ad-Din decided not to order another expedition for the time being. In order to convince his master, Shirkuh wrote to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad, who although possessed no authority over Nur ad-Din was nevertheless highly respected and honored for his title by the latter. The caliph sent a message, stressing that Egypt could not remain under control of those whom they considered heretics and, worse, it must not fall to Amalric. The Sultan was now obliged to act.

Shirkuh was sent once again, with around 2,000 troops under his command, to resolve the unfinished business in 1166 CE (and this time Saladin was definitely with him), he took the desert route to enter Egypt, the Gazelle Valley, to avoid detection but was instead met with a violent and devastating sandstorm. He then reached the Nile and crossed it, but in the meantime, the ever-vigilant Amalric had learned of his enemy's movements and advanced from the East; the two armies then set camp. The Crusaders were camped near Fustat (Shawar's capital) while the Syrian camp was directly facing Giza. This friendly intervention of the Crusaders was going to cost Shawar a great deal: the Egyptians were forced into a pact with the Crusaders, according to which, not only were they to act as their vassals but they were to make a huge one-time payment (200,000 gold dinars) there and then and make another similar payment in the future to the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Meanwhile, Shirkuh had requested the support of Alexandria, where the people were already resentful of their overlords for religious reasons, and seeing that they had allied with the Franks, their resentment grew into open rebellion when Shirkuh's message was received.

The Syrians faced off against the combined forces of Egyptians and Crusaders at the Battle of Al Babayn (1167 CE). The Syrians were outnumbered, but Shirkuh, a military genius, had devised a brilliant plan: Saladin was given the command of the center unit while he was himself stationed on the right. The center charged at the enemy, fought hard, and then retreated – the Crusaders chased to kill off their cowardly foes – but it was a ruse. This feigned retreat had sucked in the Crusader charge allowing Shirkuh to deliver a devastating attack from the right. Now the combined Fatimid-Frankish army was on the run for real. After the hard-earned but indecisive victory, Shirkuh did not have enough men to chase the Crusaders; instead, he took the smaller risk and turned north towards the coastal city of Alexandria, which had rebelled against the Fatimids and was only too eager to welcome the Syrian army.

Shirkuh knew that Amalric, a relentless and resilient warrior, would muster up his forces and strike back, so he took half of his men and began raiding towns in order to draw the Crusaders away from Alexandria. Saladin was left in charge as the governor; the safety of Alexandria was to be determined by his leadership and courage. It was only due to these attributes that Saladin managed to hold off the Crusader attacks and prevented its citizens from surrendering until news reached that Shirkuh was besieging Cairo. Amalric was quick to suggest another treaty stating that Egypt should be left to the Egyptians. Both forces agreed and retreated, but Amalric left some of his army (Knights Hospitaller) back in Egypt, hinting that the treaty was to be broken soon. It was a victory for Shawar who retained both Alexandria and Cairo, but not for long. The Syrians failed yet again, their allies in Alexandria paid the price for rebellion (some important leaders were executed while others were saved upon Saladin's protest to Amalric, who stopped Shawar; an act of generosity which probably had a profound effect on Saladin as well), but for Shirkuh this was not the end.

The Fourth Crusader Invasion & Shirkuh's Victory

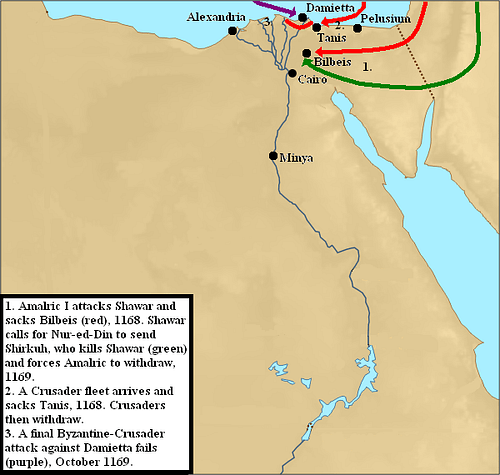

The tide suddenly changed in 1168 CE, when Amalric, encouraged the Knights Hospitaller who had bankrupted themselves over Egypt (and wished to regain the money they had lost through plunder), betrayed Shawar by attacking Bilbeys and massacring the local population; not a single soul was spared. A shocked Shawar realized that his capital – Fustat (near Cairo), would be next and since it had no walls, he ordered it to be burned down to the ground to prevent it from being used by Amalric. Although modern historians claim that this may well be an exaggeration - as mentioned earlier, no one liked Shawar - nevertheless, he retreated to the walled city of Cairo, which came under siege shortly afterwards.

Al Adid, who had been a pawn played off by Shawar until then, decided to act to save his realm: he sent a letter to Nur ad-Din begging for his help with a lock of his wife's hair to show his desperation. When he was confronted by Shawar for doing so, the young sovereign's response was immaculate, as reported by historian A. R. Azzam in his book Saladin: "As long as Egypt remains Muslim, I am ready to become the price of the Muslims." (70)

Nur ad-Din was quick to send Shirkuh yet again to Egypt, this time with a huge force, and yet again Saladin was to be his subordinate. Most historians (such as Stanley Lane Poole) put Saladin in a reluctant position at this stage, stating that he had lost all interest in Egypt, although historian David Nicolle disagrees stating that Jihad was his passion. Even if the earlier statement is true, or if his reluctance was because of a disagreement with his uncle (as pointed out by A. R. Azzam), he must have been convinced by his father.

When the duo entered Egypt for the third time, Amalric, who was at the time besieging Cairo, knew that direct confrontation was not an option (as he would be surrounded from both sides). The Crusaders retreated, and Shirkuh entered Cairo in 1169 CE. He was hailed as a hero. Al Adid hastily made the able general his next vizier as a reward for his help. Shawar, who acted his best to appear happy and unaffected, could not be trusted by Saladin and hence was killed by him personally (there are multiple versions of the story, but the gist is the same – he was either seized by Saladin personally or two mamluks or slave soldiers on his command) and his head was sent to Al Adid as per his request.

Saladin Becomes the Vizier

In the aftermath of the loss of Egypt, the Crusaders made another desperate attempt to seize it with the help of their allies: the Byzantines. They attempted a combined naval assault on Alexandria in 1169 CE. But it was not Shirkuh who repelled the attack, for he died just three months after assuming the office. As his elected successor, it was Saladin, the new vizier of Egypt, who secured Egypt for Islam, and he set his mind to a new goal as he himself said later, as reported by Beha ed Din in his book What Befell Sultan Yusuf (translated reprint):

When God allowed me to obtain possession of Egypt with so little trouble, I understood that He purposed to grant me the conquest of the Sahel (Palestine), for He Himself implanted the thought in my mind. (55-56)

The Fatimids had wrongly assumed that the young Sunni Kurd could easily be controlled. Quite on the contrary, Saladin began expanding his own power, and by 1171 CE, he was the sole sovereign of Egypt, which had been brought under the suzerainty of the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate (the ailing Al Adid died in peace, without knowing that his reign was over). First Nur ad-Din and then Amalric died in 1174 CE, and it was from that point that the man who vanquished the Crusader field army in 1187 CE (Battle of Hattin) would rise from a second-in-command to one of the strongest rulers of his time.