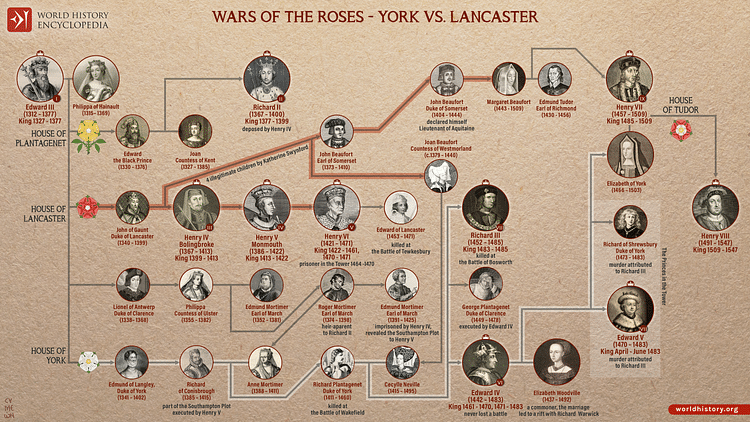

The Wars of the Roses (1455-1487 CE) was a series of dynastic conflicts between the monarchy and the nobility of England. The 'wars' were a series of intermittent, often small-scale battles, executions, murders, and failed plots as the political class of England fractured into two groups which formed around two branches of Edward III of England's descendants (r. 1327-1377 CE): the Yorks and Lancasters. Although there were several reasons why the wars continued over four decades, the main causes for the initial outbreak were the incompetent rule of Henry VI of England (r. 1422-61 & 1470-71 CE) and the ambition of Richard, Duke, of York (b. 1411 CE) and then his son Edward (b. 1442 CE). Mixed in were additional motives such as the rivalry for wealth amongst the nobility, disagreements over relations with France, the impoverished economy, the alleged crimes of Richard, Duke of Gloucester (b. 1452 CE), and finally, the ambition of Henry Tudor (b. 1457 CE) to become king.

A Rose by Any Other Name

The popular name for England's 15th-century CE dynastic conflicts, the 'War of the Roses', was first coined by the novelist Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832 CE) after the later badges of the two main families involved (neither of which were actually the favoured liveries at the time): a white rose for York and a red rose for Lancaster. The division was a little more complex than merely these two families as each one garnered allies amongst England's other noble families, thus creating two broad groups: the Lancastrians and the Yorkists. Allies of either side were also liable to switch allegiances over the course of the conflict depending on favours, deaths, and opportunities.

Neither were the wars a continuous conflict but were rather a series of battles, skirmishes, a few minor sieges, and several dynastic struggles, which continued intermittently over four decades. Indeed, so fragmented were the pieces that it is difficult to imagine the participants ever had a concept they were fighting in a coherent series of historical events we today handily label with a flower.

The precise nature of the conflict may be difficult to categorise but the competition prize was clear for all to see: the undisputed right to rule England. After the reign of the Lancaster king Henry VI of England and the Yorkist kings Edward IV of England (1461-70 & 1471-83 CE) and Richard III of England (r. 1483-85 CE), the 'wars' were finally won by the Lancastrian Henry Tudor, who became Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509 CE). Henry VII then reunited the two rival houses by marrying Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV in 1486 CE, thus creating the new house of Tudor. The mark of his success is that Henry's son Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE) became king without any wrangling and that the Tudors went on to provide the next three monarchs after him in a period of English history seen as its Golden Age.

A Summary of Causes

The multiple initial causes of the Wars of the Roses, and the reasons why they continued, may be briefly summarised as:

- the increasing tendency to murder kings and their young heirs, a strategy begun by Henry Bolingbroke in 1399 CE.

- the incapacity to rule and then illness of Henry VI of England.

- popular discontent with Henry VI's governance at a local level and the economic slump of the period.

- disagreement amongst the nobility on how to conduct the war with France.

- the phenomenon of 'bastard feudalism' where rich landowners were able to possess private armies of retainers, accumulate wealth and diminish the power of the Crown at a local level.

- in the absence of campaigns in France, nobles with private armies could gain an advantage over rivals and settle old scores in England.

- the ambition of Richard, Duke of York to become king.

- the ambition of Edward of York to avenge his father and become king.

- the ambition of Richard, Duke of Gloucester and the murder of his nephews.

- the ambition of Henry Tudor to restore the Lancastrian line of monarchs.

Might Is Right

One of the first causes of the Wars of the Roses was the precedent that stealing the throne of England by war and murder was an acceptable strategy for a future king. Henry IV of England (previously known as Henry Bolingbroke, r. 1399-1413 CE), the first Lancaster king, had done just that: usurped the throne and murdered his predecessor Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE). Kings were supposed to have been born into the role and so been chosen by God to rule. They were not supposed to steal it on the battlefield. Certainly, there had been a few dynastic hiccups along the way, but not since William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087 CE) in 1066 CE, had any king won his throne by murdering the incumbent monarch. Once this line had been crossed by Henry IV, all of his successors had to watch their backs to check the same fate did not befall them. In effect, the throne now belonged to he who had the strongest army and most baronial support.

In addition to these intrigues at the very top of the pyramid of power, the 15th century CE saw the arrival of what historians have called 'bastard feudalism'. This phenomenon, the partial degradation of medieval feudalism, allowed estate owners to call on their retainers, who sometimes numbered in the hundreds, to serve them in any capacity they saw fit, including military service. Such retainers often wore a badge, such as a boar, swan or flower, to identify themselves as the servants of a particular lord. Consequently, local barons became very powerful and their word was often law. Loyalties were thus transferred from the Crown to the local baron. In addition, these barons could become extremely rich and the king correspondingly poorer as they kept local revenues which the king could not tax without the permission of Parliament. In effect, then, the most powerful barons, whom historians have sometimes labelled 'over-mighty', were able to take over many of the functions of the royal government, further weakening both the role and power of the king. Some barons might even consider themselves worthy of becoming the next king and they could achieve this ambition by forming an alliance of like-minded barons keen to follow someone with a trace of royal blood in their veins. In short, for ambitious and ruthless men, the window of opportunity was wide open in 15th-century CE England.

The Weakness of Henry VI

Another early problem that we may trace the Wars of the Roses' origins to, is the early death of Henry V of England (r. 1413-1422 CE). When Henry died of illness in 1422 CE, he left his son as heir but the young Henry VI was not even one year old. This meant a ruling council governed England and two regents, appointed by Henry V, ruled England and the Crown's French territories respectively: Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (l. 1390-1447 CE) and John, Duke of Bedford (l. 1389-1435 CE). Both were uncles of the infant King Henry, and a third important figure in this period was Henry's great-uncle, Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester. Such a situation of divided power was ripe for exploitation by any baron eager to promote his own position at the expense of any rivals.

The king, even when he reached adulthood, proved eager to please but was easily swayed by whoever caught his ear. Henry unwisely involved himself in disputes between nobles, and this only further polarised loyalties. In addition, the English barons disagreed over the policy in France as the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453 CE) reached its closing stages. Some favoured the direct approach Henry V had taken in meeting the French in big set-piece battles, others baulked at the vast expense of such a strategy, while still others wanted a complete withdrawal. Another consequence of the lack of military activity in France was that English barons could use their private armies - often drawn from militia on their estates - to pursue their own interests at home instead of the Crown's abroad.

In 1445 CE, the marriage of Henry to Margaret of Anjou (d. 1482 CE), niece of Charles VII was yet another cause of discontent. Some war-hungry barons thought this a capitulation while others lamented the lack of a lasting peace from the union. Queen Margaret was thought to have an undue influence on the king, and Henry seemed totally uninterested in warfare. The king further alienated some barons by his support of unpopular figures at court, notably William de la Pole, the Earl of Suffolk. The rebellion of 1450 CE led by Jack Cade only brought further attention to Henry's misrule at both home and abroad as commoners protested at high taxes, perceived corruption at court, an absence of justice at local level, and the economic slump which saw a reduction in trade because of the Hundred Years' War with France. The commoners might not have had any direct influence on government but the discord did perhaps give those nobles keen to overthrow the regime another excuse to do so beyond merely extending their own interests.

When Henry VI of England had his first episode of insanity in 1453 CE those powerful barons around him saw an opportunity to improve their own position at court, perhaps even take the throne itself. Henry's illness may have been inherited from his maternal grandfather, Charles VI of France (r. 1422-1461 CE), and the factor which tipped Henry's mind over the edge might have been the loss of the Hundred Years' War. The result of this debacle was that the English Crown had lost all its territory in France except Calais. Henry became so ill that he could not move, speak or recognise anyone. In this situation, the kingdom needed a regent and, in 1454 CE, the man chosen was Richard, Duke of York, then perhaps the most powerful and talented of the English barons.

The Great Pretender: Richard, Duke of York

Richard, the Duke of York was now the Protector of the Realm but he wanted more. The duke wanted to be nominated as Henry VI's heir (at the time he had no children). Richard did have some pedigree as he was the great-grandson of Edward III of England and the nephew of the Earl of March who himself had claimed he was the legitimate heir to Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE). Richard was also seen by some as a representative of reform, a man who could sort out the corrupt government of Henry VI and restore England's waning economic and military fortunes. Richard, too, had the support of such powerful families as the Nevilles of Middleham who sought allies in their own struggles with the Percy family and others.

The problem was that Henry's wife, Queen Margaret, hated Richard and there was a rival candidate, also keen to be the next king. This was the Earl of Somerset who was also a descendant of Edward III but through that king's son John of Gaunt, father of Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413 CE), first ruler of the House of Lancaster. These two men would become great rivals, and their battle at St. Albans on 22 May 1455 CE, which Richard won, was the first of the Wars of the Roses.

When Richard, Duke of York died at the Battle of Wakefield on 30 December 1460 CE against an army loyal to Henry VI, it seemed the Wars of the Roses would end there. However, Edward, the Duke of York's son, backed by the powerful and immensely rich Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (1428-71 CE), was promoted as a replacement to his father and to King Henry. When Edward won the bloody Battle of Towton in March 1461 CE, the largest and longest battle in English history, this is indeed what transpired. Henry VI was deposed while Edward of York became Edward IV, the first Yorkist king.

Musical Thrones: Edward IV

Edward IV's reign was briefly interrupted when his old ally the Earl of Warwick turned against him and, justifying his reputation as 'the kingmaker', reinstated Henry VI in 1470 CE. Edward won back his throne on the battlefield the next year and murdered Henry in the Tower of London. The Earl of Warwick and Henry VI's only son were killed in battle, and Queen Margaret was imprisoned. It seemed the Yorkists had won the Wars of the Roses, and Edward consolidated his victory by purging any remaining powerful Lancastrians and anyone else who had been disloyal. The king, believing him guilty of treason, even murdered his own brother, George, Duke of Clarence (l. 1449-1478 CE). Edward's reign was largely peaceful, and the much-needed stability and absence of expensive campaigns in France meant the economy recovered, too.

Richard III: Murder Most Horrid

Richard, Duke of Gloucester (b. 1452 CE) was the younger brother of Edward IV. Richard had helped his brother in several significant battles against the Lancastrians but he, like his namesake father, was ambitious for the biggest prize of all. Richard was not convinced that peace with France was the best policy and may have disagreed with Edward over his treatment of George, Duke of Clarence. Another reason for the division in the Yorkist camp was Edward's wife, Elizabeth Woodville (l. c. 1437-1492 CE) who was seen as scheming against George and guilty of favouring her own relatives above all others.

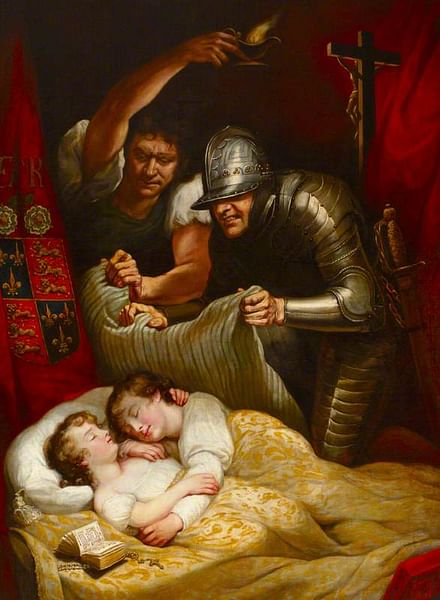

Richard's opportunity came when Edward died unexpectedly, perhaps of a stroke, in 1483 CE. The king was succeeded by his son Edward (b. 1470 CE), but he was only 12 years old. Yet again, the barons hovered around a juvenile monarch, jostling for supremacy. The young Edward V of England would only reign from April to June, and he never even had time to have a coronation. Edward and his younger brother Richard (b. 1473 CE) were imprisoned in the Tower of London where they became known as the 'Princes in the Tower'. It was not Lancastrian conspiracists who put them there, though, but their own uncle, the Duke of Gloucester. Richard had been nominated by Edward IV as the Protector of the Realm, but when the two princes disappeared, it was widely thought that Richard had murdered them - a general accusation adopted by later Tudor historians and William Shakespeare (1564-1616 CE). In 1483 CE the Duke made himself king, Richard III, but to take the throne via such a terrible crime was only asking for trouble as even pro-Yorkists were alarmed at the act. The Lancastrians, now led by Henry Tudor, were severely weakened but still a threat, and they saw their chance to grab back the crown.

The Roses Unite: Henry Tudor

Henry Tudor did have some royal blood in his veins via the illegitimate Beaufort line which descended from John of Gaunt, a son of Edward III (r. 1327-1377 CE). This was not much of a royal connection, despite the legitimisation of the Beaufort line in 1407 CE, but it was the best the Lancastrians could hope for after Henry VI had left no surviving heir. Henry Tudor allied himself with the alienated Woodvilles, such powerful lords as the Duke of Buckingham who were not happy with Richard's distribution of estates, and anyone else keen to see the king receive his just deserts. Another important ally was the new king across the Channel, Charles VIII of France (r. 1483-1498 CE).

1484 CE then saw the death of Edward, Richard III's son and heir, and once more the Lancastrians saw a glimmer of opportunity. In August 1485 CE Henry Tudor landed with an army of French mercenaries at Milford Haven in South Wales and marched to face Richard's army at Bosworth Field in Leicestershire on 22 August 1485 CE. Richard was deserted by some of his key allies, and the king was killed when he made a rash charge at Henry Tudor himself. The new king was crowned Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509 CE) on 30 October 1485 CE, and although there would still be a few minor challenges, the Tudor dynasty went on to rule England uninterrupted until 1603 CE.