The Black Death of 1347-1352 CE is the most infamous plague outbreak of the medieval world, unprecedented and unequaled until the 1918-1919 CE flu pandemic in the modern age. The cause of the plague was unknown and, in accordance with the general understanding of the Middle Ages, was attributed to supernatural forces and, primarily, the will or wrath of God.

Accordingly, people reacted with hopeful cures and responses based on religious belief, folklore and superstition, and medical knowledge, all of which were informed by Catholic Christianity in the West and Islam in the Near East. These responses took many forms but, overall, did nothing to stop the spread of the disease or save those who had been infected. The recorded responses to the outbreak come from Christian and Muslim writers primarily since many works by European Jews – and many of the people themselves – were burned by Christians who blamed them for the plague and among these works, may have been treatises on the plague.

No matter how many Jews, or others, were killed, however, the plague raged on and God seemed deaf to the prayers and supplications of believers. In Europe, the perceived failure of God to answer these prayers contributed to the decline of the medieval Church's power and the eventual splintering of a unified Christian worldview during the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648 CE). In the East, Islam remained intact, more or less, owing to its insistence on the plague as a gift which bestowed martyrdom on the victims and transported them instantly to paradise as well as the view of the disease as simply another trial to endure such as famine or flood.

Although many of the religious ideas concerning the plague in West and East were similar, this one difference was significant in maintaining Islamic cohesion, even though it most likely led to a higher death toll than official records maintain. After the plague had run its course, religious response in both East and West was generally credited with appeasing God who lifted the pestilence but Europe would be radically changed while the Near East was not.

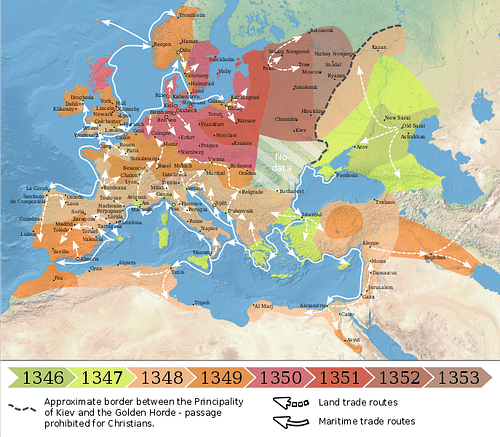

The Black Death Origin & Spread

The plague originated in Central Asia and spread via the Silk Road and troop movements throughout the Near East. The first recorded outbreak of bubonic plague is the Plague of Justinian (541-542 CE) which struck Constantinople in 541 CE and killed an estimated 50 million people. This outbreak, however, was simply the furthest westerly occurrence of a disease that had been stalking the people of the Near East for years before. The historian John of Ephesus (l. c. 507 - c. 588 CE), an eyewitness to the plague, notes that the people of Constantinople were aware of the plague for two years before it came to the city but made no provision against it, believing it was not their problem.

After Constantinople, the plague died down in the East only to appear again with the Djazirah Outbreak of 562 CE which killed 30,000 people in the city of Amida and even more when it returned in 599-600 CE. The disease maintained this pattern in the East, seeming to disappear only to rise again, until it picked up momentum beginning in 1218 CE, further in 1322 CE, and was raging by 1346 CE.

It was around this time that the Mongol Khan Djanibek (r. 1342-1357 CE) was laying siege to the port city of Caffa (modern-day Feodosia in Crimea) which was held by the Italians of Genoa. As his troops died of plague, Djanibek ordered their corpses catapulted over Caffa's walls, thereby spreading the disease to the defenders. The Genoese fled the city by ship and so brought the plague to Europe. From ports such as Marseilles and Valencia, it spread from city to city with every person who had had contact with anyone from the ships and there seemed no way to stop it.

Christian vs. Muslim View of Plague

Responses to the plague were informed by the dominant religions of West and East as well as the traditions and superstitions of the regions and presented as a narrative which explained the disease. Scholar Norman F. Cantor comments:

The scientific method had not yet been invented. When faced with a problem, people in the Middle Ages found the solution through diachronic (as opposed to synchronic) analysis. The diachronic is the historical narrative, horizontally developing through time: “Tell me a story”. With their fervent historical imagination, medieval people were very good at giving diachronic explanations for the outbreak of bubonic plague. (17)

Reactions, then, were based on the religious narratives created to explain the disease and fall, generally, into three beliefs about the plague held, respectively, by medieval Christianity and Islam. Even empirical observation was informed by religious belief, as in the case of whether the plague was contagious.

Christian View:

- The plague was a punishment from God for humanity's sins but could also be caused by “bad air”, witchcraft and sorcery, and individual life choices including one's piety or lack of it.

- Christians – especially in the early period of the outbreak – could leave a plague-stricken region for one with better air which was not infected.

- The plague was contagious and could be passed between people but one could protect oneself through prayer, penitence, charms, and amulets.

Muslim View:

- The plague was a merciful gift from God which provided martyrdom for the faithful whose souls were instantly transported to paradise.

- Muslims should not enter nor should they flee from plague-stricken regions but should remain in place.

- The plague was not contagious because it came directly from God to specific individuals according to God's will.

Again, these are general views held by the majority and not every cleric of Europe or the Near East agreed with them nor did every layperson. These beliefs, however, carried enough weight with believers to encourage responses which – again, generally – fall into five main reactions.

Christian Response:

- Penitential processions, attending mass, fasting, prayer, use of amulets and charms

- The Flagellant Movement

- Supposed cures and fumigation of “bad air”

- Flight from infected areas

- Persecution of marginalized communities, especially the Jews

Muslim Response:

- Prayer and supplication at mosques, processions, mass funerals, orations, fasting

- Increased belief in supernatural visions, signs, and wonders

- Magic, amulets, and charms used as cures

- Flight from infected areas

- No persecution of marginalized communities, respect for Jewish physicians

Christian Response in Detail

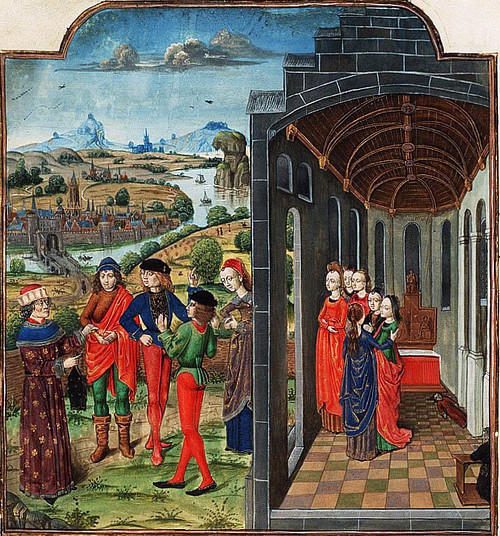

Since the plague was thought to have been sent by God as a punishment, the only way to end it was admission of one's personal sin and guilt, repentance of sin, and renewed dedication to God. To this end, processions would wind their way through cities from a given point – say the town square or a certain gate – to the church or a shrine, usually dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Participants would fast, pray, and purchase amulets or charms to keep them safe. Even after European Christians understood that the plague was contagious, these processions and gatherings continued because there seemed no other way to appease God's wrath.

As the plague raged and traditional religious responses failed, however, the Flagellant Movement emerged in 1348 CE in Austria (possibly Hungary also) and spread to Germany and Flanders by 1349 CE. The flagellants were a group of zealous Christians, led by a Master, who roamed from town to city to countryside whipping themselves for their sins and the sins of humanity, falling to the ground in penitential frenzy, and leading communities in the persecution and slaughter of Jews, gypsies, and other minority groups until they were banned by Pope Clement VI (l. 1291-1352 CE) as ineffectual, disruptive, and upsetting.

Cures were also often based on religious understanding, such as killing and chopping up a snake (associated with Satan) and rubbing the pieces on one's body in the belief that the “evil” of the disease would be drawn to the “evil” of the dead serpent. Drinking a potion made of unicorn horn was also considered effective as the unicorn was associated with Christ and purity.

Bad air, which was thought to be the result of planetary alignment or supernatural forces (usually demonic) was driven out of homes by incense or burning thatch and by carrying flowers or sweet-smelling herbs on one's person (a practice referenced in the children's rhyme “Ring Around the Rosie”). One could also fumigate one's self by sitting near a hot fire or a pond, pool, or pit used for dumping sewage as it was thought the “bad air” in one's body would be drawn to the bad air of the sewage.

People in the cities, almost always the wealthy upper class, fled to their villas in the countryside while poorer people and farmers often left their lands in rural areas for the city where they hoped to find better medical care and available food. Even after the plague was understood to be contagious, people still left quarantined cities or regions and spread the disease further.

Persecutions of Jews by the Christian community did not start with the Black Death or end there but certainly increased in Europe between 1347-1352 CE. Scholar Samuel Cohn, jr. notes:

That the blind fury of mobs comprised of workers, artisans, and peasants was responsible for the Black Death annihilation of Jews derives from modern historians' musings, not the medieval sources. (5)

Even so, he concedes, “the Black Death unleashed hatred, blame, and violence on a more horrific scale than by any pandemic or epidemic in world history” (6). Although his claim regarding modern historians' interpretation of pogroms against Jews has some validity, it does not seem to fully take into consideration the long-standing animosity felt toward Jews by Christian communities. Jews were routinely suspected of poisoning wells, murdering Christian children in secret rites, and practicing various forms of magic in order to injure or kill Christians. Scholar Joshua Trachtenberg cites one example:

[The townspeople], petitioning for the expulsion of the Jews, affirmed that their danger to the community extended far beyond an occasional child murder, for they dry the blood they thus secure, grind it to a powder, and scatter it in the fields early in the morning when there is a heavy dew on the ground; then in three or four weeks a plague descends on men and cattle, within a radius of half a mile, so that Christians suffer severely while the sly Jews remain safely indoors. (144)

In 1348 CE, Jews in Languedoc and Catalonia were massacred and, in Savoy, were arrested on charges of poisoning the wells. In 1349 CE, Jews were burned en masse in Germany and France, but also elsewhere in spite of papal bulls issued by Pope Clement VI expressly forbidding these types of actions.

Muslim Response in Detail

Muslims also gathered in large groups at mosques for prayer, but these were prayers of supplication, requesting God lift the plague, not penitential prayers for the forgiveness of sins. Scholar Michael W. Dols notes that “there is no doctrine of original sin and man's insuperable guilt in Islamic theology” (10) and so religious responses to the plague took the same form as supplications for a good harvest, a healthy birth, or success in business. Dols writes:

An important part of [Muslim] urban activity in response to the Black Death was the communal prayers for the lifting of the disease. During the greatest severity of the pandemic, orders were given in Cairo to assemble in the mosques and to recite the recommended prayers in common. Fasting and processions took place in the cities during the Black Death and later plague epidemics; the supplicatory processions followed the traditional form of prayer for rain. (12)

Mass funerals were conducted along the lines of traditional burial rites with the addition of an orator who would request the plague be lifted but, again, there was no mention of the sins of the deceased nor any reason given why they died and another lived; these things happened according to the will of Allah.

Belief in supernatural visions and signs markedly increased. Dols cites the example of a man from Asia Minor who came to Damascus to inform a cleric of a vision he had been granted of the prophet Muhammad. In the vision, the prophet told the man to have the people recite the surah of Noah from the Quran 3,363 times while asking God to relieve them of the plague. The cleric announced the vision to the city and the people “assembled in the mosques to carry out these instructions. For a week the [people] performed this ritual, praying and slaughtering great numbers of cattle and sheep whose meat was distributed among the poor” (Dols, 11). Another man who received a vision from Muhammad claimed the prophet had given him a prayer to recite which would lift the plague; this prayer was copied and distributed to people with the instruction to recite it daily.

While the majority of Muslims believed that the plague had been sent by God, there were many who attributed it to the supernatural power of evil djinn (genies). Ancient Persian religion – pre- and post-Zoroaster (c. 1500-1000 BCE) – attributed various events and illnesses to the work of the malevolent deity Ahriman (also known as Angra Mainyu) or to spirits who sometimes advanced his agenda, such as djinn. This belief gave rise to an increase in folk magic and the use of amulets and charms to ward off evil spirits. The charm or amulet would be inscribed with one of the divine names or epithets of God and prayers and incantations would be recited to imbue the artifact with magical protective powers.

As in Europe, those who could afford to do so left infected cities for the countryside and people from rural communities came to the cities for the same reasons as their European counterparts. Since the plague was not believed to be contagious, there was no reason for one to remain in one place or another except for a proscription attributed to Muhammad who forbade people going to or fleeing from plague-stricken regions. The reason for this proscription is unknown and it seems people ignored it because, whether the plague came from Allah or a djinn, it was not within an individual's power to escape the fate God had decreed. For the faithful Muslim, the plague was a merciful release from the world of multiplicity and change to the eternal, unchanging paradise of the afterlife; it seems only to have been considered a punishment for infidels outside the faith.

Even so, there is no evidence that minority populations – whether Christians, Jews, or any other – were persecuted in the Near East during the years of the plague. Jewish physicians, in fact, were highly regarded even though they could do no more for plague victims than any others.

Conclusion

As the plague raged on, people in Europe and the Near East continued their religious devotions which, after it had passed, were credited with finally working to influence God to lift the plague and restore a sense of normalcy to the world. Even so, the seeming ineffectuality of the Christian response to the people of the time caused many to question the vision and message of the Church and seek a different understanding of the Christian message and walk of faith. This impetus would eventually contribute to the Protestant Reformation and the change in philosophical paradigm which epitomizes the Renaissance.

Scholar Anna Louise DesOrmeaux notes that a significant aspect of the change in the religious model was the Christian belief that God had caused the plague to punish people for their sins and so there was nothing one could do but “turn humbly to God, who never denies His aid” (14). And yet, to the people of the time, it seemed as though God had denied his aid and this led people to question the authority of the Church.

No such dramatic change occurred in the Near East, however, and Islam continued on after the plague with little difference in understanding and observance than before. Dols comments:

The comparison of Christian and Muslim societies during the Black Death points to the significant disparity in their general communal responses…the Arabic sources do not attest to the “striking manifestations of abnormal collective psychology, of dissociation of the group mind,” which occurred in Christian Europe. Fear and trepidation of the Black Death in Europe activated what Professor Trevor-Roper has called, in a different context, a European “stereotype of fear”…Why are the corresponding phenomena not found in the Muslim reaction to the Black Death? The stereotypes did not exist. There is no evidence for the appearance of messianic movements in Muslim society at this time which might have associated the Black Death with an apocalypse. (20)

A number of Christian European writers of the time, and afterwards, refer to the Black Death as “the end of the world” while Muslim scribes tend to focus on the death toll in emphasizing the magnitude of the pestilence; they do so, however, in the same way they write about deaths from floods or other natural disasters. In the aftermath of the Black Death, Europe would be radically transformed in social, political, religious, philosophical, medical, and many other areas while the Near East would not; because of a different interpretation of exactly the same phenomenon.