The Battle of Marj Ayyun (10 June 1179, also given as the Battle on the Litani) was a military engagement between Baldwin IV, King of Jerusalem (r. 1174-1185) and Saladin, Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193). Saladin decisively won the battle, enabling his victory at the Siege of Jacob's Ford in August 1179.

Saladin had been badly beaten by Baldwin IV at the Battle of Montgisard in November 1177, weakening his reputation as a military leader. Baldwin IV, meanwhile, had strengthened his position by fortifying castles and commissioning the construction of a new citadel at Jacob's Ford, the most secure crossing over the Jordan River between its point of origin and the Sea of Galilee, making it a strategically important site not only for Baldwin IV and Saladin but also for the various factions on both sides vying for control in the region as well as for trade.

In June 1179, Saladin was on reconnaissance in planning his attack on Jerusalem when his nephew, Faruk-Shah, encountered Baldwin IV's army near the Litani River by the town of Marj Ayyun (modern-day Marjayoun, Lebanon). Baldwin IV was accompanied by Raymond III, Count of Tripoli (r. 1152-1187) and Odo of St. Amand, Grand Master of the Knights Templar (served 1171-1179). Odo engaged the forces of Faruk-Shah's raiding party, unaware of Saladin's larger cavalry force which fell upon him, driving his forces in a rout back upon the troops of Baldwin IV and Raymond III, who narrowly escaped capture.

Odo of St. Amand was taken along with a significant number of knights, while Baldwin IV and Raymond III retreated to the safety of nearby Beaufort Castle and then further to Tiberias, roughly 14 miles (23 km) to the south. Saladin's victory at Marj Ayyun enabled him to move his troops to Jacob's Ford, which fell after a short siege. Although Saladin would lose the next two engagements to Baldwin, Marj Ayyun and Jacob's Ford restored the prestige he had lost after Montgisard, allowing him to consolidate a larger army for his 1187 victories at the Battle of Cresson and the Battle of Hattin, which led directly to the fall of Jerusalem on 2 October 1187.

Background

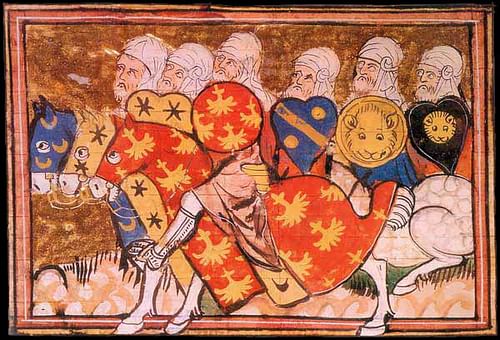

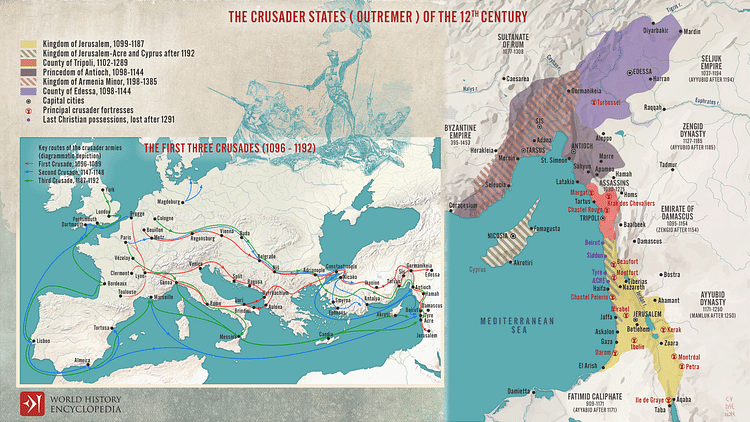

After the First Crusade (1095-1102), the four Crusader States were established along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea from roughly the sites of modern-day Syria down to Israel: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. These were created by the European crusaders to maintain their control of the Holy Land won in the First Crusade. Scholar J. F. C. Fuller notes:

The crusaders never conquered the land, all they did was to occupy parts of it, which on one flank were supplied by the sea, and on the other protected by a chain of magnificent castles. (412)

The Crusader States were supplied and periodically fortified by European ships, enabling them to maintain a strong political and military presence in the Near East. The most important of these was the Kingdom of Jerusalem, whose famous city was central to the religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The First Crusade was launched to take Jerusalem from the Muslims and fell to the crusaders in 1099. It was a highly symbolic victory, which Saladin, once he came to power, was anxious to reverse.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was not restricted to the one city and its immediate surroundings but controlled the economically vital region of the Levant, including Acre, Caesarea, Nablus, Sidon, and Tyre. It was under the control of the Franks, as were the other Crusader States, and all were aided in their defense by the military/religious orders of the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights Templar, highly trained and disciplined warriors who often controlled their own castles and fiefdoms.

The Hospitallers and Templars did not always share the interests of each other, nor those of the kings of the principalities who were engaged in their own power struggles from the very beginning. Alliances among the Europeans were made and quickly broken, just as they were among the tribes and cities of their opponents. Scholar John Man describes the territorial/political situation of the area in the 12th century:

The whole region was seething. Imagine it as a nightmarish snooker table, with iron balls that are magnets of different strengths and sizes. If you listed them all, there would be dozens. Here are some: Egypt and Syria, Syria's major cities, their rivals for leadership, the Franks in Jerusalem, the other Frankish enclaves, rogue Frankish commanders, Frankish rivals for power, Frankish marriages, Bedouin desert-dwellers, Byzantium, the Seljuk Turks of Rum, the caliph in Baghdad, Saladin's own family, and off at the far end of the table a scattering of European rulers and nobles – all these and more governed by the whim or calculation of individuals, all affecting each other by their moves, repelling, attracting, sticking together in perverse alliances, cannoning off each other in a multiplicity of effects, and sometimes vanishing forever into a side-pocket labelled 'Death' or 'Defeat'. [In 1174] Saladin was not yet the master-player. All he could do for the moment was wait, watch, and hope for an alignment that would favor him. (121)

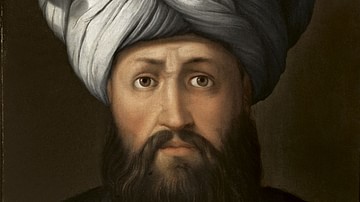

Saladin became the Sultan of Egypt in 1174 and captured Damascus that same year. He then unified the Muslim cities under his control and defeated his rivals in battle in 1175, claiming for himself the role of champion of the Islamic faith and, specifically, Sunni Muslim orthodoxy. He established a reputation for diplomatic skill, strategic brilliance, and mercy toward the defeated – which won him even greater support – and swelled the ranks of his army with recruits.

Battle of Montgisard

Baldwin IV, King of Jerusalem, had been diagnosed with leprosy at the age of nine, which normally would have disqualified him for rule, but as there was no other suitable heir to the throne, he came to power in 1174 at the age of 13 when his father, Amalric, died of dysentery. Baldwin IV had no sensation in his right arm, due to the disease, and taught himself to control a horse with only his knees and wield a sword with his left hand. In 1176, when Saladin was already an experienced warrior, Baldwin IV had only participated in a few raids.

In 1177, the visiting noble Philip of Alsace (l. 1143-1191) joined with Raymond III of Tripoli and the Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar for an attack on Saladin's positions in Syria, leaving Jerusalem largely undefended. Saladin saw his opportunity and marched toward the city at the head of an army of between 10,000-26,000 soldiers. Baldwin IV, hearing of his approach, led an army of less than 7,000 to meet him. The numbers for both sides have been challenged repeatedly, and so these should be understood as rough estimates.

Saladin entered the region of the Kingdom of Jerusalem via Jacob's Ford, the most reliable crossing of the Jordan River between his territory of Damascus and the kingdom of Baldwin IV. He did not consider Baldwin IV a threat as the king was so young and, as he had been told, commanded a fairly small force, and so allowed his army to spread out, sacking villages and foraging for food. Consequently, when Baldwin IV's army caught Saladin at Montgisard, the latter was wholly unprepared.

Baldwin IV, outnumbered, inexperienced, suffering leprosy, and only 16 years old, defeated Saladin who, according to the chronicler William of Tyre (l. 1130-1186), only escaped capture by fleeing the field on a camel. His defeat resulted in a loss of prestige, which he then needed to win back. In 1178, he defeated two crusader armies, re-establishing his reputation, and planned another expedition against the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Jacob's Ford

After his victory at Montgisard, Baldwin IV understood he needed to control Jacob's Ford to prevent another attack on his kingdom. He marched from Montgisard to the ford and commissioned the construction of a castle which would be fortified to repel any future invasion. In 1177, there was no official border between the Crusader States and the surrounding region, and so Baldwin IV decided to establish one clearly. Man writes:

A castle at Jacob's Ford would in effect create a frontier by grabbing land, policing it with a small army, and barring Saladin from following this route to Jerusalem. Baldwin took charge in person. Work started in October 1178, in a frantic race against time. Indeed, the whole short life of Jacob's Ford was frantic, from conception and creation to occupation and destruction. It would have been the largest castle of its day in the whole eastern Mediterranean, and it might have lasted for centuries. As things turned out, its life was all over in eleven months, perhaps the shortest of any castle ever. (113-114)

The castle needed to be built and fortified before Saladin could mount another invasion, but all the supplies – wood, stone, food, tools – had to be brought in by carts from the surrounding area, and this, as well as arguments over design, slowed construction. Baldwin IV, in an effort to hasten progress, approved foraging parties to take what resources could be found in the lands close at hand, apparently even leading some of these himself.

The Battle of Marj Ayyun

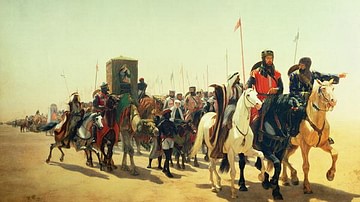

By the early summer of 1179, Saladin was prepared to strike again at Jerusalem and sent raiding parties against the agricultural communities of the Crusader States to cut their food supply. He placed his nephew, Faruk-Shah, in command of one of the parties that raided the coastal towns of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in the region of present-day Lebanon. At about this same time, Baldwin IV, Raymond III, and Odo of St. Amand were leading a large foraging party in the same area Faruk-Shah was returning through, near the small village of Marj Ayyun.

According to the account of William of Tyre (who had been a tutor and mentor to Baldwin IV when the king was young but was not present at the battle), Baldwin learned of the position of Faruk-Shah's raiding party and mobilized his army to attack. Saladin, watching for the return of his nephew from an observation post on a high hill, noticed the flocks of sheep in a far field beyond the Litani River had been stirred into a panic and were quickly scattering. Interpreting this as a sign of a force on the march far larger than Faruk-Shah's, he drew up his cavalry and advanced.

Baldwin IV's army, with Odo and his Knights Templar at the front, encountered Faruk-Shah by the Litani, and Odo ordered his men to attack. His mounted knights outdistanced the infantry and the rest of the foraging party and struck at the heart of Faruk-Shah's forces. Faruk-Shah was driven across the river with Odo in pursuit, suffering significant losses as they fled the field. Odo, confident of his victory, halted his charge and waited for the rest of the force under Baldwin IV and Raymond III to join him. Suddenly, Saladin and his cavalry appeared, bearing down on the troops of Odo and the newly arrived Raymond III, and scattering them in confusion. Scholar Steven Runciman describes the battle:

The templars joined battle at once; but Saladin's counterattack drove them back in confusion on Baldwin's troops. These, too, were forced back; and before long the whole Christian army was in flight. The King and Count Raymond were able, with part of their men, to cross the Litani and shelter at the great castle of Beaufort, high above the western bank. All the men left beyond the river were massacred or later rounded up. Some of the fugitives did not stop at Beaufort but made straight for the coast. (420)

Among Saladin's prisoners of war was Odo of St. Amand whom William of Tyre blames completely for the defeat. While it is possible that Odo acted too rashly, even William of Tyre's account seems to suggest there was no way anyone among Baldwin IV's army could have known a much larger force than the raiding party was anywhere nearby.

Siege of Jacob's Ford

Saladin's victory left Jacob's Ford, whose castle was only half-finished at the time of Marj Ayyun, with only a small force to defend it. Saladin had earlier tried to buy the castle – and so control the ford – but his offers were rejected. After Baldwin IV's defeat at Marj Ayyun, he led his troops to Tiberias – less than a day's march from Jacob's Ford – to regroup. Saladin, meanwhile, after continuing his raids on Baldwin IV's kingdom, moved his forces to Jacob's Ford and placed the citadel under siege on 23 August 1179.

When the defenders refused to surrender, Saladin ordered his sappers to tunnel up under the wall and lay mines. The first attempt failed as the tunnel stopped just short of the outer wall of stone, giving the defenders time to build a wooden stockade inside the compound in case the wall fell. On the sapper's second attempt, the mines brought the outer wall down, set fire to the stockade, and Saladin's forces took the citadel, killing most of the defenders and enslaving those who survived the attack. After the battle, Saladin ordered the castle destroyed and claimed Jacob's Ford for himself on 30 August, securing his victory and moving on before Baldwin IV had time to march on him from Tiberias.

Conclusion

In 1180, Baldwin IV and Saladin signed a truce which was broken by Raynald of Chatillon (l. c. 1125-1187) by 1183 when he attacked a Muslim pilgrimage party and engaged in a campaign of looting and pillaging Muslim villages. Baldwin IV died of his disease in 1185 and was succeeded by his brother-in-law Guy of Lusignan (l. c. 1150-1194), husband of Baldwin IV's sister Sibylla of Jerusalem (l. c. 1159-1190). In July 1187, Guy of Lusignan, Raynald of Chatillon, and Raymond III of Tripoli met Saladin at the Battle of Hattin and were decisively defeated. Guy and Raynald were captured and Raynald executed by Saladin himself. Odo of St. Amand had refused to be ransomed with the others taken at Marj Ayyun and died in prison.

After the Battle of Hattin, Saladin moved on Jerusalem whose defense was led by Balian of Ibelin (l. c. 1143-1193) whose brother, Baldwin, was among those captured with Odo at Marj Ayyun and ransomed for a high price. As with others, whose ransoms were not nearly so high, the price demanded for his safe return depleted funds which would otherwise have gone toward funding the European efforts in the Near East, allowing Saladin a much easier victory over the Crusader States.

Balian of Ibelin is best known in the present day from the 2005 film Kingdom of Heaven which presents a significantly fictionalized vision of him and the events leading up to the fall of Jerusalem. Saladin, after a failed assault, took the city through negotiation (as presented accurately in the film). Non-Muslim citizens who could afford to pay a ransom were allowed to leave; others were sold into slavery. Raymond III fled to Tripoli where he died soon after, possibly of pleurisy, and Saladin died in 1193 of natural causes after successfully fending off the European attempt at retaking Jerusalem in the Third Crusade.

One cannot say that the Battle of Marj Ayyun led directly to Saladin's conquest of Jerusalem (1187 CE) but, without that victory – which allowed for the capture of Jacob's Ford and easier access from Damascus to the Kingdom of Jerusalem – Saladin's later victories would seem much more difficult to imagine. Saladin's victory at Jacob's Ford allowed him free access to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and that was only made possible by Baldwin IV's defeat at the Battle of Marj Ayyun.