The sea dogs, as they were disparagingly called by the Spanish authorities, were privateers who, with the consent and sometimes financial support of Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE), attacked and plundered Spanish colonial settlements and treasure ships in the second half of the 16th century CE. With only a license from their queen to distinguish them from pirates, mariners like Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE) and Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552-1618 CE) made themselves and their backers immensely rich. Elizabeth and her government, unable to trade legitimately with the colonies of the New World as Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598 CE) held on to his monopoly, turned instead to robbery as a means to persuade the Spanish king to change policy. As Anglo-Spanish relations deteriorated, the privateers became a useful tool in reducing the wealth of Spain and disrupting Philip's plans to build his Armada fleet with which he hoped to invade England. Although in some respects successful, especially with such captures as the great treasure ship the Madre de Deus, the privateers did not work together sufficiently to pose a serious and sustained threat to Spanish shipping, which began to use armed convoys to great effect. For a few decades, though, the fast English ships bristling with cannons and captained by audacious adventurers, caused havoc on the High Seas.

The New World

Spain's huge empire in the Americas was a tempting source of wealth for rival European powers. The Spanish plundered gold, silver, and gemstones from the many different states they had conquered on the continent and sent these riches back to Europe on treasure ships, often in an annual fleet which was sometimes called the plate fleet (from the Spanish for silver, plata). They also had treasure ships coming from Asia - the Manilla Galleons - loaded with costly spices, fine porcelain, and other precious goods, especially when Philip II of Spain also became the king of Portugal in 1580 CE. The second attraction was the opportunity for trade both with indigenous peoples in the Americas and with Spanish colonial settlers there. As Philip wanted to keep out rival powers from this second source of wealth, so monarchs like Elizabeth I of England turned to the first as an alternative. Peaceful trade had been attempted by such mariners as John Hawkins in the 1560s CE, but the Spanish attack at San Juan D'Ulloa, the port for Vera Cruz in Mexico, which destroyed all but two of Hawkins' ships, clearly showed the Spanish would not give up their trade monopoly in the Americas to other nations even if they themselves could not meet the demand for slaves and cloth, in particular.

By plundering Philip's treasure ships and colonial settlements, England could get richer, rival Spain would get poorer, and the Spanish king might then permit free trade in the western Atlantic. To this end, Elizabeth not only turned a blind eye to acts of piracy by her subjects but actively encouraged them. This encouragement came in many different forms such as secret orders, official licenses to sail armed privateer ships (letters of marque), money to buy ships and stores, the use of royal naval ships, and recognition such as titles and estates in the case of success. The queen often invested in the joint-stock companies which were created to fund specific privateering expeditions. Some voyages also included exploration of new territories or new trade routes like the Northwest Passage that was hoped might connect North America to Asia. It is debatable, though, if Elizabeth ever really wished to create new colonies, especially when she could immediately grab resources produced by those of a rival monarch.

There was not much to lose, either. For a few thousand pounds or a few old ships, the queen could reap vast profits from those expeditions which came home with holds bulging with precious goods. Certainly, this type of economic warfare was cheaper than funding large land armies, and although what she called the 'chested treasure' might be irregular, it did lessen the tax burden on her subjects. Some years the profits from privateering even exceeded the mid-16th century CE annual income of England. Yet another advantage was that privateers gained experience at sea and kept their ships occupied with both being then available for use in a national emergency like the Spanish Armada invasion of 1588 CE. At the same time, Philip's own fleet would be made correspondingly weaker.

The Captains

Curiously, many of Elizabeth's sea dogs were from Devon and many, too, were related either by blood or marriage. The family histories and local seafaring culture must have inspired youngsters to follow in their father's wakes and captain privateering vessels. These captains were sometimes great servants of their sovereign, at other times complete liabilities, as the historian S. Brigden explains:

Out of sight of land, captains might choose to be traders, pirates or explorers, or each in turn. Who could bind them once at sea? In the tiny world of a ship, captains had monarchical, even tyrannical, powers, if they could prevent their crew from mutiny. (278)

The captains had few qualms about the risks involved in privateering or being held to account by the authorities. As Walter Raleigh once stated, "Did you ever know of any that were pirates for millions?" (Williams, 225). In other words, given the huge quantities of treasure involved, the privateers were obviously a part of a state mechanism and not common thieves.

Francis Drake

The most famous of all the sea dog captains was Sir Francis Drake who not only believed that privateering was a sound political and economic strategy but that it was also a means to wage a religious war between Protestant England and Catholic Spain. Roaming the Atlantic and Caribbean capturing their treasure ships, the Spanish called Drake 'El Draque' ('the Dragon'). Drake infamously attacked the Spanish settlement of Nombre de Dios and captured a caravan of silver in Panama in 1573 CE. Then, illustrating the crossover between exploration and privateering, Drake completed the circumnavigation of the globe between 1577 and 1580 CE.

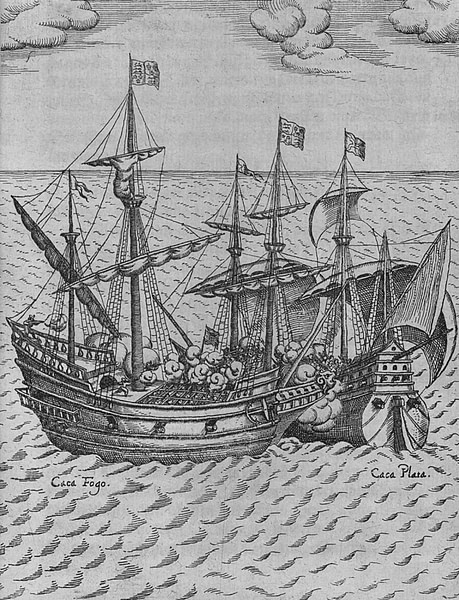

In an epic voyage in his 150-ton Golden Hind, Drake attacked ships in the Cape Verde Islands, sailed down the coast of South America, and then up into the Pacific Ocean where raids were made on Spanish colonial settlements such as Valparaiso and yet more treasure ships were looted. Charts were made of the coastlines encountered, and in March 1579 CE, the voyage's richest prize was taken off the coast of Peru, the Nuestra Senora de la Concepćion (aka Cacafuego). It took six days to empty the Cacafuego of its cargo of gold and silver.

Working his way along the coasts of Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Mexico, Drake captured yet more ships and booty. The mariner explored the possible existence of the Northwest Passage to Asia and then turned south again to arrive near what is today San Francisco, where he claimed the land for his queen, naming it 'New Albion' (a claim never subsequently pursued). The intrepid mariner then crossed the Pacific and arrived in the East Indies (Indonesia and Philippines) and took on board valuable spices. He got away with grounding his ship on a reef, crossed the Indian Ocean, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and made it back to Plymouth after a voyage of 2 years and 9 months. The estimated value of the loot taken was perhaps £600,000, that is more than double the entire annual revenue of England. Elizabeth was delighted with her favourite sea dog and knighted him on board the Golden Hind. Such formal recognition was a clear message to Philip that her sea dogs were representatives of their monarch and quite different from the pirates of all nationalities (English included) who roamed the seas. Drake had also made himself the richest man in England in terms of ready cash, an inspiration to all other privateers, and an enduring national hero. The Golden Hind was still on public display a century after its most famous voyage.

Through the 1580s CE, Drake sailed far and wide, making often audacious raids on Spanish wealth in the Cape Verde Islands, San Domingo, Cuba, Colombia, Florida, and Hispaniola (Haiti). In 1587 CE Drake illustrated the usefulness of privateers in national defence when his raid on Cadiz destroyed 31 Spanish ships, captured another six and destroyed valuable supplies destined for Philip's planned Armada.

Walter Raleigh

Raleigh was a privateer captain who was also something of a colonist. He organised three expeditions to form a colony on the coast of North America in the 1580s CE. It was hoped this could serve as a useful base to attack Spanish ships in the Caribbean. The Roanoke colony in 'Virginia' was abandoned but the expeditions were notable for introducing tobacco and the potato to England. Raleigh went on two failed expeditions to find the fabled city of gold El Dorado in South America in 1595 CE and 1617 CE. The courtier-mariner was involved in the (second) raid on Cadiz of 1596 CE which destroyed 50 Spanish ships, but he would spend most of his later years in the Tower of London after upsetting James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE). It was there he wrote his celebrated History of the World.

Raleigh's greatest contribution to Elizabeth's scrapbook of sea dog memories was his fleet's capture of the Portuguese treasure ship Madre de Deus (aka Madre de Dios), in the Azores in 1592 CE. This was the single greatest prize ever taken by Elizabeth's privateers. Raleigh funded the expedition (but was not there in person) which captured the ship which was carrying goods from the East Indies for Philip of Spain. The carrack had 32 cannons and a crew of 700 but was eventually overwhelmed by the English ships working in unison. The 500-ton cargo consisted of gold, silver, pearls, jewels, bales of fine cloth and rolls of silk, exotic animal hides, crystalware, Chinese porcelain, spices, unworked ivory and ebony, and perfumes. The queen alone received some £80,000 worth of goods, not at all bad for her original investment of £3,000. The capture inspired the sea dogs to continue their raids, even if the Madre de Deus would never be matched.

The Crews

In the poorly ventilated, cramped, and not always clean ships of the period, a sailor was far more likely to die from disease than a Spanish cannon shot. Indeed, casualties were often so high that a ship had to be abandoned for want of sufficient crew to sail it. The big attraction, of course, and the reason sailors faced the hazards of sea, disease, and warfare, was the possibility of acquiring loot. Sailors on privateering expeditions were permitted to take whatever they liked that was not from the cargo of a captured ship (that was divided between the captain, officers, and investors, with a tiny sum leftover then shared amongst the ordinary seamen). In reality, it was very difficult to control who grabbed what after a capture, and a quick handful of gold coins or even jewels would have ended a sailor's financial worries for the rest of their lives. Consequently, manning a privateering expedition was not as difficult as finding a crew for a naval vessel where there was no chance of booty. Indeed, so popular was the lure of treasure that there was often a shortage of crews for ordinary fishing vessels in English ports.

The Failures

There were many failures to match the successes. The privateer John Oxenham (c. 1535-1580 CE) tried to take control of Panama through which Spanish silver looted from South America passed in mule trains. Landing on the isthmus in 1576 CE and holding it for a year, Oxenham's fleet was then destroyed by a Spanish fleet, and the Englishmen were captured. Most of the crew were either hanged there and then or sent to work as galley slaves in Spanish ships. Oxenham, meanwhile, was imprisoned in Lima, tortured to ascertain what England's plans were in the Pacific, and then executed in 1580 CE.

Another disaster was the loss of the Revenge, then captained by Sir Richard Grenville (1542-1591 CE). Grenville, typical of the sea dogs, was a man of all-sorts: Member of Parliament, soldier, plantation owner, and mariner. He is best remembered, though, for his courageous if pointless defence of his ship the Revenge when attacked by 56 Spanish ships in the Azores in 1591 CE. Grenville had been lurking in these islands hoping to catch Spanish treasure ships but was surprised by the arrival of a large enemy fleet. The other English ships retreated, and Grenville was left isolated. Valiantly fighting for over 15 hours, the Revenge did much damage but finally succumbed, gaining legendary status in English maritime-lore.

Limitations & Decline

Privateering as a policy of state, then, had some serious flaws. The first was that there was very little coordination between privateering expeditions and captains. Even in the same fleet, there were conflicting objectives as once a captain had acquired the wealth he and his investors had hoped for, he would often return home. Another problem was the lack of any lasting strategic value to such a policy, making profit one year had no effect on the chances of making a profit the next year. There was, too, competition for prizes from French and Dutch privateers and pirates. In addition, the Spanish knew full well the English had few scruples when it came to rich prizes, as the ambassador Guzman de Silva noted, "they have good ships and are greedy folk with more liberty than is good for them" (Williams, 43). Accordingly, the Spanish reacted to the threat posed by privateers and took measures to minimise their damage. Colonial settlements received ever-more impressive fortifications and shore batteries. Although Philip was reduced to sailing his plate fleets at inopportune times of year (resulting in more ships sinking in storms), over time, the use of more powerfully armed escorts and putting new, faster ships together in convoys for better protection was very effective from the early 1590s CE, and by 1595 CE Philip once again had a full navy with which to patrol the seas.

Finally, peaceful and enduring trade was much more lucrative than robbing ships at sea and so the privateers went into decline, even if all-out piracy would reach its heyday in the mid-17th to early 18th century CE when the emergence of the European colonial empires brought new temptations for adventurous mariners eager for easy pickings. The real wealth, though, was to be found in international trade and so the great trading companies arrived such as that colonial giant the East India Company, founded in 1600 CE.

It was the sea dogs, though, who had laid the foundations and shown that England, now withdrawn from the rest of Europe, could steadily build a world empire linked by its fleet of ships. English mariners were now armed with a hugely improved knowledge of winds and tides combined with much more accurate charts and reliable navigational instruments. So, too, the sea dogs had brought social changes. Those who gained wealth from privateering moved up the social ladder, bought estates, and invested in trading ventures and businesses which would become household names. Not only riches had been gained but so, too, new products were introduced and adopted by English people of all classes, notably tobacco, sugar, pepper, and cloves. It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that an Elizabethan galleon appeared on the queen's coinage and remained on English coins of one sort or another until 1971 CE.