During the Elizabethan Era (1558-1603 CE), people of all classes greatly looked forward to the many holidays and festivals on offer throughout the year. The vast majority of public holidays were also religious commemorations, and attendance at service was required by law. Still, the feasts that accompanied many of these 'holy days' were anticipated with pleasure, and many secular traditions began to appear alongside them such as playing football on Shrove Tuesday and giving gifts to mothers on the third Sunday before Easter. Holidays were also an opportunity to visit towns for a local fair or even travel further afield. The Elizabethan period was the first time the idea of a Grand Tour of Europe caught on amongst the rich, seen as a way to broaden a young person's horizons and round off their general education.

Holy Days

The concept of an extended holiday as a period of rest from work is a relatively modern idea. Throughout the Middle Ages, the only time a worker had off work was Sundays and holy days, that is days established by the Church to celebrate a religious matter such as the life of a particular saint or such events as the birth of Jesus Christ at Christmas and his resurrection at Easter. In the 16th century CE, these holy days became known by the now more familiar and wholly secular term, 'holidays'. The Elizabethan period was also the first time that such religious holidays came to be associated less with Church services and more to do with taking a 24-hour break from everyday life and, if possible, enjoying a little better quality of food and drink than one usually consumed. However, it is to be remembered that attendance at church on the main holy days was still required of everyone by law.

In the second half of the 16th century CE, there were 17 principal holy days recognised by the Anglican Church, some of which, as today, moved particular dates depending on the lunar calendar. These holy days, and their celebratory or commemorative purposes, were:

- New Year's Day (1 Jan) - the Circumcision of Jesus Christ.

- Twelfth Day (6 Jan) - the Epiphany when the Magi visited Jesus.

- Candlemas (2 Feb) - Feast of the Purification of Mary.

- Shrovetide/Shrove Tuesday (between 3 Feb & 9 Mar) - the last day before the fasting of Lent.

- Ash Wednesday (between 4 Feb & 10 Mar) - First day of Lent, the 40-day fast that leads up to Easter.

- Lady Day (25 Mar) - Annunciation of Mary and considered the first day of the calendar year in England (when the year number changed).

- Easter (between 22 Mar & 25 Apr) - the Resurrection of Christ and including nine days of celebration.

- May Day (1 May) - commemorating St. Philip and Jacob but also considered the first day of summer.

- Ascension Day (between 30 Apr & 3 Jun) - Ascension of Christ and a major summer festival.

- Whitsunday (between 10 May & 13 Jun) - Pentecost when Christ visited the apostles.

- Trinity Sunday (between 17 May & 20 Jun) - Feast day of the Trinity.

- Midsummer Day (24 Jun) - also commemorates John the Baptist.

- Michaelmas (29 Sep) - marks the end of the harvest season and commemorates the Archangel Michael.

- All Hallows/Hallowtide (1 Nov) - the feast of All Saints (Hallows).

- Accession Day (17 Nov) - commemorates Elizabeth I of England's accession.

- Saint Andrew's Day (30 Nov) - commemorates St. Andrew.

- Christmas (25 Dec) - the birth of Jesus Christ.

Holiday Traditions & Customs

One might also add Saint George's Day (23 Apr) to the list, which saw the feast of England's patron saint but which was not an official holiday. Besides all of the above, local churches and more traditional-Catholic-sympathetic ones would have celebrated on other days too, especially to commemorate various additional saints and the local patron saint of a town or village. The English Reformation, and especially the Puritan movement, toned down the more showy elements of Catholic celebrations. For example, the impressive procession of candles for Candlemas was largely abandoned. In contrast, various secular traditions came to be associated with these particular holy days. For example, it was customary to give gifts on New Year's Day, have a big get-together involving pancakes and football on Shrove Tuesday (the origins of Mardi Gras), or organise bonfires on Midsummer's Day. During Lent, a Jack-a-Lent effigy was put up and pelted by passers-by with stones, perhaps to ease the frustration of a more limited diet during that period (even if many no longer followed it rigorously). Also during Lent, on the third Sunday before Easter, people traditionally visited or gave gifts to their mothers (hence the modern Mother's Day). The Thursday before Easter, Maundy Thursday, was a time to give charity to those in need.

Both May Day and Whitsunday were an opportunity to hold major summer festivals with feasts, dancing, and plays. Feasts were a major part of holy days and, no doubt, the part most looked forward to by many people. Connected with this fact is the need for preparation time, which is why many holidays came to have their own preceding 'Eve', like Christmas Eve, today's lone survivor. The first step in the preparation was to fast on this eve (usually the evening only), typically avoiding meat. The second step was to prepare the marvellous dishes to be eaten on the big day itself, like the traditional goose eaten on the day of Michaelmas.

Another reason to look forward to holy days was the holding of fairs. Many towns held at least one fair each year, usually in the summer months but sometimes as late as November. A fair could last for one or several days. Here there were agricultural shows, travelling performers of all kinds, plays were put on, military displays were organised, and dances were held. There was, too, the chance to buy goods brought in from travelling merchants from across the country and even abroad such as the wine merchants.

Easter

Then, as now, two holidays stood out for their particularly abundant celebrations, and these were Easter and Christmas. Easter was the most important celebration of the whole year, and by Elizabeth's reign, it had established itself on the first Sunday after the first full moon to appear on or after 21 March. By the time Easter arrived, traditionalists were absolutely ready to celebrate it because they had been fasting for the 40 days of Lent which preceded it. Religious celebrations actually began the week before Easter Sunday on Palm Sunday (the day Jesus entered Jerusalem), although after the Reformation, people no longer brought palm fronds to church on that day. School children were happy, too, as they had two weeks off for the Easter holiday.

Everyone attended church on Easter Sunday, as noted above, and it was the one sure time of the year when even the less-enthusiastic Christians took communion. Priests often kept records of who attended the service in an Easter Book (taking communion at least three times a year was another legal requirement for Elizabeth's subjects). Feasts were held which, of course, offered all kinds of dishes using much-longed-for meat and sweet things. With the reduction in Catholic traditions, there was something of a return to ancient pagan customs, the time of year being spring and so it had always been associated with fertility. Accordingly, eggs and rabbits now make their re-appearance alongside the Christian Easter traditions.

Christmas

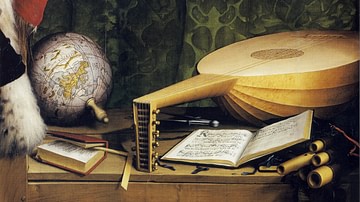

The countdown to Christmas, advent, began on the Sunday closest to 30 November, St. Andrew's Day. Advent was originally meant to be a period of fasting but was becoming less strictly adhered to as the years went by. The holiday itself began on 25 December and lasted 12 days until 6 January. School children had another two weeks off at this time of year. In the Middle Ages, the eve of the 6th, Twelfth Night, witnessed the most important celebrations of the holiday as it was also associated with mid-winter but now the 25th was taking over as the biggest feast day of this holiday period. Homes were decorated with holly, mistletoe, and ivy, while a Yule log was burned over the entire holiday. Special dishes were prepared using more expensive than usual ingredients, especially pies and spiced fruitcakes. Nuts and oranges were other rarities to be enjoyed at this time of year, as was spiced ale known as wassail, and, of course, there was lots of dancing, music, and games.

A Rest From Social Norms

Holidays were not only a break from the usual toil but were often, too, a welcome chance to relax social rules. Such games as reversing the roles of the sexes, making a commoner 'king of the feast' or young apprentices roaming the streets enforcing the laws on their elders were the source of much hilarity. So, too, were the opportunities to drink and be merry, often to excess. However, as the historian J. Morrill points out, "Festive licence, while seemingly transgressing social boundaries, served in reality to underscore expectations about the appropriate behaviour demanded in everyday life" (199). Holidays were but a temporary and all-too-short break from normality. In addition, feasts and celebrations often only emphasised the wide gap between the haves and have-nots. Further, the rich were reinforced in their superior position by the expectation that they display their wealth and feelings of charity by giving to the poor and paying a greater share of the costs of community celebrations.

Travel & the Grand Tour

Although using holidays to travel far and wide and visit new places was hardly a common practice, the Elizabethan period did see the beginnings of this habit. Holy days had always been an opportunity for pilgrims to visit important religious sites, perhaps to see for themselves a holy relic safeguarded in a local church or monastery. There were now, though, more and more instances of travel purely for secular purposes, that is seeing new sights and generally having a good time. Noted attractions in the Elizabethan period were the Golden Hind, sailed by Sir Francis Drake around the world in 1577-80 CE and moored in London or the Tower of London with its Crown Jewels and famous armouries.

Unfortunately, there was no official road system in England in the 16th century CE, most roads were mere dirt tracks, and bridges were often a liability, assuming they had survived the last heavy rains. Consequently, Elizabethan travellers rarely moved around in comfort or at any great speed. Private horse carriages did exist and could be hired by the well-off. Most people preferred simply riding a horse, when around 80 kilometres (50 miles) could be covered in a day. Rivers provided another alternative to the bumpy country roads. For overnight stops, there were taverns (accommodation and only wine served) or inns (accommodation, food and drinks of all kinds served). Unfortunately, there were dangers on the road such as highwaymen, who might have been tipped off by staff working in the inn one had just spent the night at.

Although most travellers would have considered a trip to the annual fair in their local town a major expedition, the richer Elizabethans did begin the tradition of the Grand Tour which became so popular in later centuries. The idea of the Tour was that (especially young) people should spend some months travelling in Continental Europe, visiting the ruins of antiquity and more contemporary Renaissance highlights in order to improve their general education and broaden their outlook on life. Italy, France, and Spain were the most popular destinations. Often not just a sightseeing tour, participants learnt a language or two and spent time with noted teachers of such subjects as art, law, astrology, or even gardening. The Grand Tour was, then, considered ideal training for those interested in a career in politics and diplomacy. It is also undoubtedly true that many young men fled England because of bad debts, to escape problems with the authorities, or simply to satisfy their thirst for adventure and find a new life where every day was a holiday.