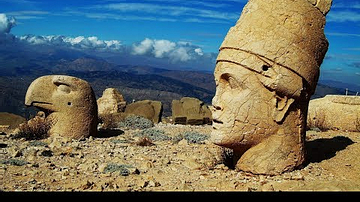

Set within the Anti-Taurus mountain range in southeastern Turkey, beyond the borders of Adiyaman, is the archaeological wonder of Mount Nemrut. Forgotten for centuries, the spellbinding peak of Nemrut Dagi (its Turkish name) has since managed to capture the imagination of thousands of visitors who come annually to witness the pure magic of its landscape at dawn and dusk, when the mighty stone heads glow gold.

Mount Nemrut is located at the heart of what was the Kingdom of Commagene, a small Hellenised Armenian kingdom that carved its place in history from the living rock. In 62 BCE, King Antiochus I (70 - c. 38 BCE), one of the megalomaniacal rulers of this small local dynasty, decided to leave an enduring monument to his greatness and ordered the construction of a tomb-sanctuary on the summit of Mount Nemrut.

Often referred to as the “Throne of the Gods", most people will have seen photos of the huge stone heads atop the mountain, but few know of the history or function of this extraordinary site. Without a doubt, a trip to Mount Nemrut is the highlight of any journey to Commagene, but there is more to discover. Other attractive sites of interest are incorporated into the Nemrut Dagi National Park - the burial site of the royal women at Karakus; the beautifully preserved Cendere Bridge; and the city of Arsameia. All of these places are located close to each other.

Getting There

In July 2017, while travelling around some of Turkey's most historic sites in Cilicia, I set out to explore Mount Nemrut, which had been at the top of my bucket list for many years. It was a five-hour-long drive from my base in Adana to the Karakus Tumulus, the first stop on approaching the National Park from the south.

Travelling in Commagene used to be quite a challenge due to its extremely remote and inaccessible location. Before the building of the road in the 1960s CE, the summit was accessible only by donkey or on foot, which required many hours of riding or walking. Today, many people make the trip to the summit with an arranged tour guide, but independent travellers can use their own transport to get to the top, where shuttles take visitors to the foot of the hill for a small fee. Then, it is a 600-metre (1,960 feet) climb along the processional way leading up to the mountaintop sanctuary.

Antiochus chose the highest mountain peak of his kingdom for his mausoleum. On its summit, at an altitude of 2,150 metres (7,000 feet), he built a high tumulus (artificial mound) that is still visible today in every direction from over 100 kilometres (62 miles) away. According to inscriptions left behind before he died, Antiochus wanted to be buried in a high and holy place among the gods. The king wished to be preserved for eternity, and by all accounts, he succeeded.

However, it was only in 1881 CE that a German road engineer reported the tomb's discovery. Since then, the site has been excavated by many native and foreign researchers. It became the world's highest open-air museum and was included on the prestigious UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987 CE.

The Kingdom of Commagene

The ancient Commagene Kingdom occupied what had been Seleucid territory on the right bank of the Euphrates river. It consisted of the land between the plains of northern Syria and the eastern Taurus Mountains, the portion of southeastern Asia Minor that today roughly corresponds with Adiyaman Province and the north of Gaziantep Province.

Its history begins with the reign of Ptolemaeus of Commagene (201-130 BCE), a Seleucid officer of Orontid Armenian descent who became king around 162 BCE and established himself as an independent ruler. His kingdom controlled the crossings of the Euphrates River from Mesopotamia and several routes over the Taurus Mountains. As a result, it played a significant role as a buffer state between the Seleucid Empire in the west and Parthia in the east. Ptolemaeus was succeeded by his son Sames II (r. 130-109 BCE), who founded the fortress at Samosata.

According to the ancient Greek historian Strabo (c. 64 BCE - c. 24 CE), the kingdom became wealthy from trade and agriculture, particularly on the fertile lands around the capital. As part of a peace alliance between the Kingdom of Commagene and the Seleucid Empire, Mithridates I Callinicus (r. 109-70 BCE), the son and successor of Sames II, was married to the Seleucid princess Laodice VII Thea. Gradually, the kingdom became Hellenized, and Greek was adopted as the official language.

Commagene reached its height in the 1st century BCE under Antiochus I. During his long reign, the Romans waged war against the Parthians, and Antiochus allied himself with the Romans, before forming alliances with the Parthians by arranging the marriage of his daughter Laodice to Orodes II of Parthia (57-37 BCE). Commagene maintained its independence until its annexation by the Roman Empire in 17 CE. It re-emerged as an independent kingdom from 38 CE but was permanently absorbed into the Roman province of Syria in 72 CE when the emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE) deposed Antiochus IV (38-72 CE) for his alleged conspiracy with the Parthians against the Romans.

Antiochus I's Tomb-Sanctuary on Mount Nemrut

Antiochus I - "a just, eminent god, friend of Romans and friend of Greeks" (as his full title goes) - was the son of King Mithridates I Calinicus (109–70 BCE) and Queen Laodice VII Thea of Commagene (b. 122 BCE). Half-Armenian and half-Greek, Antiochus counted himself as a descendant of the Achaemenids on his father's side and the Seleucids on his mother's - two of the greatest dynasties in the ancient world.

The self-obsessed ruler instituted a royal cult and ordered the construction of a tomb-sanctuary (hierothesion) on Mount Nemrut so that he could be worshipped as a god after his death. This extraordinary funerary complex consists of a 50-metre-high (164 feet) artificial mound (tumulus) of crushed limestone, three cult terraces (east, west, and north), and a large altar with a stepped platform. The body of King Antiochus is thought to have been buried in a chamber beneath his man-made mountain, but despite repeated attempts, his tomb has yet to be found.

Visiting the Sanctuary

Visitors access the different terraces via a narrow processional way around the base of the tumulus. The east and west terraces lie on either side and are both dominated by a row of five colossal enthroned statues. Sitting majestically with their back to the tumulus, the figures, between 8 and 10 metres (26-32 feet) tall, have been identified as Antiochus I and a pantheon of Greek, Armenian, and Persian deities that reflected Antiochus' mixed ancestry - Zeus-Orosmasdes-Ahura Mazda, Artagnes-Bahram-Hercules-Ares, Apollo-Mithras-Helios-Hermes, and Commagene-Atargatis-Juno Dolichena.

Their stone heads, tossed to the ground by earthquakes, have been rearranged to help visitors understand who they were. King Antiochus is seated on the left end side. He is dressed in Persian garb and wears an Armenian tiara, while the gods are represented in assorted Greek and Persian apparel. Apollo-Mithras-Helios-Hermes, for example, wears Persian clothes. The goddess Commagene is dressed in the Greek style and holds a cornucopia filled with fruits and flowers (symbolising the fertility of the kingdom).

The blending of eastern and western cultures follows the principle known as syncretism that was propounded by Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) and his successors to help bind the peoples of the former Persian Achaemenid Empire with their Greek conquerors. The enthroned gods were flanked on either side by larger-than-life statues of guardian creatures, a lion and an eagle, and by a group of sandstone slabs representing hand-shaking (dexiosis) scenes of the king with the different deities. Two rows of stelae completed the monument with portraits of Antiochus' Achaemenid and Hellenistic ancestors.

East, West, & North Terraces

The East Terrace is the best-preserved. The colossal enthroned statues stand on a tiered podium, some 7 metres (22 feet) above the terrace, facing toward the sunrise. On the back of these statues, a long inscription carved in Greek details the historical and legal aspects regarding the sanctuary and the establishment of the new cult. Opposite the seated statues are the foundations of what is believed to be a sacrificial altar.

The West Terrace had the same features as those displayed on the East Terrace but was considerably narrower than its eastern counterpart and had no main altar. It is now also more damaged, although the colossal heads are better preserved. The order of the enthroned statues, this time facing the setting sun and standing only 2 metres (6.5 feet) above the terrace, is identical to those of the East Terrace. Alongside the great statues, five superb cult reliefs have survived.

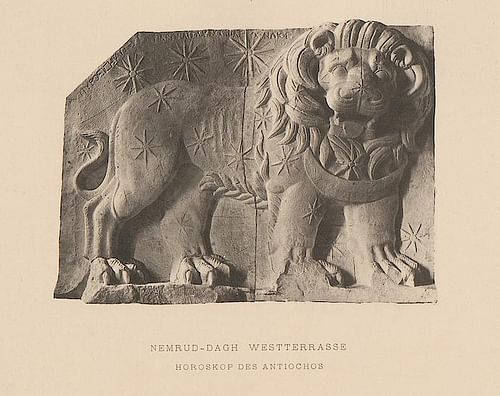

Three of them represent dexiosis scenes showing Antiochus shaking hands with Apollo, Zeus, and Hercules, while the fifth one, the finest, is thought to represent a kind of horoscope, one of the oldest known in the world. It depicts a lion with 19 stars, signifying the constellation Leo, three planets (identified by Greek inscriptions as Mars, Jupiter, and Mercury) and a crescent moon (representing Commagene). Recent research has shown that the lion relief may reflect the situation of the skies at particular events like the coronation of Mithridates I in 109 BCE and his son Antiochus in 62 BCE. All the reliefs have been removed from the site and are stored in the Adiyaman Archaeological Museum. On the far side of the terrace are reliefs of Antiochus' paternal ancestors, who linked him with the Achaemenid royal house.

Between the East and West terraces is the 86-metre-long (282 feet) North Terrace. It is quite narrow and was probably never finished as the stelae lying nearby are all unworked, bearing no inscriptions or figures. There is also no statue. Some scholars have advanced the possibility that this terrace was allocated for the use of kings who would take the throne after Antiochus. However, Antiochus' son, Mithridates II (c. 38-20 BCE), probably decided to halt construction projects on Mount Nemrut and instead turned to his own initiatives, such as the construction of the burial monument at Karakus.

Karakus, the Cendere Bridge, & Arsameia

Upon entering the Nemrut Dagı National Park from the south, the visitor passes a huge tumulus to the left of the road. Like Mount Nemrut, the Karakus Tumulus is an artificial mound, albeit on a more modest scale. It was built by Antiochus' son, Mithridates II of Commagene, as the last resting place of his mother Isias, his sister Antiochis, and his niece Aka I, offering evidence of the importance the Commagene Kingdom placed on women.

The tumulus, about 25 metres (82 feet) in height, was originally encircled by three groups of three Doric columns. Only three columns now remain, topped with an eagle, a lion, and a dexiosis relief of King Mithridates II and his sister Laodice shaking hands. On a clear day, the tumulus on the summit of Mount Nemrut is visible as the highest point to the northeast.

![Tumulus of Karakus [South Side]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/12602.jpg?v=1636186506)

About ten kilometres (6.2 miles) away, the road to Nemrut takes the traveller to one of the best-preserved Roman stone bridges. Known today as Cendere or Severan Bridge, it spans the Cendere River, a tributary of the Euphrates called Chabinas in antiquity. An inscription built into one of its parapets reveals that it was built by the Sixteenth Roman legion (Legio XVI Flavia Firma) in the last years of the 2nd century CE, and was dedicated to the Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE).

There were dedications on the four columns located at each end of the bridge informing us that the financing of the bridge was undertaken by four Commagenean cities (Samasata, Perre, Doliche, and Germaniceia). Two columns were dedicated to Septimius Severus and his wife Julia Domna, while the others were dedicated to their two sons Geta and Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus. The latter eventually reigned as Caracalla (r. 198-217 CE), had his brother Geta (r. 209-211 CE) killed, and erased him from history. Only three columns have survived as Geta's one was removed from the bridge after his assassination.

About 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) onwards from the Roman bridge, a signpost takes the visitor to the ancient Commagene capital of Arsameia where Antiochus built a hierothesion (funerary monument) to his father Mithridates I Callinicus. A path leads uphill to the Acropolis past several free-standing sculptures. The first is a stele of the sun god, Mithras, that originally showed the god shaking hands with King Antiochus. Further along, is another fragmented dexiosis with an unidentified king shaking hands with Mithras and two damaged reliefs depicting Mithridates and Antiochus.

From here, the path climbs to the masterpiece of Arsameia: a superb and perfectly preserved three-and-a-half-metre-high (11.4 feet) dexiosis relief depicting King Antiochus, dressed in Persian attire and wearing the Armenian tiara. He is shaking hands with the Greek demigod Hercules who is recognisable thanks to his distinctive lion skin and his club in his left hand. Cut into the rock wall below the relief is an inscription, and below that is the entrance to a 158-metre-long (518 feet) tunnel. The inscription, written in five columns in the Greek language, describes the building activities of Antiochus at Arsameia and specifies the ritual celebrations to be practised in honour of his father Mithridates I Callinicus.

From the tunnel, the path climbs a little further to the plateau of the Acropolis where the most imposing buildings of Arsameia once stood. The ruins are scant with a few column bases scattered on the floor and the remains of a staircase of white limestone, but the setting is beautiful, offering scenic views into the valley below.

Tips for Visiting Nemrut

WHEN TO VISIT: May through October is best, though sunrise and sunset will be chilly in the spring and autumn months. The mountain is snow-covered from mid-October to the end of April, and winter weather may make the route close to the summit impassable. Most of the local accommodation also closes during the winter months. The best time to visit is June, July, and August when the temperature at the summit is pleasantly cool. The site attracts lots of visitors at sunrise or sunset when the summit is at its most crowded. The trick is to get there just as the early crowd is leaving or before it arrives for the sunset. Then you may have the place to yourself.

GETTING TO NEMRUT: The Nemrut Dagı National Park can be reached by good paved road either from Adiyaman in the south (86 km/53 miles) or Malatya in the north (96 km/60 miles). There are daily flights operated by Turkish Airlines or AnadoluJet to both cities from Istanbul and Ankara. Adıyaman and Kahta make good bases as both have suitable accommodation. The main centres for organised tours to Mount Nemrut for those who do not have transport are Kahta and Malatya, but it is also possible to book a tour from Cappadocia with overnight accommodation.

WHAT TO BRING: Good shoes for the half-hour walk to the summit, warm and windproof clothing no matter whether you go for sunrise or sunset visits, water, and sun cream if you are visiting during the heat of the day.

WHERE TO STAY: The nearest accommodation options from the summit are in the village of Karadut, situated 10 km (6.2 miles) to the south. I can recommend the Karadut Pension, which has simple but clean small rooms and offers good meals.

This article was originally printed in Issue 21 of Ancient History Magazine.