The Battle of Karbala (10 October 680 CE) was a small-scaled military engagement, fought near the river Euphrates, in modern-day Iraq, which saw the massacre of heavily outnumbered Alid troops under the command of Husayn ibn Ali (l. 626-680 CE and also given as Hussayn) by the army of the Umayyad Dynasty (661-750 CE). Though the battle was one-sided and ended with a decisive Umayyad victory, the fallen soldiers of the Husaynid faction, including Husayn himself have ever since been venerated as martyrs of Islam. This battle also became one of the core reasons for opposition against the Umayyads, who were overthrown around 70 years later in a bloody rebellion. Even to this day, the battle remains one of the central defining elements of Islamic heritage and is commemorated annually through the Ashura festival by Shia Muslims.

Historical Context

It is unclear where exactly in history did the two mainstream branches of Islam, Sunnism and Shi'ism, diverge from each other as distinct sects, however, political tensions had begun to divide up the nascent Muslim community immediately after the death of Prophet Muhammad (l. 570-632 CE). Since the Islamic Prophet did not have any male heirs, the succession of his temporal position became a matter of dispute, and Caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE) assumed control. However, a group called the Shi'at Ali (the party of Ali) favored a son-in-law and cousin of the Prophet, Ali ibn Abi Talib (l. 601-661 CE), the husband of Prophet's daughter Fatimah bint Muhammad (l. 605/615-632 CE) for the position of Caliph. Ali did eventually rise to the status, but it was only after three of his predecessors - Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman - had passed away, and the last one of them had been murdered in cold blood by rebels.

The murder of Caliph Uthman (r. 644-656 CE) destabilized the political situation of the empire, leaving Ali to handle an enormous load on thin ice. Uthman's cousin and the governor of Syria, Muawiya (l. 602-680 CE), later Muawiya I (r. 661-680 CE), refused to settle for anything but justice for this fallen cousin, but when Ali failed to comply with the request, the fissures deepened between the ruler and his subordinate, which resulted into an intense civil war known as the First Fitna (656-661 CE). This war ended only with the death of Ali, who has murdered by a renegade group who once supported him, known as the Kharijites. Thus ended the era of the Rashidun Caliphate (as the first four caliphs are collectively referred to by Sunnis).

Death of Hassan ibn Ali & the Accession of Yazid I

Muawiya's path lay clear after Ali's death and he soon assumed the title of Caliph, unopposed by any other prominent leading figure of the time. Ali's eldest son Hasan (also spelled as Hassan, meaning beautiful) temporarily held onto his father's position but abdicated in Muawiya's favor in return for a high pension. Moreover, Muawiya also agreed on some terms with Hasan, which are collectively known as the Hasan-Muawiya Pact. One of these conditions dictated that the seat would pass onto Hasan if Muawiya predeceased him (and it was likely to happen since he was much older), but fate would have it otherwise.

Some sources dictate that Muawiya treated Hasan and his younger brother Husayn ibn Ali (l. 626-680 CE) with great reverence, and even showered them with gifts and favors. But in 670 CE, Hasan was poisoned by one of his wives for reasons highly debated. There is no direct historical evidence to suggest that Muawiya was involved in the murder, but considering that he stood to gain the most from it and that he would not have been able to appoint his son, Yazid (l. 647-683 CE), as his heir otherwise, it is only natural for historians to look at him with doubtful eyes.

With the death of Hasan, Muawiya considered his agreement with him null and void and actively began seeking support for his son, the future Yazid I (r. 680-683 CE), as his heir apparent, much to the discontent and frustration of notable Muslim figures, including Husayn ibn Ali and Abdullah ibn Zubayr (l. 624-692 CE), the son of Zubayr ibn al-Awam (l. 594-656 CE), a prominent Muslim statesman, and a war veteran.

Historian Firas Al-Khateeb notes at this point:

Muslim historians throughout the ages have speculated as to his reasoning for doing so, especially considering the subsequent opposition that arose to Yazid. However, keeping in mind the historical context of Mu'awiya's time makes it easier to understand why the switch to a hereditary system made sense. Mu'awiya's time as caliph showed the emphasis he placed on political unity and harmony. After the political upheaval of 'Ali's caliphate, Mu'awiya's main challenge was keeping the Muslim world united under one command. (44)

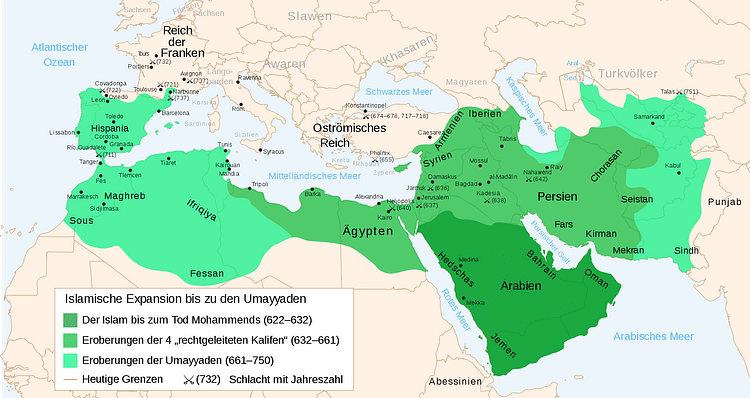

Muawiya's influence prevailed in the end, and the stability he had brought to the empire after years of political tumult following Caliph Uthman's murder allowed Yazid to ascend the throne after his father's death in 680 CE, changing the nature of the future Islamic Caliphates from a semi-republican system of governance to a monarchical one.

The March Towards Karbala

History has not been kind to Yazid I, and the perceptions of contemporary observers were not favorable either: "charges such as enjoyment of singing girls and playing with a pet monkey are brought against him in the tradition" (Hawting, 47). His political ineptness, coupled with distasteful stories of his moral sense, convinced many to stand against his accession. Both Abdullah and Husayn left Medina for Mecca following Yazid's failed attempts to receive their allegiance. Yazid sought to force submission out of his opponents and assume absolute control over the reins of power as his father had done, but he would fail at both.

In Mecca, news reached Husayn that the people of Kufa (in Iraq), his father's capital, which had ever since sunk under the shadows of Damascus, the new caliphal metropolis, were willing to support him and had accepted him as their leader. Husayn decided to oppose Yazid's rule and placed his bet with the Kufans. The plan was to rendezvous with local resistance leaders from Kufa, gather the forces, and raise the standards of rebellion. But nothing would play out this way.

Battle of Karbala

Yazid had caught wind of Husayn's plan by chance and made haste to counteract immediately. He gathered all available soldiers, mustering up a decent-sized force, perhaps in anticipation of a massive rebellion, although this army would only engage in a small-scale skirmish. The estimates for Umayyad forces on this occasion range from a modest 4,000 to a whopping and unbelievable 30,000 strong, modern estimates place the number at about 5,000. Yazid was himself absent from this engagement, as with all other military expeditions during his reign, perhaps to escape the blame for whatever was about to unfold. On this occasion, he handed the command to his cousin Ubaidullah ibn Ziyad (d. 686 CE).

Just a day before the annual hajj pilgrimage, on 9 September 680 CE, Husayn departed Mecca with his family members and around 50 male companions, moving northwards. The party seized a caravan due for Yemen and continued onwards but were met with the news of Kufa's indifference en route. The city had been silenced under the wrath of Ubaidullah; Yazid saw to it that Husayn would receive no aid. Even though they knew the situation well, Husayn's close followers refused to desert him, and the group carried on, intending to show up at the gates of Kufa, hoping that their presence may spark a city-wide uprising.

En-route to Kufa, the group met the vanguard of the Umayyad forces, some 1000 men, who continued to follow them, and on 2 October, the Husaynid forces entered the desert plain of Karbala, where the rest of the Umayyad force arrived by the next day. To force Husayn and his followers into submission, the Umayyads blocked access to the Euphrates River with 500 cavalry troops. A party did manage to fetch some water, but it was no more than 20 waterskins. Some claim that at this point, Husayn presented three proposals to settle the dust:

- Either, they let him return to Mecca

- Or, he be given a border post, away from the rebellious region

- Or, lastly, he be allowed to meet Yazid in person and settle the matter with him

Others have contested the validity of this claim and instead asserted that by this point, Husayn was ready to fight to the death. Both sides prepared for battle on 9 October. Husayn offered his men the option to slip out of the camp under the cover of dusk, but they were not willing to desert him. The Husaynids tied their tents together and dug a defensive ditch behind this line of tents, filled with wood to be set alight if the opponent attacked from the rear. The combatants then stationed themselves in front of the tents, with the ditch and the tents securing all sides but the front.

Husayn's side comprised of 40 infantry and 32 cavalry soldiers, although by some accounts, the number was somewhere around 100 foot and 45 horse-mounted soldiers. In either case, the Umayyad troops vastly outnumbered the Husaynid force. In hand-to-hand combat, however, the Husaynids appear to have bested their foes by some Muslim accounts, but since the event has been quoted with such frequency and blended with fiction over the years, "it is virtually impossible to disentangle history from the legend and hagiography with which it is associated" (Hawting, 50).

However, the resolve of Husayn is beyond all doubts, as historian John Joseph Saunders notes:

Though the odds against him were overwhelming, Husain (Hussayn) determined to die fighting; while his women and children crouched in terror in their tents, he drew out his little band and engaged the enemy. (71)

Fighting commenced on 10 October, when at dawn the Husaynids set the ditch alight and manned their positions, fighting off enemy assaults. Though steadfast, Husayn's forces soon began to wither. The cavalry troops on Husayn's side dismounted when they lost their horses and continued to fight on foot, and forced the Umayyad bands to retreat several times. It was after one such retreat that their foes set Husayn's camp alight, hoping that with the tents burned to the ground, their flanks would be exposed to attack, allowing an encirclement. Sometime after noon, Husayn's companions were surrounded and killed, and many non-combatants rushed to their aid; these were young lads, barely at the cusp of manhood, but were not spared, "his nephew Kasim, a boy of ten, died in his arms; two of his sons and six of his brothers also perished" (Saunders, 71).

Legend has it that even though the Husayn was heavily wounded, having taken an arrow volley straight to his mouth and a heavy blow to his head, he fought his attackers until he was finally beheaded by one of them. The battle was over, around 70 men from Husayn's side lay lifeless on the ground, all of whose bodies were decapitated and their heads sent to Damascus. Husayn's belongings were stolen, his camp looted, and the women and children of his family imprisoned (to be presented before Yazid. Husayn's only surviving son, Ali Zain al-Abidin (l. 659-713 CE), who had not participated in the battle owing to his sickness was spared, but the loss incurred upon the house of Ali was irreparable.

Umayyad casualties were also comparable with 88 dead, all buried before the army moved on, the same courtesy, however, was not extended to the dead of the opposing force. Once the army and the captives had moved on, locals of the surrounding area gave Husayn and his followers a proper burial, without their heads; this site has become enshrined today and is considered a holy site by Shia Muslims, although the Sunnis do not consider Karbala itself to possess any religious value and only lay emphasis in the steadfastness and resilience of Husayn and his supporters.

Aftermath

According to some accounts, when the victorious general was presented with the head of the fallen leader, he poked at it with a stick, which disaffected a soldier amidst his rank, another version of the story states that it was Yazid in Damascus, who did the deed in public and was reprimanded by an old man, barely able to walk, who had been a companion of the Prophet. In either case, Yazid did not mistreat the captives, perhaps fearing that he might be incriminated in the whole affair if he did so, but this turned out to be of no effect. Some say that Yazid even cursed his cousin over the killing of Husayn, stating that he would have spared him had he been there. The women of the fallen imam's household wailed and were even joined by the women of Yazid's family, prompting the sovereign to send them back to Medina, with compensation for the financial losses sustained by them. However, problems for Yazid were far from over.

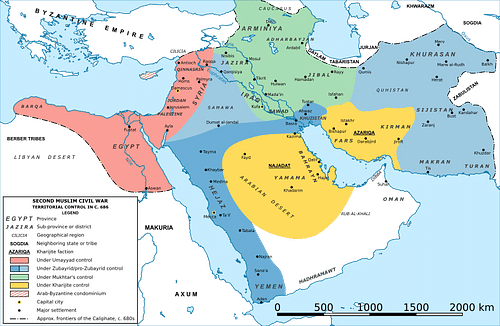

The death of Husayn had the opposite effect of what Yazid may have contemplated. Although the event was initially insignificant, it escalated to inconceivable heights and virtually confined Umayyad rule to the walls of Damascus following Yazid's death and the second civil war of the Islamic Empire, also referred to as the Second Fitna (680-692 CE), erupted. Yazid tried but failed to distance himself from Husayn's death, and the opposition against his rule only grew in intensity.

To preempt a large-scale rebellion, Yazid ordered his troops towards Medina, and the Umayyad forces defeated the natives at the Battle of al-Harra (683 CE), which was followed by the sacking of the city. The Syrian forces then advanced towards Mecca, where Abdullah ibn Zubayr had established himself as the de facto ruler of the region. The siege of Mecca was cut short by Yazid's untimely death, but amidst the fight, the cover of the Ka'aba caught on fire (the holiest site of Islam, presumably built by Abraham and Ishmael for the first time). Abdullah proclaimed himself the Caliph (r. 683-692 CE) from Mecca and extended his control over Hejaz, Iraq, and Egypt. Yazid's death had left his successors barely in control of Damascus, and his son, Muawiya II (r. 683-684 CE) died only a few months after assuming the office – in that time, it is said that he had distanced himself from his father's actions and expressed grief over the fate that befell the Alids.

In Kufa, a rebel named Al-Mukhtar (l. c. 622-687 CE) assumed control in 685 CE. Initially a subordinate to Abdullah, Mukhtar received complete support when an Umayyad army attacked Kufa, but he would later reveal ambitions of his own. Ubaidullah, who had led the troops on Karbala, and who was defeated in the attack on Kufa, was put to the sword there and then. Mukhtar also systematically hunted down people involved in Husayn's death but brought his end upon himself when he parted ways with his sovereign, who retaliated with an attack on his capital in 687 CE.

With Mukhtar out of the way, the Umayyads only had to deal with Abdullah, who died defending Mecca from an Umayyad attack in 692 CE, ending the Second Fitna. The Umayyads managed to preserve their sovereignty for little less than six decades from this point on. Since the seeds of discord had been sown at the field of Karbala, they soon germinated in the form of the Abbasid Revolution (750 CE), which ousted the Umayyads from power and subjected their living and dead to the most horrendous treatment that had been seen in the Islamic Empire.

Legacy

Husayn's death sparked continuous resentment against the Umayyads, even long after Yazid's death. One of the biggest reasons why the Abbasid Revolution was successful was because they successfully harvested the negative emotions of the empire's Shia population. Even long after, Husayn's example was quoted repeatedly in Islamic history and has been considered iconic even by western historians.

Husayn's death has become central to the belief of Shi'ism and holds a special place in the Sunni belief, too; both consider him a martyr who fought against oppression even when things were hopeless. His example has become so universal that Husayn is a popular name for children among both Sunni and Shia Muslims. Conversely, the name Yazid is taboo in the modern era, however, it did not become so immediately after the event.

To this day, Husayn's death anniversary, 10th of Muharram in the Islamic calendar, is commemorated in the annual Ashura festival (Ashura means "the tenth day") by the Shia community which spans the 9th and 10th of the said month. They express the feeling that this event inspires through ritualistic chest-beating and self-flagellation and hymn praises of Husayn while shunning and publicly cursing his offenders. While the Sunni Muslims do share in this sentiment, they denigrate this atmosphere of mourning Husayn's death and consider it contrary to the values that he stood for: honor, commitment, bravery, and faith. They also object to the fact that in all criticisms of the Umayyads, however justified they are, the Kufans (who deserted Husayn) are mostly left untouched.