Batavian revolt was a rebellion of the Batavians against the Romans in 69-70 CE. After initial successes by their commander Julius Civilis, the Batavians were ultimately defeated by the Roman general Quintus Petillius Cerialis.

The year of the four emperors

A century had passed since the emperor Augustus (27 BCE-14 CE) had changed the Roman republic into a monarchy, and the inhabitants of the empire had grown accustomed to one-man rule. As long as the emperor was a capable man, like Augustus, Tiberius, or Claudius, the new system of government worked reasonably well. However, problems would arise when a less talented man would be in charge of the empire.

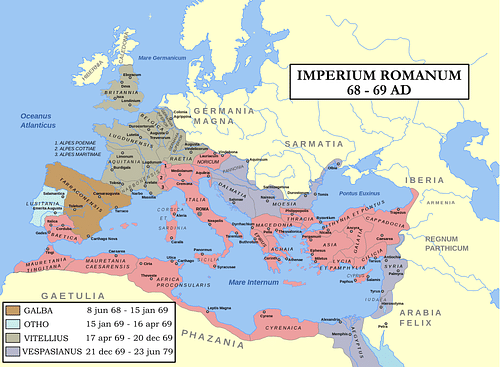

During the reign of Nero (54-68 CE), the provinces were peaceful and prosperous, but when the emperor started to behave like a despot, the senators, who were as governors responsible for the provinces, suffered heavily. One of them was Gaius Julius Vindex, an Aquitanian prince who had entered the Senate and was now governor of Gallia Lugdunensis. In the winter of 67/68 CE, he decided to put an end to the oppression. Being a senator, he tried to do this constitutionally, so he first searched for a worthy successor to the throne. In April 68 CE he found his man: the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, Servius Sulpicius Galba. Now, he started an insurrection.

Vindex' revolt was a disaster. The commander of the Roman legions in the province Germania Superior, Lucius Verginius Rufus, fearing a native rising in Gaul, ordered his men to march from the Rhine to Besançon, where the rebels had their headquarters. Vindex was unable to explain his motives, and having lost the propaganda battle, he lost the real battle and his life (more).

Meanwhile, Nero had panicked and made himself impossible. In June, the Senate had recognized Galba as the new ruler of the empire, and Nero had committed suicide. Among those who did not share the almost universal rejoicing, were the soldiers of the armies of the Rhine in Germania Inferior and Superior. They thought they had done a good job by suppressing the revolt of Vindex, but now discovered that their courageous deeds were explained as an attempt to obstruct the accession of Galba. The fact that Verginius Rufus was immediately replaced (by Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus) did little to ease the discontent.

The native population made more or less the same discovery. They had prudently sided with the legions of the Rhine, but were now suspected by the emperor. For example, Galba dismissed the Batavian cavalry that guarded the emperor's life. This dishonorable discharge did little to improve the situation in the Rhineland.

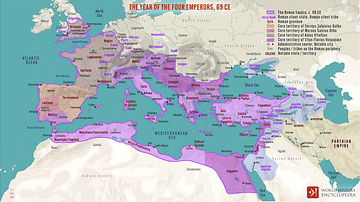

In January 69 CE, matters came to a head, when the soldiers of the army of Germania Inferior proclaimed their commander Aulus Vitellius emperor. Like Nero, Galba was unable to cope with a rival. He panicked, offended important senators, and incurred the wrath of the soldiers of the Praetorian guard, who lynched him on the Forum. He was succeeded by a rich senator named Marcus Salvius Otho, who inherited the war against Vitellius.

He did not long enjoy his position. Negotiations between the two emperors failed, and Otho's army was no match for the experienced soldiers of Vitellius, who had -moreover- received support from the legions of Germania Superior and Britannia. In April, Otho was defeated on the plains of the river Po, and committed suicide (more).

Vitellius was now sole ruler in the Roman world. However, he had taken a large army with him to Italy, and had left behind only a quarter of the legionaries. The Rhine was virtually unguarded. Almost immediately after he had occupied Rome, Vitellius sent back military units.

Among these were eight auxiliary units of Batavian infantry which had fought bravely on the Po plains. They had already reached Mogontiacum (modern Mainz) when they received orders to return to Italy. Again, they had to assist Vitellius, this time in his struggle against a new pretender, the commander of the Roman forces in Judaea, Titus Flavius Vespasianus, better known as Vespasian. After Galba, Vitellius, and Otho, he was the fourth emperor of the long but single year 69 CE.

The conspiracy

Vitellius had become emperor and needed soldiers to defend himself against general Vespasian, who was marching on Rome from Judaea. Eight Batavian auxiliary infantry units were on their way to Italy, but the emperor still needed more men. Therefore, he ordered the commander of the Rhine army, Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus, to send extra troops.

Our main source for the events in the years 69 and 70 CE, the Histories of the Roman historian Tacitus (c.55-c.120 CE), is extremely negative about general Flaccus. Tacitus thinks he was indolent, insecure, slow, and responsible for the Roman defeats in 69. However, in his description of the Batavian revolt, he constantly opposes the civilized but decadent Romans and the savage but noble Batavians (a trick he also employs in his Origins and customs of the Germans). His idealized portrait of the leader of the Batavians, the brave Julius Civilis, is mirrored in the portrayal of Flaccus as an incompetent defeatist. They are extreme types.

Of course it is possible that Flaccus was really incompetent, but if we ignore Tacitus' personal judgments and carefully look at what the commander of the Rhine army actually did, there is no reason to doubt that he was a capable commander who did what he could in a very difficult situation.The least one can say for Flaccus, is that he sensed that the Batavians had become restless, and understood that trouble was in the air. Therefore, he refused to support Vitellius, seeing that it was ill-advised to remove more soldiers from the border.

After Flaccus' refusal, Vitellius demanded that new soldiers would be recruited. This measure was meant as a deterrent to future rebels and might have worked well, but no Batavian was impressed by the measure, as there were no troops in the neighborhood to implement the treath. Tacitus writes:

Batavians of military age were being conscripted. The levy was by its nature a heavy burden, but it was rendered still more oppressive by the greed and profligacy of the recruiting sergeants, who called up the old and unfit in order to exact a bribe for their release, while young, good-looking lads (for children are normally quite tall among the Batavians) were dragged off to gratify their lust. This caused bitter resentment, and the ringleaders of the prearranged revolt succeeded in getting their countrymen to refuse service. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.14;

tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

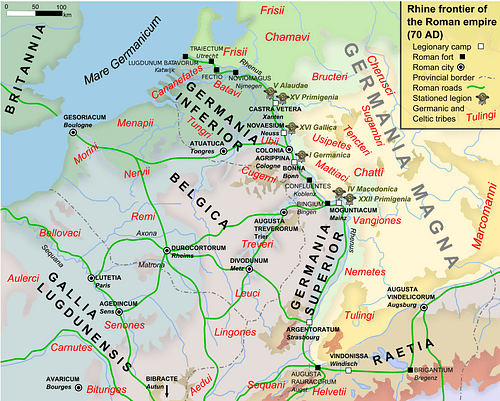

The Batavians lived along the great rivers in the Netherlands on a large island between the rivers Waal and Rhine. (Their name lives on in the present name of the island, Betuwe.) The Island was a relatively poor country, which could not be exploited financially by the Romans. Therefore, the Batavians contributed only men and arms to the empire: eight auxiliary units of infantry, one squadron of cavalry, and -until the Galba dismissed them- the mounted bodyguard of the emperor. Demographic research has led to the conclusion that every Batavian family had at least one son in the army. Recruiting more men was almost impossible, and it comes as not surprise to find the sergeants calling up the old, the unfit, and the young. Tacitus continues his story.

Julius Civilis invited the nobles and the most enterprising commoners to a sacred grove, ostensibly for a banquet. When he saw that darkness and merriment had inflamed their hearts, he addressed them. Starting with a reference to the glory and renown of their nation, he went on to catalogue the wrongs, the depredations and all the other woes of slavery. The alliance, he said, was no longer observed on the old terms: they were treated as chattels. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.14; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

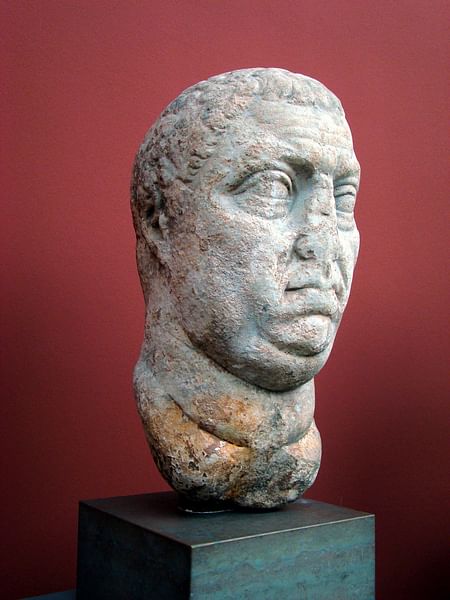

Julius Civilis was a Roman citizen and a member of the royal family that had once ruled the Batavians. Later, the constitution had changed and they now had a summus magistratus ('highest magistrate'), but the family of Civilis was still very important and influential. He had fought in one of the Batavian auxiliary units in the Roman army during Claudius' invasion of Britain, and was still commanding a unit. Tacitus calls him 'unusually intelligent for a barbarian', which is a commonplace that Roman authors used to describe non-Romans who had surprised them (e.g., the Roman author Velleius Paterculus uses more or less the same words to describe Arminius, who had defeated the Romans in the Teutoburg Forest; and the Greek author says the same about the Thracian Spartacus.)

Julius Civilis and his brother Claudius Paulus -again a name that shows that the man possessed the Roman citizenship- had been arrested in 68 CE on a charge of treason. According to Tacitus, the charge was trumped up. We do not know the precise nature of the accusation, but we do know the result: Paulus was executed and Civilis was pardoned when Galba became emperor. In the last weeks of 68, Civilis had returned to the area later known as Germania Inferior, where he was again arrested, and brought to the new governor, Vitellius. This time, there is no reason to doubt that Civilis was guilty of conspiracy; however, Vitellius had pardoned him as a gesture towards the Batavians. In this way, he hoped to gain the support of their eight auxiliary units. A few weeks later the soldiers indeed sided with Vitellius, and as we have already seen, they took part in the march on Rome.

The banquet in the sacred grove illustrates that the Batavians were only partially romanized - or Tacitus wants us to believe this. Otherwise, they would have gathered in a town hall. Tacitus' words remind one of what he writes in his Origins and customs of the Germans.

It is at their feasts that the Germans generally consult [...], for they think that at no time is the mind more open to simplicity of purpose or more warmed to noble aspirations. A race without either natural or acquired cunning, they disclose their hidden thoughts in the freedom of the festivity. Thus the sentiments of all having been discovered and laid bare, the discussion is renewed on the following day, and from each occasion its own peculiar advantage is derived. They deliberate when they have no power to dissemble; they resolve when error is impossible. [Tacitus, Origins and customs of the Germans, 22; tr. A. J. Church and W. J. Brodribb]

This description of the Germanic way of consultation is highly suspect. Like all Greek and Roman authors, Tacitus was obsessed with the opposition between civilization and barbarism. The Romans and Greeks considered themselves to be civilized, and because they lived in the center of the earth's disk, it could reasonably be assumed that only savages dwelt on the edges of the earth. Since the Greeks and Romans lived on river plains, it was quite obvious that barbarians dwelt in the mountains and forests. (See below; Tacitus even describes the Dutch coast as rocky; Annals, 2.23.3) This explains why the Romans and Greeks always mention forests, even when there were no forests at all. As a matter of fact, pollen research has shown that the Dutch river country were hardly wooded in the Roman age. This does not mean that there never was a banquet in a sacred grove, but that we must be cautious. Tacitus wants to show that the Batavians were noble savages, and is not necessarily telling the truth.

Another feature of ancient descriptions of far-away people, is that they often resemble each other - after all, they were all living on the edge of the earth. The custom of making a double judgment - one when drunk, one when sober- is also known from another source, the Histories of the Greek researcher Herodotus of Halicarnassus (1.133), who correctly says that it is a Persian custom. Again, this does not mean that the Germans did not consult each other in a state of inebriety, but it warns us that we must remain careful when we read the extremely tendentious Histories of Tacitus.

Causes of the rebellion

It is too easy to explain the Batavian revolt from the two motives that we discussed in the preceding part of this article: the forced recruitment (above) and the presence of a prince with a grudge. There has to be a deeper cause; after all, if the Batavians were content with Roman rule, they would have accepted the forced recruitment as an unpleasant but temporary measure, and would not have followed Julius Civilis. We must admit that we do not know this deeper cause, but we can make some educated guesses, and make a list of contributing factors.

In the first place, Julius Civilis had at least two powerful personal motives. Tacitus mentions the -perhaps unlawful- execution of Civilis' brother Paulus, which must have been sufficient for anybody to start looking for revenge. An additional motive may have been the restoration of royal power. As we have already seen (above), Julius Civilis belonged to the leading Batavian family, and his ancestors had been kings. It is impossible that the thought about restoration did not cross Civilis' mind. This motive, however, is not mentioned by Tacitus.

He does, however, quote from a speech by the Batavian leader, in which he presented the corrupt recruitment practices as proof for the fact that the Romans did not consider the Batavians to be allies, but subjects ('the alliance is no longer observed on the old terms: we are treated as chattels'). Unfortunately, we can not establish whether Civilis really said something like this, and we have the right to be doubtful. After all, how can Tacitus possibly have known what Civilis had said? Besides, the corruption of decadent Roman magistrates is one of Tacitus' leading themes. We may reasonably assume that the speech of Civilis, in which he focuses on the rupture of the alliance, is an invention. It is too legalistic.

Nonetheless, the levy was a heavy burden. We already noticed (above) that every Batavian family had at least one son in the army, and that Vitellius was demanding too much. There is no reason to deny that this was one of the factors that contributed to the outbreak of the war.

Sometimes, Tacitus makes the Batavian leader say that he is defending the freedom of his compatriots. Unfortunately, in ancient literature, barbarians are always thirsting for freedom. The motive is highly suspect. An additional complication is that we do not know what is meant with 'freedom'. Were the Batavians looking for real independence and autonomy? Or was Julius Civilis trying to give more power to the Batavian elite?

There is some evidence that may corroborate the last hypothesis. The old aristocracy of the tribes now living in the Roman empire, had received the prestigious Roman citizenship several generations ago. Those who had been patronized by Julius Caesar and the emperor Augustus, had as family name Julius, plus an additional personal surname (e.g., Julius Civilis). But a new generation was becoming influential. They had received the citizenship from Tiberius, Claudius, or Nero, and had Claudius as their new family names (e.g., Claudius Labeo). There may have been some tension between the first and second generation, because the 'old Romans' were probably not happy to share their power with the newcomers; as we will see below, one of Julius Civilis' personal enemies was a Claudius. It is possible that Civilis wanted to restore the rights of the old aristocracy.

There may have been a religious motive, because we know that a Bructerian prophetess called Veleda predicted the victory of the Batavians. Later, she was awarded with the Roman commander Munius Lupercus (as slave) and the flagship of the Roman navy. However, it is not known whether she incited the rebels or merely predicted victory.

It may also be noted that the Batavian revolt does not belong to the 'normal' rebellions of the first century, like that of Julius Florus and Julius Sacrovir in Gaul in 21 CE, that of queen Boudicca in Britain in 60 CE, and that of the Jews in 66 CE: these were caused by oppressive taxes. The Batavian revolt was not caused by financial troubles. (It comes as a surprise that of all people in the world, the money crazy Dutch regard the Batavians as their ancestors.)

So we are left with several -sometimes conflicting- factors that may have played a role. Julius Civilis wanted to avenge his brother and may have wanted to become king; the old tribal elite may have wanted to regain its former power; and perhaps the tribe as a whole dreamed of an independent state - something that the Frisians and Chauci, two tribes in the north, had obtained in 28. What bound them together, was bitter resentment because of the oppressive recruitment.

Into the vortex

Julius Civilis still commanded one of the Batavian auxiliary units in Roman service, and the commander of the Rhine army, Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus, did not know that Civilis conspired against Rome (although he sensed that something was going on; above). This offered Civilis an opportunity: he induced the Cananefates, the tribe that lived between the Batavians and the sea, to revolt, hoping that Flaccus would send him to suppress the rebellion. Tacitus tells how the war against the Romans started in August of 69.

Among the Cananefates was a foolish desperado called Brinno. He came from a very distinguished family. His father had taken part in many marauding exploits [...]. The mere fact that his son was the heir of a rebel family secured him votes. He was placed upon a shield in the tribal fashion and carried on the swaying shoulders of his bearers to symbolize his election as leader. Immediately calling upon the Frisians, a tribe beyond the Rhine, he swooped down on two Roman auxiliary units in their nearby quarters and simultaneously overran them from the North Sea. The garrison had not expected the attack, nor indeed would it have been strong enough to hold out if it had, so the posts were captured and sacked. Then the enemy fell upon the Roman supply-contractors and merchants who were scattered over the countryside with no thought of war. The marauders were also on the point of destroying the frontier forts, but these were set on fire by the commanders because they could not be defended. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.15; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

Among the two camps that Brinno destroyed was that of the Third Gallic cavalry unit at Praetorium Agrippinae (modern Valkenburg near Leiden), where archaeologists have discovered the burning layer. Among the other frontier forts that were destroyed by the Romans themselves, was Traiectum (modern Utrecht). A telling detail is the treasure of fifty gold pieces that was buried by an officer who was never able to recover his money. (They were rediscovered in 1933 CE in the ruin of the house of a centurio.) Tacitus continues his story:

The headquarters of the various auxiliary units and such troops as they could muster rallied to the eastern part of the Island under a senior centurion named Aquilius. But this was an army on paper only, lacking real strength. It could hardly be otherwise, for Vitellius had withdrawn the bulk of the units' effectives. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.15; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

By lucky coincidence, this Aquilius is known to us from an archaeological discovery: a small silver disk or medal that was discovered in a cavalry base (the 'Kops Plateau') east of the Oppidum Batavorum, the capital of the Batavians (modern Nijmegen). The man's full name was Gaius Aquillius Proculus, and he belonged to the Eighth legion Augusta, which was not stationed in the Germanic provinces.

This is a very important find, because it vindicates the Roman general Flaccus. If a senior centurion was present in Nijmegen, Flaccus had already sent reinforcements, which can only be explained if we assume that he expected trouble among the Batavians. Tacitus' story that Brinno's attack was a surprise, is misleading: the Romans were indeed caught off-guard because they did not expect a Cananefatian rebellion, but they were aware of the increasing tensions.

Civilis decided on a ruse. He took it upon himself to criticize the commanders for abandoning their forts, and offered to deal with the outbreak of the Cananefates in person with the help of the unit under his command. As for the Roman commanders, they could get back to their respective stations. But the Germans are a nation that loves fighting, and they did not keep the secret for long. Hints of what was afoot gradually leaked out and the truth was revealed: Civilis' advice concealed a trick. Scattered units were more liable to be wiped out, and the ringleader was not Brinno, but Civilis. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.16; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

Here we meet Tacitus at his most malicious. He does not mention the Roman commander who saw through Civilis' stratagem and investigated what was going on, but it must have been someone higher in the military hierarchy than Civilis - in other words, Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus. In the sequel of Tacitus' story, his description of the defeat of Aquilius, we see how the Romans are reinforced by ships. Guess who was responsible for sending them.

When the plot came to nothing, Civilis resorted to force and enrolled the Cananefates, Frisians and Batavians in separate striking forces. On the Roman side, a front was formed at no great distance from the Rhine, and the naval vessels which had put in at this point were arrayed to face the enemy. Fighting had not lasted long before a Tungrian unit went over to Civilis, and the Roman troops, disarrayed by this unforeseen treachery, went down before the combined onslaught of allies and foes. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.16; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

The Tungrians where a romanized tribe that lived in the east of what is now Belgium, where their name lives on in the town called Tongeren. To the Romans, their desertion during this battle (which must have taken place south of modern Arnhem) was alarming, because it suggested that auxiliary units that were recruited among otherwise loyal tribes, could be unreliable. However, they and the depleted legions were the only soldiers Flaccus could use. Even worse, volunteers from the northern provinces and the Germanic tribes across the Rhine sided with Civilis.

This success earned the rebels immediate prestige, and provided a useful basis for future action. They had obtained the arms and ships they needed, and were acclaimed as liberators as the news spread like wild-fire thought the German and Gallic provinces. The former immediately sent an offer for help. As for an alliance with the provinces of Gaul, Civilis used cunning and bribery to achieve this, returning the captured commanders of the auxiliary units to their own communities and giving the men the choice between discharge and soldiering on. Those who stayed were offered service on honorable terms, those who went received spoil taken from the Romans. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.17; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

The Romans were now expelled from the country along the rivers Maas, Waal, and Rhine. The cavalry base at the Kops Plateau is the only Roman camp that has no burning layer, which suggests that the Romans were able to keep it, and still controlled the Waal crossing near Nijmegen.

Up till now, the war had, on the Roman side, been waged by auxiliaries: lightly-armed troops that were recruited among the native population and were no match for the Batavians, who were in the majority. Flaccus' reply to their defeat was to send in the legions, heavily-armed infantry men. The Fifth legion Alaudae and the Fifteenth legion Primigenia left their base at Xanten, together with three auxiliary units: Ubians from modern Cologne, Trevirans from modern Trier, and a Batavian squadron. Flaccus and the commander of the expeditionary force, a senator named Munius Lupercus, may have had their doubts about the Batavian squadron, but they knew that it was commanded by a personal enemy of Julius Civilis, a man named Claudius Labeo, and they decided to rely upon his word. Late August, the legions invaded the Island of the Batavians. Somewhere north of Nijmegen, they encountered the Batavian army.

Near Civilis were massed the captured Roman standards: his men were to have their eyes fixed upon the newly-won trophies while their enemies were demoralized by the recollection of defeat. He also caused his mothers and sisters, accompanied by the wives and young children of all his men, to take up their station in the rear as a spur to victory or a reproach to the routed. Then the battle chant of the warriors and the shrill wailing of the women rang out over the host, evoking in response only a feeble cheer from the legions and auxiliary units. The Roman left front was soon exposed by the defection of the Batavian cavalry regiment, which immediately turned about to face us. But in this frightening situation the legionaries kept their arms and ranks intact. The Ubian and Treviran auxiliaries disgraced themselves by stampeding over the countryside in wild flight. Against them the Batavians directed the brunt of their attack, which gave the legions a breathing-space in which to get back to the camp called Vetera [i.e., Xanten]. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.18; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

At this stage, the base at the Kops Plateau was taken over by the Batavians. It is possible that the absence of traces of violence means that this was the camp of the Batavian cavalry regiment that changed sides. Whatever the precise interpretation, the last garrison was now removed from the country of the Batavians. It was a tremendous blow to Roman prestige. An army of some 6,500 men, which included legionaries, had been defeated. Julius Civilis must have been a happy man, but he was not in the mood for generosity. He did not honor Claudius Labeo, who had played such an important role in the Batavian victory, but had him arrested. He still hated his enemy, one of the Claudii that threatened the position of the old aristocracy of the Batavians (above), and sent him to a place of exile among the Frisians in the north, far from any future theaters of operation.

Whatever the war aims of the rebels, they had been reached. The presence of hundreds of dead bodies proved beyond doubt that Julius Civilis had avenged his brother. The tribe had punished the Romans for the dishonorable discharge of the imperial bodyguard and the forced recruitment. Moreover, the Batavians were now regarded as the most powerful tribe in the area. If Julius Civilis wanted to be king of his tribe, he had it within reach: someone who had defeated two legions had sufficient prestige to be any tribe's leader.

The Batavians had gained their freedom, and they knew that the Romans would recognize their independence and would not retaliate. Civilis possessed a letter from Vespasian, the commander of the Roman forces in Judaea who had revolted against the emperor Vitellius. In this letter he asked Civilis, with whom he had fought during the British wars, to revolt. In that way, Vitellius could employ all his troops against Vespasian. Civilis had done precisely what Vespasian had requested him to do -although for other reasons- and the Batavians were justified in their hope that Vespasian would recognize their independence. After all, the emperor Tiberius had in a similar situation, in 28, allowed the Frisians and Chauci their autonomy.

Julius Civilis had reached everything he wanted, but within weeks he had made the fateful decision that was, within a year, to be his undoing.

The siege of Xanten

As we have seen in the preceding article, Julius Civilis and the Batavians had reached everything they wanted: an independence that would be recognized by Vespasian (provided that he won the civil war against the emperor Vitellius), and revenge for the oppressive recruitment by the Romans and the death of Civilis' brother.

The only thing they should never do, was attack the base of the two Roman legions at Xanten - no emperor could leave an attack on this symbol of Roman power unpunished. If only one spear would be thrown across the walls of the legionary base, it was inevitable that a large army would come to the north and make up for the humiliation. Of course, the civil war had to be over, but whoever would be its victor, he was obliged to punish the attackers. Everybody knew that almost three years before, the Jews had attacked the Twelfth legion Fulminata, and that the Romans had retaliated ferociously. Julius Civilis, who had fought in the Roman auxiliaries and was a Roman citizen, certainly must have known.

And yet, at the end of September 69 CE, the Batavians launched an attack on Xanten, or, to use its ancient name, Vetera. The moment was well-chosen: two weeks earlier, the army of the Danuba had sided with Vespasian and now threatened Italy. If there was to be a Roman retaliation, it would be postponed for some time. So, Julius Civilis died his hair red, and swore that he would let it grow until he had destroyed the two legions. We do not know what made him sign his own death sentence.

Whatever the reasons, the Batavians were well-prepared, because they had received the best of all possible reinforcements: the eight auxiliary units that had fought for Vitellius in Italy in the Spring, were sent back to defend the Rhine, and had been recalled for the struggle against Vespasian (above). In the preceding year, they had fought against the levies of Gaius Julius Vindex, and still earlier, they had been stationed in the war zone in Britain. These men knew how to fight, and had more battle experience than most legionaries. Civilis' messenger had reached them while they were already marching to the Alps, and had easily convinced them that they had to side with the independent Batavians.

Let us, before we discuss the Batavian attack on Xanten, see what had happened to the eight auxiliary units. The supreme commander of the Roman forces in Germania Superior and Germania Inferior, Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus, had allowed them to pass Mogontiacum or Mainz.

He called his tribunes and centurions together and consulted them on the desirability of bringing the insubordinate troops to heel by force. But he was not by nature a man of action, and his staff were worried by the ambiguous attitude of the auxiliaries and the dilution of the legions by hasty conscription. So he decided against risking his troops outside the camp. Afterwards, he changed his mind, and as his advisers themselves went back on the views they had expressed, he gave the impression that he intended pursuit, and wrote Herennius Gallus, stationed at Bonn in command of the First legion, telling him to bar the passage of the Batavians and promising to follow closely in their heels with his army. The rebels could in fact have been crushed if Hordeonius Flaccus and Herennius Gallus had moved from opposite directions and caught them between two fires. But Flaccus abandoned his plan, and in a fresh dispatch to Gallus warned him not to molest the departing units. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.19; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

It is unclear what really happened. Tacitus obviously blames Flaccus for not destroying the eight units, but things were more complicated than he indicates. We must remember that Germania Inferior, which was threatened by the Batavians, was not an important province; Germania Superior and Gallia Belgica, however, were. Probably, Flaccus wanted to leave the problem in the periphery, and allowed the Batavians to return home. Then, the war would remain somewhere in the north, where it did not threaten vital Roman interests. This attempt to localize the war where it did not hurt could have been a successful strategy, but, as we will see below, Flaccus was murdered, after which everything went wrong.

A second point is that both Roman armies in Mainz and Bonna (modern Bonn) were smaller than the eight auxiliary units. Only when Flaccus and Gallus were able to attack simultaneously, they were in the majority and could be victorious. Flaccus could not afford that both armies were defeated. Finally, there was a more important war going on in Italy, and he could not move too far to the north. So he decided upon this strategy: keep the vital base of Mainz at all costs, try to keep Xanten, and wait until the civil war is over.

It was sound reasoning, but it implied some risk for the garrison at Xanten, which was commanded by the Munius Lupercus we already met above. The siege started at the end of September 69 CE.

The arrival of the veteran auxiliary units meant that Civilis now commanded a proper army. But he still hesitated on his course of action, and reflected that Rome was strong. So he made all the men he had swear allegiance to Vespasian, and sent an appeal to the two legions which had been beaten in the previous engagement [above] and had retired to the camp at Xanten, asking them to accept the same oath.

Back came the reply. They were not in the habit of taking advice from a traitor nor from the enemy. They already had an emperor, Vitellius, and in his defense they would maintain their loyalty and arms to their dying breath. So it was not for a Batavian turncoat to sit in judgment on matters Roman. He had only to await his deserts - the punishment of a felon.

When this reply reached Civilis, he flew into a rage, and hurried the whole Batavian nation into arms. They were joined by the Bructeri and Tencteri, and as the tidings spread Germania awoke to the call of spoil and glory. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.21; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

Thus started the siege of Xanten. Some 5,000 legionaries, belonging to the already defeated Fifth legion Alaudae and Fifteenth legion Primigenia, defended their camp. Tacitus mentions the presence of the commander of the Sixteenth legion Gallica, which shows that Xanten had been reinforced with men from Neuss. However this may be, the Romans were in the minority. The Batavians had reasons to be optimistic, not in the least because they possessed eight well-trained units, and because Julius Civilis had been training his men along Roman lines. (It is too romantic to think of the revolt as a war between barbarian Batavians and disciplined Romans. In fact, two Roman armies were fighting each other.)

The camp at the Fürstenberg near Xanten was large (56 hectares) and modern - it was only ten years old and well-equipped. Archaeologists have discovered the walls (made of mud brick and wood), foundations of wooden towers, and a double ditch. Besides, the garrison had had time to prepare itself. Tacitus frequently mentions the Roman artillery, which must have possessed a lot of ammunition. He also states that there were no food supplies, which is a bit strange, briefly after the harvest season. In fact, Xanten held out for several months.

The Batavians and their allies first attempted to storm the walls of Xanten, but in vain. Then, they attempted to build siege installations, but they did not have the necessary knowledge. Nonetheless, it shows that they were fighting a 'Roman' war, using Roman siege techniques. Ultimately, Civilis decided to starve the two legions into surrender.

During the siege, Civilis sent out units to plunder towns in Germania Inferior and Gallia Belgica. Germans from the east bank of the Rhine joined in.

The Batavian leader ordered the Ubians and Trevirans to be plundered by their respective neighbors, and another force was sent beyond the Maas to strike a blow at the Menapians and Morinians in the extreme north of Gaul. In both theaters, booty was gathered, and they showed special vindictiveness in plundering the Ubians because this was a tribe of German origin which had renounced its nationality and preferred to be known by a Roman name. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.28; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

In other words, the northern part of the Roman empire was in a state of turmoil. Tacitus plays a very subtle game in these lines. The words 'the Menapians and Morinians in the extreme north of Gaul' [Menapios et Morinos et extrema Galliarum] contain a reference to a well-known line by the poet Virgil, who had called the Morinians the extremi hominum, 'those living on the extreme edges of the earth' (Aeneid 8.727). By using these words, Tacitus remembered his reader of the well-known fact that this was a war against the most savage of all barbarians, which, as every Roman knew, lived on the edges of the world.

The Roman counter-attack

The legions Fifth legion Alaudae and Fifteenth legion Primigenia were besieged in Xanten. Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus, less indolent than Tacitus wants us to believe, had already taken counter-measures. Pickets were posted along the Rhine to prevent the Germans from entering the empire. He ordered the Fourth legion Macedonica to stay at Mainz, which had to be kept at all costs. Messengers were sent to Gaul, Hispania, and Britain, requesting for reinforcements. (As we will see, Basque units were to save the day during a battle near Krefeld.) The Twenty-second legion Primigenia, commanded by Gaius Dillius Vocula, marched at top speed to Novaesium or Neuss in the north; Flaccus himself went to the First legion Germanica at Bonn, traveling on board of a naval squadron because he suffered from gout.

Tacitus tells us that at Bonn, the general found it difficult to take authoritative action. The soldiers held him responsible for the free passage of the eight Batavian auxiliary units (above). However, he convinced the First legion to follow him, and together with Vocula's legion, he joined forces with the Sixteenth legion Gallica at Neuss. They continued to Gelduba, modern Krefeld.

And then, suddenly, the advance halted. Tacitus offers all kinds of reasons for the delay: the soldiers had to receive additional training, the Cugerni (a tribe inside the empire that had sided with Civilis) had to be punished, they had to fight with enemies for the possession of a heavily-laden corn-ship... The real reason, however, was that news had arrived from the south: by now, Vespasian's legions were invading Italy.

It may be remembered that the army of the Rhine had fought for Nero against Gaius Julius Vindex in 68; nonetheless, Vindex' friend Galba had become emperor, and he had been suspicious of the Rhine army. Flaccus and Vocula wanted to prevent that this history would repeat itself. Suppose that they defeated Civilis, who claimed to fight for Vespasian, and suppose that he defeated Vitellius... This was an unacceptable risk.

In the first days of November, the soldiers received bad news: their emperor Vitellius and his army -which was made up from units from the Rhine- had been defeated. Those at Krefeld personally knew many of the dead. This did little to improve the morale, especially since it was clear that Vitellius could no longer win the civil war. The officers decided that they had to side with Vespasian.

When Hordeonius Flaccus administered the oath of allegiance, the rank-and-file accepted it under pressure from the officers, though with little conviction in their looks or hearts, and while firmly reciting the other formulae of the solemn declaration, hesitated at the name 'Vespasian' or mumbled it, and indeed for the most passed it over in silence. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.31; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

Again, Flaccus and Vocula were forced to wait. They did not know what to do, Julius Civilis had to take the initiative. If he had truly been an adherent of Vespasian, the war was now over, because the legions of the Rhine army had sided with this emperor. If, on the other hand, his use of the letter from Vespasian had been nothing but a masquerade, the war had to continue, and the Romans would have to fight with the bravest of all neighboring tribes. Slowly, the days passed on, and nothing happened. No messengers arrived from the north, and Flaccus understood that the Batavian wanted to continue the struggle.

Civilis knew that he had to destroy the army at Krefeld before it had united with the besieged. He knew that, after the attack on Xanten, the Romans would retaliate, but it would cost half a year before they could sent an army across the Alps -the winter was approaching- and if he had destroyed the army at Krefeld, he could take Xanten and enlarge the rebellious region. He was already negotiating with the Trevirans, who would certainly side with him if the most northerly position of the Roman forces were Mainz, which would fall if the Batavians and Trevirans cooperated. However, Civilis was confronted with one problem: the army of Flaccus and Vocula, even though it consisted of three depleted legions, was too large to face in a regular battle.

Flaccus and Vocula did not have to be clairvoyants to know that the Batavian leader would try to catch them off-guard. And they could also forecast that he would do this on a moonless night, like the night of December 1/2, 69 CE. Tacitus, however, wants us to believe that the attack of the eight Batavian auxiliary units came unexpectedly.

Vocula was unable to address his men or deploy them in line of battle. All he could do when the alarm sounded was to urge them to form a central core of legionaries, around which the auxiliaries were clustered in a ragged array. The cavalry charged, but were brought up short by the disciplined ranks of the enemy and forced back upon their fellows. What followed was a massacre, not a battle. The Nervian auxiliary units, too, were induced by panic or treachery to expose the Roman flanks. Thus the attack penetrated to the legions. They lost their standards, retreated within the rampart, and were already suffering heavy losses there, when fresh help suddenly altered the luck of the battle.

Some Basque auxiliary units [...] had been summoned to the Rhineland. As they neared the camp, they heard the shouts of men fighting. While the enemy's attention was elsewhere, they charged them from the rear and caused a widespread panic out of proportion to their numbers. It was thought that the main army had arrived, either from Neuss or from Mainz. This misconception gave the Romans new heart: confident in the strength of others, they regained their own. The pick of the Batavian fighters -at least so far as the infantry was concerned- lay dead upon the field; the cavalry got away with the standards and prisoners taken in the first phase of the engagement. In this day's work casualties in slain were heavier on our side, but consisted of poorer fighters, whereas the Batavians lost their very best. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.33; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

Again, Tacitus' description is misleading to the extreme. Of course the Basque units did not arrive by accident, as Tacitus seems to imply. They were sent by Flaccus. Likewise, the suggestion that the Nervians 'betrayed' the Romans, is a marvelous example of Tacitean innuendo.

The battle of Krefeld was an important Roman victory, although the losses were severe. This is corroborated by a macabre archaeological discovery: many dead people and horses did not receive a decent cremation, but were hurriedly buried in a large mass grave.

The consequences of the battle were enormous. The eight Batavian auxiliary units now disappear from Tacitus' narrative, although he uses the expression cohortes once in a non-technical sense (at 4.77). Civilis had shown his true intentions and lost his best men, and nothing withheld the Romans from marching on Xanten and lifting the siege.

The camp's walls were strengthened, the ditches deepened, supplies brought in, the wounded taken away. But there was no opportunity to invade the country of the Batavians and retaliate, because bad news arrived from the south: the Usipetes and Chattians, tribes from the east bank of the Rhine, had crossed the river, were plundering the country and tried to besiege Mainz. It did not seem very serious, but it was prudent not to take any risks. After all, Mainz was more important than Xanten.

Therefore, the expeditionary force, strengthened with 1,000 soldiers from Xanten, returned. Immediately, Civilis renewed the siege of an under garrisoned but better equipped Xanten. When his cavalry attacked the retreating army near Neuss, however, they were soundly defeated.

The legionaries had shown their worth at Krefeld and Xanten, and when they reached Neuss, there was a pleasant surprise: Flaccus distributed money to celebrate the accession of Vespasian. As loyal adherents of Vitellius, this was more than the soldiers had expected. These were the days of the Roman carnival, the Saturnalia, and the legionaries celebrated it with pleasure. It must have come as some sort of release after the tensions of the preceding weeks. However, the merrymaking was disturbed.

In a wild riot of pleasure, feasting and seditious gatherings at night, their old enmity for Hordeonius Flaccus revived, and as none of the officers dared to resist a movement which darkness had robbed of its last vestige of restraint, the troops dragged him out of bed and murdered him. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.36; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

The same would have happened to Vocula if he had not been able to make his escape from the camp, dressed as a slave. The assault on the two commanders at the moment when Fortune was smiling at the Romans, is one of the unexplained events during the Batavian revolt.

We can only speculate about the reason. As we have already seen, the Roman expeditionary force had returned to the south and had taken men from Xanten with them. Tacitus mentions that those that were left behind felt themselves betrayed, and understandably so: they were to keep the defeated Batavians occupied while the main force was occupied somewhere else. Is it possible that the murder was not an act of drunken hysteria, but 'fragging', i.e., the killing of a commander who was careless with soldier's lives?

The Gallic Empire

In Italy, the new year 70 CE started with excellent omens. The civil war was over, Vitellius was dead, the new emperor Vespasian turned out to be a kind man, and plans were made to put an end to the Jewish war and the Batavian revolt. The big question was whether the expeditionary force sent across the Alps would be in time to prevent the situation north of Mainz from escalating. As it turned out, the Roman reinforcements arrived too late.

The murder of Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus by his own men, just after he had restored order at Bonn, Cologne, Neuss, and Xanten, had given the defeated rebels new self-confidence. Julius Civilis had renewed the siege of the Fifth legion Alaudae and Fifteenth legion Primigenia at Xanten, and the Trevirans and Lingones, ancient Gallic but romanized tribes living along the Moselle and upper Rhine, decided to revolt, too.

They had seen that the three legions that had temporarily lifted the siege of Xanten (I Germanica, XVI Gallica, XXII Primigenia) were too small to deal effectively with the situation. Of course, the Batavian defeats at Krefeld, Xanten, and Neuss had done something to restore Roman prestige, but the knowledge that Julius Civilis was again besieging Xanten and the obvious division among the Roman legionaries took away the last doubts among the Trevirans and Lingones.

The last Roman success was the relief of Mainz (which was now garrisoned with the Fourth legion Macedonica and the Twenty-second), but when general Gaius Dillius Vocula set out to offer help to the garrison at Xanten, his Treviran and Lingonian auxiliaries deserted. Tacitus introduces the protagonists:

Messages were exchanged between Civilis and Julius Classicus, the commander of the Treviran cavalry regiment. The latter's rank and wealth put him in a class above others. He was descended from a line of kings, and his forebears had been prominent in peace and war. Classicus himself was in the habit of boasting that he counted among his ancestors more enemies of Rome than allies. Also involved were Julius Tutor and Julius Sabinus, the former a Treviran, the latter a Lingon. Tutor had been placed by Vitellius in command of the west bank of the Rhine. Sabinus for his part, naturally a conceited man, was further inflamed by bogus pretensions to high birth. He claimed that the beauty of his great-grandmother had attracted Julius Caesar during the Gallic War and she had become his mistress. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.55; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

The rebellion of Julius Classicus, Julius Tutor and Julius Sabinus has to be distinguished from the revolt of the Batavians. As we will see, the Trevirans and Lingones were fully romanized and wanted to start an empire of their own -the Gallic empire- whereas the Batavians wanted independence of some sort (their war aims are discussed above).

When Vocula saw that Classicus and Tutor persisted in their treachery, he turned round and retired to Neuss. The Gauls encamped three kilometers away on the flat ground. Centurions and soldiers passed to and fro between the camps, selling their souls to the enemy. The upshot was a deed of shame quite without parallel: a Roman army was to swear allegiance to the foreigner, sealing the monstrous bargain with a pledge to murder or imprison its commanders. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.57; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

The former adherents of Vitellius must have found it easy to break their oath to Vespasian. Vocula was killed by a soldier of the First legion Germanica, and Julius Classicus, dressed in the uniform of a Roman general, appeared at the camp and read out the terms of the oath: the legionaries of the First and Sixteenth legions had to uphold the Gallic empire and support its emperor, Julius Sabinus (the fifth emperor in the Roman world in thirteen months). Thereafter, Tutor attacked troops in Cologne and Mainz, and Classicus sent some of the troops that had capitulated to Xanten to offer quarter to its garrison and lure them into surrender. However, the commander of the beleaguered soldiers, Munius Lupercus, refused to come to terms.

After this, the First and Sixteenth were directed to Trier, far away from the theater of war. Their new emperor Sabinus did not fully trust them. Perhaps he should have used them, because his war against the Sequani (who lived along the river Doubs) was unsuccessful.

Sabinus' rashness in forcing an encounter was equaled by the panic which made him abandon it. In order to spread a rumor that he was dead, he set fire to the farmhouse where he had taken refuge, and people thought that he had committed suicide there. [...]

With the Sequanian victory, the war movement in Gaul came to a halt. Gradually the communities began to recover their senses and honor their obligations and treaties. In this the inhabitants of Reims took the lead by issuing invitations to a conference which should decide whether they wanted independence or peace. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.67; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

The result was that the Gauls invited the Trevirans and Lingones to stop their aggression, especially now that the Gallic emperor was (or seemed) dead. However, they refused to do so, and sided with Julius Civilis.

The fall of Xanten

The murder of the Roman general Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus gave new courage to the rebels. The Treviran and Lingonian auxiliary units revolted and Julius Civilis renewed the siege of Xanten. The demoralized legions I Germanica and XVI Gallica surrendered to the Gallic empire of the Trevirans and Lingones. After the disintegration of the Roman army north of Mainz, the two besieged legions at Xanten, V Alaudae and XV Primigenia, were lost. In March 70, their commander Munius Lupercus capitulated.

The besieged were torn between heroism and degradation by the conflicting claims of loyalty and hunger. While they hesitated, all normal and emergency rations gave out. They had by now consumed the mules, horses and other animals which a desperate plight compels men to use as food, however unclean and revolting. Finally they were reduced to tearing up shrubs, roots and the blades of grass growing between the stones - a striking lesson in the meaning of privation and endurance.

But at long last they spoiled their splendid record by a dishonorable conclusion, sending envoys to Civilis to plead for life - not that the request was entertained until they had taken an oath of allegiance to the Gallic empire. Then Civilis, after stipulating that he should dispose of the camp as plunder, appointed overseers to see that the money, sutlers and baggage were left behind, and to marshal the departing garrison as it marched out, destitute. About 8 kilometers from Xanten, the Germans ambushed the unsuspecting column of men. The toughest fighters fell in their tracks, and many others in scattered flight, while the rest made good their retreat to the camp.

It is true that Civilis protested, and loudly blamed the Germans for what he described as a criminal breach of faith. But our sources do not make it clear whether this was mere hypocrisy or whether Civilis was really incapable of restraining his ferocious allies. After plundering the camp, they tossed firebrands into it, and all those who had survived the battle perished in the flames.

After his first military action against the Romans, Civilis had sworn an oath, like the primitive savage he was, to dye his hair red and let it grow until such time as he had annihilated the legions. Now that the vow was fulfilled, he shaved off his long beard. He was also alleged to have handed some of the prisoners over to his small son to serve as targets for the child's arrows and spears. [...]

The legionary commander Munius Lupercus was sent along with other presents to Veleda, an unmarried woman who enjoyed wide influence over the tribe of the Bructeri. The Germans traditionally regard many of the female sex as prophetic, and indeed, by an excess of superstition, as divine. This was a case in point. Veleda's prestige stood high, for she had foretold the German successes and the extermination of the legions. But Lupercus was put to death before he reached her. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.60-61; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

After this success, Julius Civilis and his Treviran ally Julius Classicus moved to Cologne, which lay now unguarded. The city was not plundered, because Civilis owed something to Cologne: his son had been kept alive by its inhabitants when the Romans had demanded his execution. Instead, it became Civilis' headquarters. Coins were minted that commemorated the destruction of V Alaudae and XV Primigenia.

By now, the Batavians were the most important tribe in the north-west of Europe, especially since the emperor of the Gallic empire had disappeared. In the next months, the Batavians would try to subdue the romanized tribes of northern Gaul. Several Germanic tribes from across the Rhine were invited to take a share in the fighting, and gladly responded to the invitation to join the looting of Gallia Belgica.

Julius Civilis had a personal reason for this policy. Claudius Labeo, the former commander of the Batavian cavalry unit that had decided a battle in favor of Civilis but had been rewarded with an exile in Frisia (above), had made his escape. He had been able to reach general Gaius Dillius Vocula, who had helped him to form a small army that attacked the Batavian and Cananefatian homelands from the south. Civilis hated Labeo, and knew that the Batavians at home wanted an end to this guerilla war. The two armies met near the bridge of Trajectum ad Mosam, Maastricht.

Civilis found his advance blocked by the resistance of Claudius Labeo and his irregular body of Baetasii, Tungrians and Nervians. Labeo relied on his position astride a bridge over the river Maas which he had seized in the nick of time. The battle fought in this confined space gave neither side the advantage until the Batavians swam the river and took Labeo in the rear. At the same moment, greatly daring or by prior arrangement, Civilis rode up to the Tungrian lines and exclaimed loudly: 'We have not declared war to allow the Batavians and Trevirans to lord it over their fellow-tribes. We have no such pretensions. Let us be allies. I am coming over to your side, whether you want me as leader or follower.' This made a great impression on the ordinary soldiers and they were in the act of sheathing their swords when two of the Tungrian nobles, Campanus and Juvenalis, offered him the surrender of the tribe as a whole. Labeo got away before he could be rounded up. Civilis took the Baetasii and Nervians into his service too and added them to his own forces. He was now in a strong position, as the communities were demoralized, or else felt tempted to take his side of their own free will. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.66; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

The Latin words that have been translated here as 'in this confined space' (in angustiis), literally mean 'in the mountain passes'. This is nonsense, because the Bemelerberg east of Maastricht is a charming hill, not a mountain. (It is not a confined space either.) However, Tacitus plays a trick. From a Roman point of view, the Batavians were living on the edges of the earth, which consisted of forests and mountains. By mentioning mountain passes, he reminded the reader of the nature of the country, which could, in Roman thought, only produce courageous savages.

After the battle of Maastricht, Julius Civilis moved along the ancient road to Atuatuca, modern Tongeren. Its inhabitants tried to prevent the destruction of their town by building a large wall, but in vain: Tongeren was sacked. After this, the support of the Tungrians, which Civilis had just gained, must have been less enthusiastic.

The empire strikes back

In the Spring of 70 CE, Julius Civilis was at the zenith of his power. Frisians, Cananefates, the Cugerni of Xanten, the Ubians of Cologne, at least some of the Tungrians of Tongeren, and the Nervians all recognized the superiority of the Batavians, and in the south, the Lingones and Trevirans were fighting against Rome as well. However, since Civilis had attacked Xanten, it was certain that the Romans would sent a large army to the north.

Its commander was an old war horse named Quintus Petillius Cerialis, not only a relative of the new emperor Vespasian, but also his companion in the British wars, where he must have met Julius Civilis as well.

The expeditionary force consisted of the victorious Eighth legion Augusta, the Eleventh Claudia and Thirteenth Gemina, the Twenty-first Rapax (which had been one of those supporting Vitellius), and, of the recently recruited legions, the Second Adiutrix. These were led across the Alps by the Great St Bernard and Mont Genevre passes, though part of the army took the Little St Bernard. The Fourteenth legion Gemina was summoned from Britain, and the Sixth Victrix and First Adiutrix from Hispania. [Tacitus, Histories, 4.68; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

Not all these legions saw action. The Eighth merely went from Italy to Strasbourg, where several units may already have been guarding a strategic crossing point of the Rhine. The Eleventh was left behind in Vindonissa (modern Windisch) in Germania Superior. The British and the two Spanish legions first had to pacify parts of Gaul.

So, the army of Cerialis in fact consisted of only three legions, II Adiutrix, XIII Gemina, and XXI Rapax. Nonetheless, it was a powerful army that inspired fear. The army of Civilis' ally Julius Tutor (above) disintegrated even before Cerialis arrived: the former legionaries in Tutor's service returned to their original allegiance, and the soldiers of the two legions that had capitulated, I Germanica and XVI Gallica, did the same. Seeing his enemy collapse in front of him, Cerialis advanced to Mainz, where he found the legions IIII Macedonica and XXII Primigenia (May 70).

The first Roman target was Trier, which dominated an important road from the Mediterranean to the Rhine. Three armies were threatening the capital of the Trevirans: the two legions that had returned to the Roman side; the Sixth legion Victrix and the First Adiutrix from Hispania; and Cerialis' XXI Rapax from the east. Since Julius Civilis was still chasing the guerilla warriors of Claudius Labeo, the Trevirans had to bear the brunt of the battle all alone. They tried to obstruct the latter's advance near a town called Rigodulum (modern Riol), but were decisively defeated. Next day, Cerialis entered Trier. Here, he encountered the legionaries of I Germanica and XVI Gallica. Cerialis was kind towards them, and showed clemency towards the Trevirans and Lingones, punishing only those who were really guilty of treason.

From this moment on, the Romans were not only superior in tactics, discipline, and experience, but also in numbers. However, their armies had not united yet, and this offered an opportunity to Julius Civilis and his allies Julius Tutor and Julius Classicus. They decided to destroy the army at Trier during a nightly surprise attack. It may have been the moonless night of 7/8 June, but this is far from certain. The Romans were indeed surprised and their enemies were able to penetrate the camp, but ultimately the three legions were able to expel the rebels. In fact, this was the decisive battle of the war: from now on, Cerialis could start to reconstruct the Rhine border -the four legions at Mainz may already have made a start- and mop up the last resistance.

News arrived that Cologne had liberated itself. Civilis wanted to suppress this rebellion, but found that the unit of Frisians and Chauci that he wanted to use, was murdered by the inhabitants of Cologne. Even worse, Cerialis' three legions -and perhaps units from the army at Mainz- advanced to the north at top speed. This forced the Batavian leader to return to the north, especially since he knew that the Fourteenth legion Gemina had boarded its ships in Britain and was on its way to the Continent. Civilis was afraid that they might land on the sandy coast of what is now Holland, and hurried back to the Island of the Batavians.

Here, he heard of one of the last successes of his men: the Cananefates had destroyed a part of the Roman navy. However, it was too late: the Fourteenth legion already landed at Boulogne and was marching through Belgica to Cologne.

The theater of war was now narrowed to Germania Inferior on the Lower Rhine, and for the time being, the Romans were content with it. The invasion of the Island of the Batavians, the Betuwe, had no priority. Pacification of the reconquered territories and strengthening the border along the Rhine - these we