The battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE concluded the Second Macedonian War (200-197 BCE) and consolidated Rome's power in the Mediterranean, finally resulting in Greece becoming a province of Rome in 146 BCE. This engagement is sometimes cited as the birth of the Roman Empire in that it proved the superiority of the legions of the Roman army over the Macedonian-Greek phalanx in battle, placed Greece in a subordinate position to Rome, and encouraged further expansion in the region through military conquest which would eventually elevate Rome to the preeminent power in the world of its day.

Significant as Cynoscephalae was, it did not launch the Roman Empire - that came about, at least in part, due to the dynamics in the relationship between three forceful personalities: Octavian (l. 63 BCE - 14 CE, later Augustus Caesar, r. 27 BCE - 14 CE), Mark Antony (l. 83-30 BCE), and Cleopatra VII of Egypt (l. c. 69-30 BCE). The drama which unfolded between these three was concluded at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE which was orchestrated and then capitalized upon by Octavian, enabling him to found the Roman Empire.

Octavian

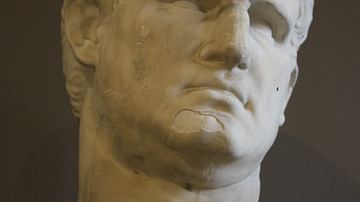

Octavian was born Gaius Octavius Thurinus on 23 September 63 BCE. His father died when he was young, and he was raised, in part, by his grandmother, Julia Minor (l. 101-51 BCE), sister of Julius Caesar. He was kept under her guidance through his teens, even after he had attained the age of maturity at 15.

Octavian was a handsome, studious, and scholarly youth who was indisposed to military life and Roman warfare but, at the same time, was ambitious and intelligent enough to recognize what his culture valued and would reward. In 46 BCE, Julia consented to his request to join his great-uncle on campaign in Hispania. Octavian and a few companions survived a shipwreck, crossed hostile territories, and arrived safely at the Roman camp, which Caesar found most impressive.

In 44 BCE, Octavian was adopted by Caesar as his legitimate heir and was afterwards known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus. When Caesar was assassinated 15 March 44 BCE, Octavian was in Illyria on the Balkan Peninsula engaged in military exercises. He returned to Rome, in spite of suggestions he remain where he was or hide himself from the assassins, where he allied himself with Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (l. 89-12 BCE) to hunt down and punish Caesar's assassins.

Forming themselves into the Second Triumvirate (43-33 BCE) the three would work well together (at least on the surface of things) until the leading assassins Cassius (l. c. 85-42 BCE) and Brutus (l. 85-42 BCE) were defeated in October of 42 BCE at the Battle of Philippi where they took their own lives. Lepidus was given Africa to govern (which effectively removed him from any further power plays) while Antony remained in the east and Octavian returned to Rome.

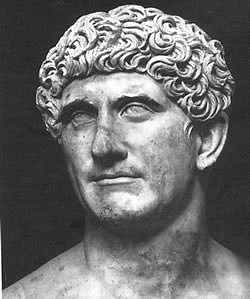

Mark Antony

Julius Caesar's third cousin, once removed, Marcus Antonius was a brilliant general, much loved by his soldiers, and Caesar's best friend. Antony was a rebellious and spendthrift youth but, in his early twenties devoted himself to military training and “quickly showed his aptitude for soldiering, being tough and brave and possessing a gift for leadership” (Everitt, 25). As renowned as he was as a leader of men, he was equally known for his inordinate love of pleasure in the form of wine, women, and gaming. Scholar Anthony Everitt notes:

He much enjoyed having sex with women, a weakness that won him considerable sympathy, writes Plutarch, “for he often helped others in their love affairs and always accepted with good humor the jokes they made about his own.” When he was in funds, he showered money on his friends and was usually generous to soldiers under his command. (25)

He fought alongside Caesar in Gaul, and the two became close friends even though Caesar abstained from drinking and Antony was notorious for drinking with the troops, telling dirty jokes, and encouraging romantic matches for his friends and colleagues. After Caesar's assassination, Antony used the education he had received in Athens on oratory to sway public opinion against Caesar's assassins and then joined with Octavian and Lepidus in hunting down and destroying them.

After Philippi, Antony went to Tarsus in Cilicia where he commanded Cleopatra VII to come to him and answer charges that she had aided and abetted Cassius and Brutus. She met him at the gates of Tarsus, arrayed in Egyptian splendor on her royal barge as it docked on the Cydnus River in 41 BCE, and the two of them soon became lovers. Antony had always set a premium on enjoying himself, especially in the company of women, and, in Cleopatra, he found the perfect companion for these pursuits. Plutarch writes:

Her own beauty, so we are told, was not of that incomparable type that immediately captivates the beholder. But the charm of her presence was irresistible and there was an attraction in her person and in her conversation that, along with a peculiar force of character in her every word and action, laid all who associated with her under her spell… Plato admits four sorts of flattery, but she had a thousand...she played at dice with him, drank with him, hunted with him...at night she would go rambling with him to disturb and torment people at their doors and windows, dressed like a servant woman. (Lives, Antony, Ch. 8)

Cleopatra already had a child by Julius Caesar, Caesarion, and would have three more with Antony – Alexander, Cleopatra Selene II, and Ptolemy. After their meeting at Tarsus, Antony devoted himself to her and would not leave her even when his political career, and even his life, was at stake.

Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII was the daughter of Ptolemy XII Auletes (l. 117-51 BCE) and ruled jointly with him until his death when she was around the age of 18. The Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt, which had ruled since 323 BCE, insisted on a male monarch in keeping with Egypt's tradition and so she was ceremoniously married to her younger brother, Ptolemy XIII (l. 62/61 - 47 BCE) to co-rule but she dropped his name from official documents shortly afterwards and more or less ignored him.

Unlike any of the earlier Ptolemaic monarchs, Cleopatra learned Egyptian as well as a number of other languages so that she was able to communicate with foreign dignitaries and messengers in their own tongue. She was notoriously strong-willed and so difficult for the court advisors to control. In 48 BCE, a coup was orchestrated by her top advisors who placed Ptolemy XIII on the throne, as they thought he would be easier to control, and Cleopatra was driven into exile.

Julius Caesar arrived in Egypt, pursuing his rival Pompey the Great (l. c. 106-48 BCE) in the course of their civil war for the control of Rome. Pompey was assassinated under the direction of Ptolemy XIII, which Caesar is alleged to have strongly objected to, and shortly afterwards Cleopatra had herself smuggled in past Ptolemy XIII's guards to meet the great Roman general.

They became lovers, even though Caesar was married at the time to Calpurnia, and had a son together, Caesarion. Caesar brought them both to Rome in 46 BCE, publicly acknowledging them, and this upset a number of the members of the Roman Senate and the upper class owing to the Roman prohibition of bigamy.

When Caesar was assassinated in 44 BCE, Cleopatra fled with Caesarion back to Egypt which is where she was when Antony summoned her to Tarsus in 41 BCE. Cleopatra had actually met Antony years before when she was a young girl of 14 and Antony was said to have been attracted to her but, when she met him in 41 BCE, the attraction was mutual. The two of them quickly became inseparable but, while their love affair was developing, Octavian was bearing the brunt of taking care of the affairs of Rome.

Tensions & War

The son of Pompey the Great, Sextus Pompey (l. 67-35 BCE), had continued to fight against Caesar's forces even after his father had been killed in 48 BCE. He controlled Sicily and operated a fleet of pirate ships, which harried Roman merchants. In 41 BCE, Octavian launched a campaign against Sextus, who was supported by Antony simply because Antony would support anyone who opposed Octavian and, further, Octavian had recently put down a rebellion by Antony's younger brother. Octavian and Antony met and agreed on a peace between them which included Antony marrying Octavian's sister Octavia.

Without Antony's support, Sextus was fair game for Octavian who, with the assistance of his great general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (l. 64-12 BCE) and Lepidus, destroyed Sextus' fleet and killed him in 35 BCE. Lepidus then claimed Sicily and Sextus' goods as his own which displeased Octavian who exiled him from the Second Triumvirate and sent him back to his regions of Africa.

Antony, meanwhile, had attempted to elevate his stature with an invasion of Parthia which failed on a grand scale, costing him 30,000 men, and then was also defeated in an attempt at taking Armenia. Octavian, at the same time, had elevated his status by resolving the piracy issue in killing Sextus and also securing the frontiers of northeast Italy in a series of stunning campaigns.

In 33 BCE, the legal tenure of the Second Triumvirate was up and Antony sent word to the Senate that he did not wish to be nominated again. He had already repudiated Octavia when she arrived at his palace and had married Cleopatra. When Octavian objected, Antony wrote him:

What has upset you? Because I go to bed with Cleopatra? But she is my wife, and I've been doing so for nine years, not just recently. And, anyway, is [your wife] your only pleasure? I expect that you will have managed, by the time you read this, to have hopped into bed with [many different women]. Does it really matter where, or with what women, you get your excitement? (Lewis, 133)

Octavian found Antony's humiliation of Octavia and association with Cleopatra intolerable, but then Antony declared Caesarion the true heir to Caesar's legacy and, further, bequeathed a number of regions he held – or presumed he held – to his children with Cleopatra – Alexander, Cleopatra, and Ptolemy. Octavian understood he needed to destroy Antony but could not because Antony was still so popular in Rome.

Octavian's Propaganda Campaign

To destroy Antony, Octavian understood, he would need to first undermine his support and, to do that, he struck at Cleopatra – not through military might but through words. Octavian was informed that Antony's will was kept in the temple of the goddess Vesta, which was tended by the Vestal Virgins. Octavian arrived there and demanded they surrender the will, which they refused to do but gave him leave to take it if he wanted as there was really very little they could do to stop him.

Octavian read the will to the Senate and Assembly, pointing out that Antony planned to leave a sizeable inheritance – which by rights belonged to the people of Rome – to a bastard son whom Cleopatra claimed was Caesar's and the three children Antony and Cleopatra had together. He further encouraged the belief that Cleopatra had seduced Antony through charms and spells, bewitching him, and had him under her control – through supernatural means – just as she had done earlier with Caesar. Octavian's plan worked and the people – and Senate – blamed Cleopatra for all of Antony's recent failings. The Senate then declared war on Cleopatra which Octavian's propaganda spun as a mission to save Antony from her enchantment.

The Battle of Actium

Confident that Antony would not abandon Cleopatra, Octavian drove his propaganda forward and, of course, he was right. Antony mobilized his armies, with Cleopatra's support, and established a position at Actium, Greece on the coast of the Ionian Sea. He understood that he could not march on Octavian in Italy with Cleopatra by his side because her reputation had been so completely destroyed by Octavian that he would find no support at home. He also could not march on Rome without Cleopatra because he needed her for both moral and financial support. He had to make Octavian come to meet him in battle and Octavian did just that.

Long before Antony expected his arrival, Octavian came with Agrippa and destroyed Antony's supply lines – which were coming up from Egypt - along the Peloponnese. Octavian then encamped his land forces five miles north of Antony and Cleopatra's site while Agrippa held the sea, preventing any escape. Antony understood his situation was dire and had the war chests loaded onto Cleopatra's flagship, and the sails of his warships kept ready to be unfurled in case the battle went against him. He agreed with Cleopatra that, if Octavian seemed to be gaining the upper hand, they would break through the lines of Agrippa's fleet and escape back to Egypt.

At around noon on 2 September 31 BCE, the ships of Mark Antony and Cleopatra met the fleet of Agrippa under Octavian's supervision outside the Gulf of Actium in Greece. Antony's ships were Roman quinqueremes which were the largest and best equipped of those used in Roman naval warfare. His ships, however, were seriously undermanned due to a malaria outbreak which had struck his crews and, further, were difficult to maneuver quickly.

Octavian's ships, on the other hand, were the smaller vessels known as Liburnian ships, usually employed for patrols, which were easy to maneuver, equipped with ramming devices at the prow, and fully manned with healthy crews. A further blow against Antony's hopes for success was the defection of one of his generals, Quintus Dellius, to Octavian's side with all of Antony's battle plans. Antony also hinged his hopes on the belief that the wind would aid him in turning Agrippa's fleet southward which would give Antony an advantage.

Sometime after midday, on the 2nd of September, the two fleets met in battle on the sea. It was apparent, shortly, that the battle was not going well for Antony primarily because of Agrippa's superior tactics and his use of the weapon known as the harpax – a wooden beam encased in iron with a hook at one end and rope at the other attached to a windlass aboard a ship. The harpax would be fired from a catapult, strike the enemy ship, and then be reeled in by the windlass, securing the opposing ship for boarding. Antony's own flagship was secured by a harpax and the sea battle soon took on the form of a land battle with Antony's ships stalled in the water while Agrippa's crews boarded and attacked.

As it became increasingly apparent that Antony was going to lose the engagement, his ships began to surrender, either returning to the harbor or raising their oars as a signal. As per their agreement, Cleopatra, with her 60 ships, raised sail and left the battle for the open sea. Antony left his flagship, which was hopelessly overwhelmed, by jumping to another and followed Cleopatra with 40 of his own ships, leaving some 5,000 men and 300 ships to be destroyed by Octavian.

Conclusion

Once they were back in Egypt, Cleopatra tried to rally Antony to pursue other measures against Octavian. She suggested they flee to Spain where they could capture the silver mines to pay for an army and begin life again by setting up a new and even more powerful kingdom elsewhere. Antony, crushed by his defeat at Actium, had no interest in her plans and preferred to drink and neglect his responsibilities. He only returned to a semblance of his former greatness when Octavian arrived in Egypt in July of 30 BCE. Antony led his army against the advance troops of Octavian's army, scattering them, but a day later most of his troops had defected, realizing there was no future for them in continuing to follow Antony.

After hearing about his troops' defection, Antony was told that Cleopatra had died. He stabbed himself, asking only that he be brought to wherever her body had been placed. Cleopatra still lived, however, secure in a citadel in Alexandria, and Antony lived long enough to die in her arms. Octavian took the city without effort and presented Cleopatra with his terms – which included her transport to Rome as a captive to be paraded in a Roman triumph. Cleopatra requested time to prepare herself, which was granted, and then killed herself to deprive Octavian of his prize.

Octavian had Antony and Cleopatra buried together, in accordance with their wishes, and then had Caesarion strangled. Antony and Cleopatra's three children were taken to Rome where they appeared in Octavian's triumphal procession marching behind an effigy of their mother. Octavian was heralded as the savior of Rome who had delivered the people from eastern domination but, keenly attuned to how fickle the mob can be, he was careful to present himself as their humble servant who had only done what was required of him as his duty. In 27 BCE, he declared the time of crisis had passed and surrendered his power, which was hastily restored to him by the grateful Senate of Rome along with the title Augustus – and the Roman Empire was born.