The Cycladic islands of the Aegean were first inhabited by voyagers from Asia Minor around 3000 BCE and a certain prosperity was achieved thanks to the wealth of natural resources on the islands such as gold, silver, copper, obsidian and marble. This prosperity allowed for a flourishing of the arts and the uniqueness of Cycladic art is perhaps best illustrated by their clean-lined and minimalistic sculpture which is amongst the most distinctive art produced throughout the Bronze Age Aegean. These figurines were produced from 3000 BCE until around 2000 BCE when the islands became increasingly influenced by the Minoan civilization based on Crete.

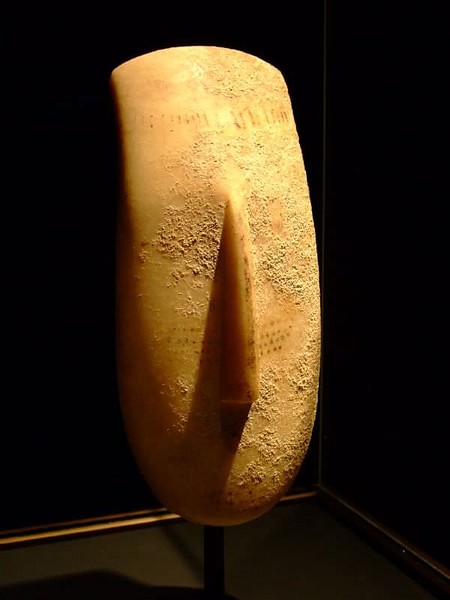

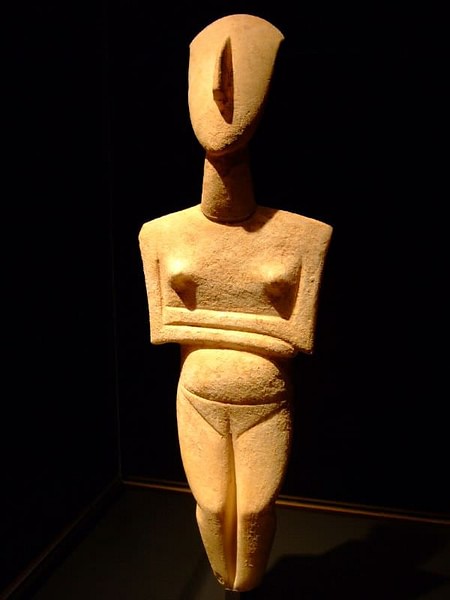

Small statuettes were sculpted from local coarse-grained marble and although different forms were produced, all share the same characteristics of being highly stylized with only the most general and prominent body features represented. The earliest examples were produced in the Neolithic period and were made until around 2500 BCE. Looking like violins they are in fact representations of a naked squatting woman. A later form, and perhaps influenced by contact with Asia, was the standing figure, most commonly female. Once again, these elegant figures are highly stylized with few details added and they continued to be produced until around 2000 BCE. They are naked, with arms folded across the chest (always with the right arm under the left) and the oval-shaped head tilted back with the only sculpted feature being the nose. Breasts, pubic area, fingers and toes are the only other features evidenced by simple inscribed lines. Over time the figures evolve slightly with a deeper line incised to demarcate the legs, the top of the head becomes more curved, knees are less bent, shoulders more angular and the arms are less fully crossed. The figures are most often around 30cm in height but miniature examples survive, as do life-size versions. The feet of the figures always point downwards and therefore they cannot stand upright on their own, leading to suggestions that they were either laid down or carried. Despite these general similarities it is, however, important to note that no two figurines are exactly alike, even when evidence suggests they come from the same workshop.

Other figures include harp players seated on a throne or, more usually, a simple stool (of which there are fewer than a dozen surviving examples) and a standing pipe or aulos player from Keros c. 2500 BC. In the same style as other Cycladic figures they are the first representations of musicians in sculpture from the Aegean.

Most of the figures were sculpted from slim rectangular pieces of marble using an abrasive such as emery which is almost as hard as diamond and was available from the island of Naxos. Without doubt an extremely laborious process was involved but the end result was a piece with a finely polished sheen. There are on occasion surviving traces of colour on some statues which was used to highlight details such as hair in red and black and facial features were also painted onto the sculpture such as eyes. Representations of the mouth, however, are very rare on Cycladic sculpture. A well-preserved figure now in the British Museum still has traces of eyes, a necklace and a diadem painted with small dots on the face and there are even some patterns over the body, hinting at a more colourful representation than most surviving figures suggest.

Not only have figures been found all over the Cycladic islands but they were clearly also popular further afield on Crete, the Greek mainland and at Cnidus and Miletus in Anatolia. Both imported figurines and local copies have been discovered, some of the latter employing material not used by the original manufacturers such as ivory.

The use of such a hard material and consequently the time needed to produce these pieces would suggest that they were of great significance in Cycladic culture (and not mere toys as some have suggested) but their exact purpose is unknown. Their most likely function is as some sort of religious idol and the predominance of female figures, sometimes pregnant, suggests a fertility deity. Supporting this view is the fact that figurines have been found outside of a burial context at settlements on Melos, Kea and Thera. Alternatively, precisely because the majority of figures have been found in graves, perhaps they were guardians to or representations of the deceased. Indeed, there have been some finds of painting materials along with figures in graves which would suggest that the painting process may have been a part of the burial ceremony. However, some of the larger figures are simply too large to fit into a grave and also puzzling is their variation in distribution. Although figurines are present across the Cycladic islands, some graves have contained as many as fourteen figures whilst on Syros for example, only six were found in 540 graves. Intriguingly, at the site of Dhaskalio Kavos on Keros there is evidence of a large quantity of figures deliberately broken. Were these smashed as part of a ritual or were they simply no longer seen as significant objects?

Despite much scholarly endeavour then, there is still great mystery surrounding these statues and perhaps this is part of their appeal. One of the problems with Cycladic art is that it is very much a victim of its own success. Appreciated by artists such as Pablo Picasso and Henry Moore in the 20th century CE, a vogue for anything Cycladic arose which unfortunately resulted in the illegal traffic of looted goods from the Cyclades. The result is that many of the Cycladic art objects now in western museums have no provenance of any description, compounding the difficulties for scholars to ascertain their function in Cycladic culture. These objects are, nevertheless, part of the few tangible remains of a culture which no longer exists and without a form of writing the members of that culture are unable to explain for themselves the true significance of these objects and we are left to imagine the function and faces behind these enigmatic sculptures which continue to fascinate more than three millennia after their original manufacture.