If there was one thing the Roman people loved it was spectacle and the opportunity of escapism offered by weird and wonderful public shows which assaulted the senses and ratcheted up the emotions. Roman rulers knew this well and so to increase their popularity and prestige with the people they put on lavish and spectacular shows in purpose-built venues across the empire. Such famous venues as the Colosseum and Circus Maximus of Rome would host events involving magnificent processions, exotic animals, gladiator battles, chariot races, executions and even mock naval battles.

Venues

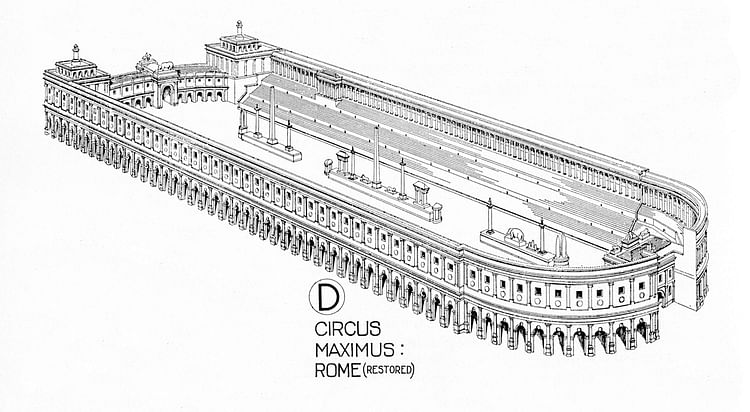

It is significant that most of the best-preserved buildings from the Roman period are those which were dedicated to entertainment. Amphitheatres and circuses were built across the empire and even army camps had their own arena. The largest amphitheatre was the Colosseum with a capacity of at least 50,000 (likely more, if one factors in the smaller bodies and different sense of personal space compared to modern standards) whilst the Circus Maximus could hold a massive 250,000 spectators according to Pliny the Elder. With so many events on such a large scale, spectacles became a huge source of employment, from horse trainers to animal trappers, musicians to sand rakers.

From the end of the republic seats in the theatre, arena and circus were divided by class. Augustus established further rules so that slaves and free persons, children and adults, rich and poor, soldiers and civilians, single and married men were all seated separately, as were men from women. Naturally, the front row and more comfortable seats were reserved for the local senatorial class. Tickets were probably free to most forms of spectacle as organisers, whether city magistrates given the responsibility of providing public civic events, super-rich citizens or the emperors who would later monopolise control of spectacles, were all keen to display their generosity rather than use the events as a source of revenue.

Chariot Races

The most prestigious chariot races were held in Rome's Circus Maximus but by the 3rd century CE other major cities such as Antioch, Alexandria and Constantinople also had circuses with which to host these spectacular events, which became, if anything, even more popular in the later empire. Races at the Circus Maximus probably involved a maximum of twelve chariots organised into four factions or racing-stables - Blues, Greens, Reds, and Whites - which people followed with a passion similar to sports fans today. There was even the familiar hatred of opposing teams as indicated by lead curse tablets written against specific charioteers and certainly bets, both large and small, were placed on the races.

Different types of chariot races could require more technical skill from the charioteers, such as races with teams of six or seven horses or using unyoked horses. Nero even raced with a ten-horse team but came a cropper as a result and was thrown from his chariot. There were races where charioteers raced in teams and the most anticipated races of all, those only for champions. Successful racers could become millionaires and one of the most famous was Gaius Appuleius Diocles who won an astonishing 1463 races in the 2nd century CE.

In the imperial period the circus also became the most likely place for a Roman to come into contact with their emperor and, therefore, rulers were not slow to use the occasions to strengthen their emotional and political grip on the people by putting on an unforgettable show.

Gladiator Contests

Just as modern cinema audiences hope to escape the ordinariness of daily life, so too the crowd in the arena could witness weird, spectacular, and often bloody shows and become immersed, even lost, in the seemingly uncontrollable emotion of the arena. Qualities such as courage, fear, technical skill, celebrity, the past revisited, and, of course, life and death itself, engaged audiences like no other entertainment and no doubt one of the great appeals of gladiator events, as with modern professional sport, was the potential for upsets and underdogs to win the day.

The earliest gladiator contests (munera) date to the 4th century BCE around Paestum in southern Italy whilst the first in Rome itself are traditionally dated to 264 BCE, put on to honour the funeral of one Lucius Junius Brutus Pera. Eventually, arenas spread around the empire from Antioch to Gaul as rulers became ever more willing to show off their wealth and concern for the public's pleasure, In Rome city magistrates had to put on a gladiator show as the price for winning office and cities across the empire offered to host local contests to show their solidarity with the ways of Rome and to celebrate notable events such as an imperial visit or an emperor's birthday.

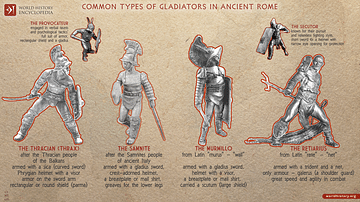

In the 1st century BCE schools were established to train professional gladiators, especially in Capua (70 BCE), and amphitheatres were also made into more permanent and imposing structures using stone. The events became so popular and grandiose that limits were put on just how many fighting pairs would participate in a show and how much money was allowed to be poured into them. Due to this expense and the additional hazard of fines for hiring a gladiator and not returning him in good condition, many gladiator contests now became less fatal for the participants and this strategy also served to add more drama to the public execution events where death was absolutely certain.

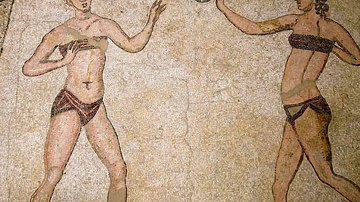

There were slave gladiators as well as freed men and professionals, and for extra special occasions even female gladiators, fighting each other. Some gladiators became heroes, especially the champions or primus palus, and the darlings of the crowd; some even had their own fan clubs. Gladiators seem also to have been considered a good financial investment as even such famous figures as Julius Caesar and Cicero owned significant numbers of them, which they rented out to those who wished to sponsor a gladiator games.

Some elite writers such as Plutarch and Dio Chrysostom protested that the gladiator contests were unbecoming and contrary to 'classical' cultural ideals. Even some emperors displayed little enthusiasm for the arena, the most famous case being Marcus Aurelius, who took his paperwork to the events. Whatever their personal tastes though, the shows were too popular to be stopped and it was only in later times that gladiator contests, at odds with the new Christian-minded Empire, declined under the Christian emperors and finally came to an end in 404 CE.

Wild Animal Hunts

Besides gladiator contests, Roman arenas also hosted events using exotic animals (venationes) captured from far-flung parts of the empire. Animals could be made to fight each other or fight with humans. Animals were frequently chained together, often a duo of carnivore and herbivore and cajoled into fighting each other by the animal handlers (bestiarii) Certain animals acquired names and gained fame in their own right. Famous 'hunters' (venatores) included the emperors Commodus and Caracalla, although the risk to their person was no doubt minimal. The fact that such animals as panthers, lions, rhinos, hippopotamuses, and giraffes had never been seen before only added to the prestige of the organisers of these shows from another world.

Triumphs, Processions & Naval Battles

Triumphs celebrated military victories and usually involved a military parade through Rome which began at the Porta Triumphalis and, via a convoluted route, ended at the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitol. The victorious general and a select group of his troops were accompanied by flag bearers, trumpeters, torch bearers, musicians and all of the magistrates and senators. The general or emperor, dressed as Jupiter, rode a four-horse chariot accompanied by a slave who held over his master's head a laurel wreath of victory and who whispered in his ear not to get carried away and allow his pride to result in a fall. During the procession captives, booty and the flora and fauna from the conquered territory were displayed to the general populace and the whole thing ended with the execution of the captured enemy leader. One of the most lavish was the triumph to celebrate Vespasian and Titus' victory over Judaea in which the spoils from Jerusalem were shown off and the whole event was commemorated in the triumphal arch of Titus, still standing in the Roman Forum. Although the emperors would claim a monopoly on the event, Orosius informs us that by the time of Vespasian, Rome had witnessed 320 triumphs.

Triumphs and lesser processions such as the ovatio were often accompanied by gladiator, sporting, and theatre events and quite often ambitious building projects too. Julius Caesar commemorated the Alexandrian war by staging a huge mock naval battle (naumachiae) between Egyptian and Phoenician ships with the action taking place in a huge purpose-built basin. Augustus actually staged a mock battle at sea to celebrate victory over Mark Anthony and another huge staged battle in another artificial pool to reenact the famous Greek naval battle at Salamis. Nero went one better and flooded an entire amphitheatre to host his naval battle show. These events became so popular emperors such as Titus and Domitian did not need the excuse of a military victory to wow the public with epic mythologically-themed sea battles. The manoeuvres and choreography of these events was invented but the fighting was real and so condemned prisoners and prisoners of war gave their lives to achieve ultimate realism.

Theatre

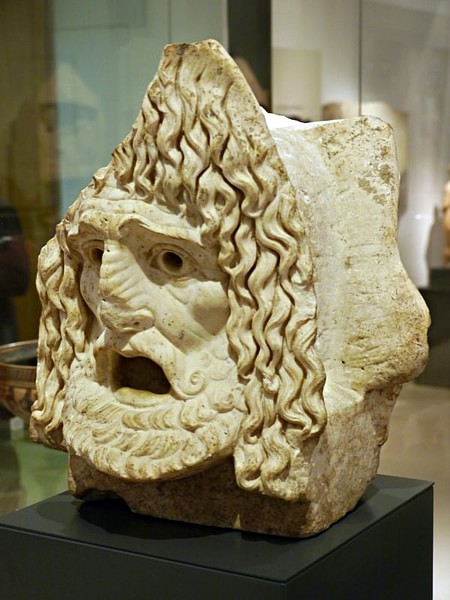

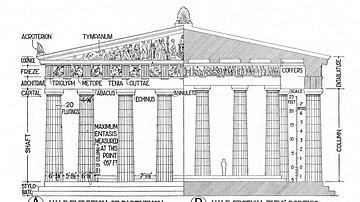

Drama, re-enactments, recitals, mime, pantomime, tragedy and comedy (especially the Classical Greek plays) were held in purpose-built theatres, with some, such as Pompey's in Rome, boasting a capacity of 10,000 spectators. There were also productions of the most famous scenes from classic productions and Roman theatre, in general, owed much to the conventions established by earlier Greek tragedy and comedy. Important Roman additions to the established format included the use of more speaking actors and a much more elaborate stage background. Theatre was popular throughout the Roman period and the rich sponsored productions for the same reasons they patronised other spectacles. The most popular theatre format was pantomime where the actor performed and danced to a simple musical accompaniment which was inspired by classic theatre or was entirely new material. These solo performers, who included women, became theatre superstars. Indeed, in a sense great star performers like Bathyllus, Pylades and Apolaustus became immortal as successive generations of actors would take on their names.

Public Executions

Execution of criminals could be achieved by setting wild animals on the condemned (damnatio ad bestias) or making them fight well-armed and well-trained gladiators or even each other. Other more theatrical methods included burning at the stake or crucifixion, often with the prisoner dressed up as a character from Roman mythology. The crime of the condemned was announced before execution and in a sense the crowd became an active part of the sentence. Indeed, the execution could even be cancelled if the crowd demanded it.

Conclusion

The intellectual elite's lack of interest in spectacle has resulted in few systematic literary references to it and their dismissive attitude is summed up in Pliny's comment on the popularity of chariot teams in the circus - 'how much popularity and clout there is in one worthless tunic!'. However, the myriad of side references to spectacle in Roman literature and surviving evidence such as architecture and depictions in art are testimony to the popularity and longevity of the events mentioned above.

To modern eyes the bloody spectacles put on by the Romans can often cause revulsion and disgust but perhaps we should consider that the sometimes shocking events of Roman public spectacles were a form of escapism rather than representative of social norms and barometers of accepted behaviour in the Roman world. After all, one wonders what type of society a visitor to the modern world might envisage by merely examining the unreal and often violent worlds of cinema and computer games. Perhaps the shockingly different world of Roman spectacle in fact helped reinforce social norms rather than acted as a subversion of them.