Christianity is the world's largest religion, with 2.8 billion adherents. It is categorized as one of the three Abrahamic or monotheistic religions of the Western tradition along with Judaism and Islam. 'Christian' is derived from the Greek christos for the Hebrew messiah ("anointed one"). Christianoi, "followers of the Christ," became the name of a group who followed the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth in 1st-century Israel and proclaimed him the predicted messiah of the prophets.

Christianity merged the beliefs of ancient Judaism with elements from the dominant culture of the Roman Empire. The sacred texts are combined in the Christian Bible: the Jewish Scriptures (now deemed the Old Testament) and the New Testament (the gospels, the letters of Paul, and the Book of Revelation). This article surveys the origins of the movement that ultimately became an independent religion.

Background in Ancient Judaism

Ancient Judaism shared many elements with other cultures and their religious views. They believed that the heavens contained gradients of divine powers that directly affected their daily lives. What distinguished ancient Jews from their neighbors was the command of their God of Israel to make sacrifices (offerings) to him only; 'worship' in this sense meant sacrifices. Jews had distinct ethnic identity markers: circumcision, dietary laws, and the observance of the Sabbath (suspension of all work every seventh day). An ancient leader, Moses, was believed to have received a law code directly from God to organize the Jews as a nation under the Law of Moses. They established a kingdom in Canaan under the auspices of King David and Solomon, who built the Temple in Jerusalem (1000-920 BCE).

The Jews suffered several national disasters over the centuries. The Assyrian Empire conquered and destroyed the Northern Kingdom of Israel in 722 BCE, which was followed by the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 587 BCE. The prophets of Israel (oracles) rationalized the disasters by claiming that God had punished the Jews because of their integration of idolatry in the land. However, they offered a message of hope; in the future, God would intervene one more time in human history in the final days. At that time, God would raise up a messiah from the lineage of King David, and some Gentiles (non-Jews) would then turn and worship the God of Israel. There would be a final battle against the nations, and Israel would be restored to its former glory. Israel would serve as a model righteous nation for the rest of the world, elevating their God above all others.

Greek & Roman Occupations

In the 1st century BCE, the Jews were ruled by the Seleucid Empire. King Antiochus Epiphanes (r. 175-164 BCE) forbid Jewish customs and ordered Jews to sacrifice to the gods of the Greek religion. The Jews, under the leadership of a Hasmonean family, rose up in the Maccabean Revolt and drove them out. As recorded in 2 Maccabees, their sufferings introduced two new concepts into Judaism:

- the concept of a martyr ("witness") as someone who died for their beliefs

- all martyrs would be rewarded with instantly being resurrected to heaven

Rome conquered Judea in 63 BCE. Various Jewish sects, such as the Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, and Zealots, responded to the occupation in different ways. These groups shared the basic traditions but differed in how to respond to the new oppressor and the dominant culture of the Roman Empire.

During the 1st century CE, many messianic contenders attempted to foster rebellion among the crowds at festivals times. Rome's typical response was killing the leader and as many followers as they could find. Advocating a kingdom that was not Rome was equivalent to treason, for which the punishment was crucifixion.

Jesus of Nazareth

An itinerant preacher from Nazareth, Jesus, became the focus of a sect of Jews who had gathered to listen to his sermons in the Galilee region. In line with the prophets of Israel, he declared that the kingdom was imminent; God would shortly intervene and provide justice for all. He selected twelve disciples (students) as a symbol of the twelve tribes of Israel. According to the gospels (stories of Jesus written between 70-100 CE), he became famous for his miracles. His followers declared him the promised messiah.

The gospels reported that on a trip to Jerusalem during Passover (c. 30-33 CE) Jesus was put on trial by the Sanhedrin (the ruling council in Jerusalem) for allegedly preaching against the Temple practices. Condemned, he was handed over to the Roman procurator, Pontius Pilate, who crucified him for the claim that he was the King of the Jews. The trial and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth eventually became part of Christian liturgy (church rituals) by reenacting these events every year, during Easter Week.

This sect of Jews differed from the others in their messianic claims for Jesus; despite having been killed, he was resurrected from the dead on the Sunday following his death. According to Luke, he bodily ascended to heaven. What made this sect of Jews different from others was their teaching that those who followed Jesus would also share in the resurrection of the dead.

The gospel writers also had to face the problem that when Jesus was on earth, the kingdom had not been realized. An early follower conceived of the idea known as the parousia ("second appearance"), according to which Jesus would return to earth sometime in the future, and then all the predictions of the prophets would be fulfilled. Modern Christians still anticipate the return of Christ.

The Gentile Missions

According to the Acts of the Apostles 2, on the Jewish feast of Pentecost, the Holy Spirit came upon the disciples and imbued them with the power to take the message of Jesus to other cities as missionaries. The ritual of admission was baptism, a water ritual that symbolized that one had repented and turned to God. This was initially begun by a contemporary of Jesus, a man known as John the Baptist.

When the first Christian missionaries took their message to other cities, to their surprise, more Gentiles wanted to join the movement than Jews. A meeting was held in Jerusalem (c. 49 CE) to decide whether these Gentiles had to convert to Judaism first. The Apostolic Council decided that the Gentiles did not have to adopt the ethnic identity markers of Jews (circumcision, dietary laws, Sabbath), but they did have to cease eating meat found in the wild, food sacrificed to idols, and follow Jewish incest codes.

Paul the Apostle

As a Pharisee, Paul initially opposed the new movement. He then received a vision of Jesus (now termed 'Christ') who told him that he was to be his apostle ("herald") to the Gentiles. Paul traveled to the eastern cities of the Roman Empire, preaching whatever traditions he knew concerning Christ, but adding the complete abolition of idolatry itself for his members. For thousands of years, ancient cultures had envisioned religious ideas as being in the blood, passed down through the ancestors who had received them from the gods. Paul upended this ancient system, by claiming that faith (pistis, "loyalty") to the teachings of Christ was all that was necessary for salvation (soter, "to be saved"). The letters of Paul the Apostle to the Gentiles indicate that he was often arrested and jailed for such teaching.

Paul said that Adam's sin brought the punishment of death into the world and Christ's death brought eternal life. Christ atoned for the sin of Adam, 'covering over,' 'restoring the violation of sin'. Applying analogies from the courts, Paul taught that followers were acquitted ("righteoused") from having to undergo the punishment for sin, that of death. The later Church Father, Augustine of Hippo (354-430) claimed that the original sin of Adam and Eve left a stain on the first human through sexual intercourse, which was then passed on to all humans. This introduced the Christian concept of human sexuality as sin and also led to the conviction that no one could be saved without baptism.

Paul said that when Christ returns, believers will be transformed into spiritual bodies and join Christ in leading God's kingdom on earth. As the decades passed and Christ did not return, this became adjusted to the conviction that even though believers still physically die, they would be able to share in the afterlife in heaven.

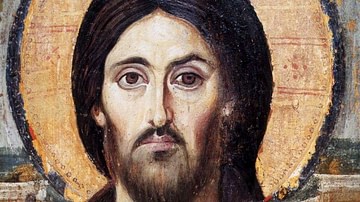

Christ as God

A major innovation in relation to Judaism was Paul's preaching (Philippians 2) that Christ was present at the creation and had descended from heaven as a manifestation of God himself in a human body. As such, Christ was now worthy of worship, with the title of "Lord" and equivalent to God. For Gentiles, this idea fitted well with their stories of their own gods traveling to earth in disguise, but for many Jews, this teaching was offensive and blasphemous.

The Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Roman general and future Roman emperor Titus in 70 CE. This event became a Christian rallying cry against the Jews who did not accept Jesus as the messiah; God had punished them by utilizing Rome to destroy their system of belief.

The innovative teachings of Early Christianity were perhaps the major incentives for the spread of the movement throughout the Empire. No longer tied to geography or ethnic ancestors, believers were embraced from all provinces and all classes into a collective of shared religious concepts. By the 2nd century CE, Christians could be found from Britain (and mainland Europe) to Africa and areas of Asia.

The Persecution of Christians (90-312 CE)

Ancient Rome had collegia, groups of people who shared the same business or trade and met together under the auspices of a deity. However, the group had to have permission to meet from the Roman Senate, a license for assembly. Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) granted Jews the right to assemble and exempted them from the state cults of Rome, but Christians did not have the same right because they were not Jews (not circumcised).

Based upon the Greek concept of apotheosis ("to deify"), Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) instituted the imperial cult, and beginning with Julius Caesar, dead emperors were understood to be with the gods. It evolved into the elevation of living emperors as responsible for the dictates of the gods and was utilized as propaganda throughout the Roman Empire. Christians refused to participate, and Rome's response to the spread of Christianity was charging them with the crime of atheism, "disrespect for the gods." Angering the gods threatened the prosperity of the Roman Empire, and so it was the equivalent of treason. This was the reason that Christians were executed in the arenas, with the phrase "Christians to the lions." For the next 300 years, Christian leaders continually petitioned emperors to grant them the same exemption from state cults as the Jews but were refused until 313 CE.

Christians adopted the same concept as the Maccabees by claiming that anyone who died for their faith was instantly transferred to the presence of God as a martyr. Martyrdom absolved all sins, and later, legendary literature known as martyrology described the details of their ordeals. However, the persecution was sporadic and limited to times of crisis. Earthquakes, plagues, inflation, famine, drought, and invasions on the borders assumed that the gods were angry, and Christians became a convenient scapegoat for such disasters. The most severe persecutions took place during the reign of Decius (251 CE) and Diocletian (302/303 CE).

The Creation of the Church & Institutional Hierarchy

By the middle of the 2nd century, decades had passed and the kingdom of God had not arrived. Christians still believed in the return of Christ, but this was now put off to the future. In the interim, Christian assemblies became institutionalized in the election of leaders and organized with the idea that believers should live as if the kingdom were already here; the kingdom would be found in the Church. (The Greek ecclesia, "assembly," ultimately was translated as "church"). Very few Jewish-Christians remained in the Christian communities. Christian leaders were educated converts from the dominant culture.

Retrospectively deemed Church Fathers, the writings and views of these men became Christian dogma, an accepted set of beliefs for the group:

- The election of clergy – Borrowing an administrative level from the provincial Roman government, bishops (overseers in a diocese) were elected by the communities. Deacons were also elected to help serve bishops in the distribution of charity. Deacons eventually became priests, and together, the two levels constituted Christian clergy.

- The Spirit of God – The spirit of God had imbued Christ with the ability to forgive sins on earth. It was understood to have been granted first to his disciple, Peter, and then to the others. They passed the spirit to the elders they appointed, and the Christian clergy was granted the unique power to forgive sins on earth.

- Christian philosophy – Philosophers shared a common belief in the existence of a higher god, an ethereal first being who emanated the various powers in the universe. God then emanated a concept known as logos (often translated as "word") to organize matter in the universe. Christian writers claimed the higher god was the God of Israel, who emanated Christ in the form of the logos.

- Celibacy for the clergy – Applying analogies of athletic discipline, ascesis, asceticism (not indulging the body) became an important Christian ideal. Christian clergy were urged to remain celibate (no marriage) and chaste (no intercourse), which elevated them above the community as living martyrs who sacrificed a normal life for the sake of the Church.

- Orthodoxy/Heresy – Another major innovation emerged in the twin concepts of orthodoxy ("correct belief") and heresy (from the Greek haeresis, a school of philosophy). In the middle of the 2nd century CE, Christian communities categorized under the umbrella term 'Gnostics' emerged. Gnostics claimed to have secret knowledge about the nature of God, the universe, and Christ. Their ideas challenged mainstream Christian teaching on the salvation found in the crucifixion and the resurrection of the body. The reaction against the Gnostics was the production of an enormous body of literature, outlining correct beliefs (orthodoxy) as opposed to the incorrect beliefs of these groups (heresy). These teachings became the later basis for the Christian Creeds. Declaring the Gnostic gospels heretical saw the beginning of the eventual canonization of only four gospels in the New Testament: Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John.

- The separation of Christianity from Judaism – In 135 CE, the Jews revolted against Rome, and when the Bar-Kokhba Revolt failed, Christian leaders were anxious to convince Rome that Christians were patriotic citizens who obeyed the Roman law. In their appeals to stop Christian persecution, Christian leaders petitioned emperors to recognize the antiquity of Christians, as verus Israel, the true Jews of God's original covenant. To prove the antiquity of Christians, the philosophical literary device of allegory was applied to the Jewish Scriptures. The testament of the Jews and the prophets of Israel had all pointed to Christ. Everywhere that God appeared in the Scriptures was as a pre-existent Christ.

Christianity was now a religious system that was no longer ethnically Jewish, and no longer aligned with the dominant culture, but a unique system with elements from both.

The Christianization of the Roman Empire

Life unexpectedly changed for all Christians in 312 CE. In his goal of becoming the sole ruler of the Roman Empire, Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) clashed with another contender in the Western Empire, Maxentius. The night before the Battle at the Milvian Bridge in Rome, Constantine received a vision with either the sign of the cross or the first two letters of Christ's name, chi/rho, with the words en toutoi nika ("in this sign conquer") written beneath. Defeating Maxentius, Constantine credited the victory to the Christian god.

The Edict of Milan (313 CE) finally granted Christians the permission to assemble. Constantine’s conversion to Christianity did not make the Empire Christian overnight, but Christianity now had legal standing. Constantine favored the Christians by exempting the clergy from taxes, appointing Christians as magistrates, and providing funds for the building of churches.

During Diocletian's persecution, some Christian bishops had committed apostasy by sacrificing to the gods. The debate on whether the lapsed bishops should be forgiven split the churches, and they appealed to Constantine as a mediator. To promote the unity of the Empire, he ordered a policy of "forgive and forget" and became the official head of the Church as the supreme patron of Christianity. He adopted the views of the Church Fathers and utilized the same concept as when Rome persecuted Christians: anyone who disagreed with his Christianity was deemed a heretic and guilty of treason.

The Council of Nicaea

When the followers of Jesus began worshipping him as a god, Christians struggled with a problem that was related to their claim that they inherited Jewish monotheism. From the very beginning, Christians had worshipped Jesus as a god and had baptized "in the name of the Father and the son and the holy spirit" (Didache 7:5). Early in the 4th century, a presbyter in the church at Alexandria by the name of Arius proposed that if you believe that God created everything in the universe, then at some point, as creator, he must have created Christ. This demoted Christ as subordinate, a creature of God. Riots arose over this in Alexandria and in other cities. In 325 CE, Constantine called for a major conference to settle this issue and invited 217 bishops to the city of Nicaea.

After days of debate, the conference voted that God and Christ were identical as to essence (sharing the same ethereal substance), and they had existed from the very beginning of time. When God emanated the logos (as Christ), he became manifest in the earthly Jesus. With Christ identical to God, the Christian heritage of monotheism of traditional Judaism was retained, now defined as belief in one God. Until Christ returns, the Christian Emperor would stand in for him on earth. As the stand-in for Christ, portraits of Constantine and his successors have halos over their heads.

While he had all the bishops in attendance, Constantine had them create what became the Nicene Creed, another Christian innovation. (It is called a creed from the Latin of the first word "Credo" or "I believe"). In the ancient world, the concept of a creed did not exist because there was no central authority to dictate conformity. As both head of the state and the church, Constantine mandated what every Christian should believe so as not to fall into the sin of heresy.

Constantine ordered 50 copies of the gospels to be distributed, most likely determining the official recognition of what became the four canonical gospels. Some Christian communities had followed the Jewish lunar calendar for celebrating Easter, while others varied. Constantine set the official date as the way they did it in Rome: it would be honored on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox. He later selected December 25 as the birthday of Christ (Christmas), incorporating many of the traditions found in the Roman celebration of Saturnalia in December.

Not all the Bishops were content with the Nicene Creed. Over the next several centuries, several Councils met to debate details, and this would continue throughout the Middle Ages and beyond. Theodosius I (r. 347-395 CE) is remembered as a great champion of orthodoxy. He issued an edict in 381, which spelled the official end of native cults in the ancient world. Theodosius banned the Olympic Games (dedicated to the gods) in 396 CE, not to emerge again until 1896. All native temples and shrines were ordered destroyed or turned into churches. This is when Christians invented the term pagianoi ("pagans," equivalent to ignorant ones), a negative slur against those who had not yet converted.

Monasticism & the Cult of the Saints

Monasticism originated in Egypt in the mid-3rd century CE and eventually became a major institution in Catholic and Eastern Orthodox communities. Anthony of Egypt (251-356 CE), was the first to renounce the traditional conventions of life in this world, for one of isolation and complete devotion to God. He retired to a cave in the desert to spend his life in prayer. Soon, other men and women followed him to live as hermits in the desert. The recluses, deemed "Desert Fathers and Mothers" became models of piety and eventually gave rise to the monastic orders of the Middle Ages.

Christians borrowed the ancient ideas of Greek hero cults and the concept of patron/client relationships. Hero cults had been established by cities that claimed to have the tombs of the heroes. People made pilgrimages to these sites, petitioning the heroes (now with the gods) to mediate for them and provide benefits. Beginning in the 4th century CE, earlier martyrs' tombs, as a sacred intersection between heaven and earth, became the object of pilgrimage and Christians petitioned the dead martyr through hymns and prayers. The dead martyrs and monastics were now patron saints, and towns and cities that had a martyr's grave became famous sites of pilgrimage.

To remove the taint of idolatry in public buildings that were now churches, Christians began exhuming the bones of dead martyrs and moving them into the walls of the buildings. It was believed that these relics contained a special power to make the building a sacred space. The trade of relics (bones and items that touched earlier martyrs) became a phenomenon throughout the empire and remains important in the Catholic Church.

The Rise of the Institution of the Papacy

After the sack of Rome, 410 CE, by Alaric I, the king of the Visigoths, the fall of the Western Roman Empire began. In 450 CE, Attila the Hun invaded Italy, sacked several cities, and headed for Rome. Bishop Leo I (400-461 CE), also known as Leo the Great, is credited with negotiating with Attila to spare the city. As the bishop of Rome, he took on the secular responsibilities, which created the institution of the Papacy. Leo was granted the title 'Patriarch of the West', which included the first usage of the title 'Pope' for Leo. The word popa is derived from the Greek word for father. Validation for the power of the pope was drawn from the primacy of Peter, retroactively claiming Saint Peter as the first pope of Rome.