The sculpture of ancient Korea was dominated by Buddhist themes such as figurines and monumental statues of the Buddha and his followers, and large bronze bells for temples. Gilded-bronze was the most common material used by Korean sculptors, but they also used marble, stone, clay, iron and wood. Non-Buddhist sculpture includes masks, guardian figures for tombs, and carved poles, all of which were designed to ward off evil spirits. Initially influenced by Chinese art, Korean sculptors would go on to create their own unique style and themselves influence the sculpture of ancient Japan.

Three Kingdoms Sculpture

The earliest known sculpture from the peninsula is a small stone figurine of a nude female excavated near Busan which dates to the Neolithic period. At this time, pinched clay figures were also made but sculpture in any great quantity was not produced until the Three Kingdoms period (1st century BCE to 7th century CE).

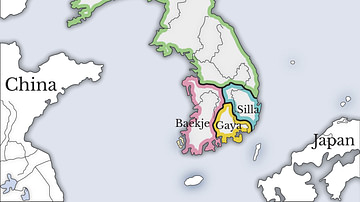

In all three kingdoms of Baekje (Paekche), Silla, and Goguryeo (Koguryo), which ruled the peninsula from 57 BCE to 668 CE, Buddhism was a huge influence on sculpture with the production of wooden and metal figures of the Buddha, Maitreya (the coming Buddha) and bodhisattvas, stone lanterns for temple sites, temple roof tiles with hideous faces to ward off evil spirits, and incense burners all being particularly popular. Baekje artists also sculpted cliff faces to represent the Buddha such as at Sosan.

This period saw the production of stelae depicting Buddha and his followers which were originally created in Baekje. Four examples from the Piamsa temple near Yongi are carved from soapstone and measure just under half a metre in height. They are probably from the Silla kingdom and carry high relief sculpture of Buddhist figures and musicians set against a mandorla background. One is mushroom-shaped and has a pagoda represented on the back side. All are currently in the National Museum of Korea, Seoul.

The most common form of Buddhist sculpture from this period is portable icons either of triad figures of the Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas or single bodhisattva figurines. These are made in bronze and gilt-bronze. The earliest known statue dates to 539 CE and displays the flaming mandorla around the Buddha's head which was typical of the art of the Northern Wei of China. The figure is also of note for the inscription on the back which indicates the great quantity of such figures made. It reads:

In the seventh year of Yonga, the year of Kimi, the head priest of the East Nangnang Temple of the Kingdom of Koguryo wishes to cast and distribute one thousand Buddhas, of which this is the twenty-ninth. (Kim, 110)

The Baekje kingdom provides the most outstanding example of a metal incense burner, the only survivor of its kind. Made from gilt-bronze, it stands 135 cm tall. The foot is in the form of a dragon and supports a mountain in the shape of an egg which is decorated with heavenly beings and clouds. The whole is topped by a lid decorated with a phoenix.

Baekje metalworkers and sculptors passed on their skills and ideas to Japan in the mid-6th century CE when there were close relations between the two territories. From this time, Korean figure sculpture becomes more independent from Chinese influence and faces are noticeably more Korean in representation and less-rounded, helping to distinguish Buddhist sculpture from the two cultures from now on.

Unified Silla Sculpture

The Unified Silla Kingdom (668- 935 CE) saw a new art form develop, that of making large bronze-cast bells (pomjong) which were struck from the side using a suspended wooden beam. Housed in their own pavilions, they were used in Buddhist temples to announce services. The largest example is from Pandok-sa, also known as the Emille Bell, which was cast in 771 CE to honour King Seongdeok. 3.3 metres tall and over 2.2 metres in diameter, it is decorated with lotus flowers and heavenly beings with a suspension loop in the form of a dragon. Weighing almost 19 tons, the bell is now on display in the Gyeongju National Museum.

Perhaps the finest of all Korean figure sculpture is to be found in the Seokguram near the Bulguksa Temple on Mt. Toham, Gyeongju. The artificial grotto was constructed between 751 and 774 CE and contains a magnificent granite seated Buddha. 3.45 metres high, he sits cross-legged on a large circular pedestal or throne, itself 1.6 metres high. The grotto is decorated with a total of 41 figure sculptures carved in high relief which depict various figures from Buddhism. They are regarded as amongst the finest ever produced in Korea.

Other monumental stone figures include a group of four outside Gyeongju. Carved on each side of a granite boulder, according to a legend recounted in the Samguk yusa, King Gyeongdeok (r. 742-765 CE) heard a voice from under the ground and on excavating at the spot he discovered the figures. A temple was also built at the site, the Kulpulsa or 'Temple of the Excavation of the Buddhas.'

Some large figure sculptures were made using cast iron with parts made separately and then assembled and painted or covered in plaster. It is still small-scale sculpture, though, that provides the finest examples of craftsmanship. Figurines of the seated Maitreya display finely modelled facial features, realistic body proportions, languorous postures (usually one leg crossed over the other), and deep folds in the figure's robes. Figures of the Buddha of Medicine (Bhaisajyaguru) and Vairocana Buddha, with his distinctive gesture of the fingers of the right hand holding the index finger of the left, were also popular. The former figures possibly gained popularity following an extended period of bad harvests and rampant banditry in the 9th century CE. Again, although iron and stone were commonly used, the material of choice for the finest pieces was bronze which was then gilded with gold leaf and a mercury amalgam. When heated the mercury evaporated, and the figure was then polished.

Folk art of the period provides some interesting sculptural forms. The changsung were tall thin posts topped by a human face. Set in the ground in pairs at village entrances, they were carved from stone or wood and thought to act as guardians. Sometimes the wooden versions were carved from an entire tree trunk, and the roots were left so that when placed in the ground upside down they looked like the hair belonging to the brightly painted demon face. A common superstition was that if anyone removed a changsung, then a man would die in the village. Food offerings were hung from them and chestnuts sometimes buried at the foot. Changsung were also fertility symbols prayed to by women and sometimes even placed in front of Buddhist temples; the oldest dates to 759 CE. Another popular form of folk sculpture which combined a fertility and guardian function was harubang. These were stone sculptures of human figures of all types which were stood outside tombs to ward off evil spirits. A third type of guardian pole was sottae, which were poles topped by a carved bird. Finally, a popular wooden sculpture was kirogi. These were wooden ducks given as a replacement to the earlier tradition at weddings where the bridegroom gave a goose to the bride's mother to guarantee his fidelity.

Goryeo Sculpture

Goryeo ruled Korea from 918 CE to 1392 CE, and its sculptors used a variety of mediums including marble, stone, terracotta (lacquered or gilded), and metal. Figures of Buddha as Maitreya continued to be popular, and some are massive such as the 17.4-metre-high one at Paju and the 18.4-metre-tall figure at the Gwanchoksa temple in Nonsan, which were both carved out of natural boulders in the 11th century CE. These statues have only the bare essentials of detail and are much more abstract than metal figures. Many of them wear unique tall hats, and this may represent a link with shamanism, long-practised in ancient Korea. Large-scale metal statues were still being made too, as in the Silla kingdom, such as the 'Gwangju Buddha,' which stands 2.88 m tall.

Another area of metalwork was the production of bells for Buddhist temples. Smaller than the giant bells made by the earlier Unified Silla kingdom, Goryeo bells can still be up to 1.7 metres tall and were cast in bronze and decorated with dragons and heavenly figures, amongst others. One unique feature is the lotus medallion cast at the point where the bell was struck. Handbells, temple gongs, incense burners, and vases were also cast in bronze and sometimes embellished with very fine silver and gold inlay.

Standing figures of soldiers or officials were commonly placed in pairs outside tombs, as per the China model. Wooden masks are another example of the non-Buddhist sculpture of the period. Created for traditional mask dances, they have deep-set eyes and long straight noses, which suggest a Central Asian influence. Masks had long been produced in Korea and were worn by shamans or used to ward off evil spirits in tombs and houses. In the second half of the period, sculptures are mostly small-scale and made with gilt-bronze and begin to show an influence of the Yuan artists who arrived with the Mongol occupation of Korea from the 13th century CE.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.